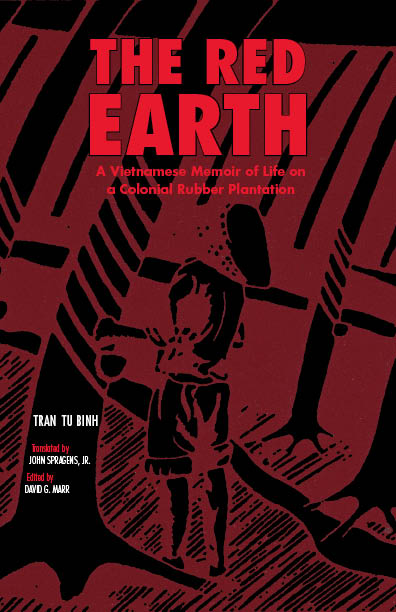

The Red Earth

Ohio University Research in International Studies

This series of publications on Africa, Latin America, Southeast Asia, and Global and Comparative Studies is designed to present significant research, translation, and opinion to area specialists and to a wide community of persons interested in world affairs. The editors seek manuscripts of quality on any subject and can usually make a decision regarding publication within three months of receipt of the original work. Production methods generally permit a work to appear within one year of acceptance. The editors work closely with authors to produce high-quality books. The series appears in a paperback format and is distributed worldwide. For more information, consult the Ohio University Press website, ohioswallow.com.

Books in the Ohio University Research in International Studies series are published by Ohio University Press in association with the Center for International Studies. The views expressed in individual volumes are those of the authors and should not be considered to represent the policies or beliefs of the Center for International Studies, Ohio University Press, or Ohio University.

The Red Earth is the fifth volume in the Translation Series of the Southeast Asia Translations Project Group. It is published in cooperation with the Center for International Studies, Ohio University, as Number in the Centers Research in International Studies, Southeast Asia Series.

The Red Earth

A Vietnamese Memoir of Life on a Colonial Rubber Plantation

by Tran Tu Binh

as told to Ha An

translated by John Spragens, Jr.

edited and introduced by David G. Marr

Ohio University Center in International Studies

Research in International Studies

Center for Southeast Asian Studies

Southeast Asia Series Number 66

Ohio University Press

Athens

Introduction

Tran Tu Binh was born May 1907 in an all-Catholic village in Ha-nam Province in the Red River delta of northern Vietnam. His father sustained the family by collecting and selling manure, perhaps the lowliest occupation in the village. His mother managed nevertheless to scrape together enough money to enroll Tran Tu Binh at a seminary, where he disappointed both of them in 1926 by being expelled for publicly mourning the death of Phan Chu Trinh, a prominent Vietnamese scholar-patriot. At that moment, without yet knowing it, Tran Tu Binh joined the ranks of the young intelligentsia, a group destined to play a critical role in modern Vietnamese history.

As narrated with piquancy and verve in this autobiography, Tran Tu Binh spent the next year as an itinerant Bible teacher, then signed up to labor on a rubber plantation in the distant red-earth region of southern Vietnam [Cochinchina]. Although he doesnt say so, this was surely another severe blow to the family. After all, even without any school diploma, Tran Tu Binh could have found a respectable job as village clerk, landlords agent, or shopkeeper simply because he knew how to speak and read French as well as Vietnamese. Instead he was determined to break away, to seek adventure, to test his physical and spiritual powers on totally unfamiliar terrain. He was also vaguely familiar with the Leninist concept of proletarianiza tion, whereby young intellectuals immersed themselves in a work ing-class environment in order to engineer eventually the overthrow of both foreign imperialists and native landlords.

Even before boarding the French ship Dorier that was to take him south, Tran Tu Binh became embroiled in a confrontation with plantation recruiting agents who had defrauded hundreds of his illiterate fellow workers. Because the agents feared that many contract workers might simply pack up and return home, some satisfaction was obtained; however, the atmosphere became more ominous the further they traveled. When the ship docked in Saigon, workers were driven ashore like cattle and a spokesman was badly beaten for daring to complain. After being trucked to a tropical forest location kilometers north of Saigon, Tran Tu Binh found himself in truly appalling physical and psychological circumstances.

Phu Rieng was one of about twenty-five French rubber plantations that stretched in a three-hundred-kilometer band from the South China Sea to the Mekong River in Cambodia. From before World War I the colonial government had allocated huge blocks of forest land to metropolitan corporations; from 1920 on, large amounts of capital became available to construct roads, nurture rubber seedlings, clear land, and plant saplings. Unlike the British in Malaya, who imported Indian or Chinese nationals to develop rubber estates, the French decided to use indigenous labor. However, they soon discovered that the proto-Indonesian tribespeople who normally wandered this region were quite unsuited to plantation work. Ethnic Vietnamese who resided in and around Saigon, although they might be lured on a seasonal basis, preferred not to sign longer-term contracts. Besides, they were close enough to home to walk away if conditions proved intolerable. These facts led French rubber companies, with colonial government encouragement and assistance, to focus increasingly on recruiting contract laborers from the heavily populated Red River delta provinces far to the north. From a mere , contract laborers on southern rubber plantations in 1922 , the number increased ten times to , in 1930 . Tran Tu Binh was one of the , who arrived in

alone.

Todays reader will perhaps be skeptical of Tran Tu Binhs hell-on-earth description of Phu Rieng. Admittedly, he employs poetic license on occasion. For example, one finds it hard to believe that so many husbands died of humiliation and heartbreak after their wives had been raped by plantation overseers. Nor does it seem likely that all pregnancies at Phu Rieng resulted in stillbirths. On the other hand, many of Tran Tu Binhs grim assertions are confirmed in confidential reports that colonial administrators forwarded to Paris, and which are now available for study in the Archives Nationales de France (Section Outre-Mer). For example, the minister of colonies is told that percent of Phu Rieng workers died in 1927 , probably a conservative figure, since the plantation supervisory staff had reason to cover up some losses. Then, too, Tran Tu Binhs characterization of Triair, the plantation director, as particularly brutal is corroborated in a report of the governor general to Paris.Overall, Trans account of plantation life may be assessed as exaggerated in tone, yet essentially reliable in substance.

One theme pervades The Red Earth: the existence of a bitter test of wills between exploiter and exploited. We see it first in Tran Tu Binhs confrontation with the Canadian priest, Father Quy, which culminates in a bit of Jesuit-like rhetorical jousting in a Hanoi prison eighteen years later. We see it again in the authors argument with the captain of the Dorier en route from Haiphong to Saigon. Most important, we are witness to the ruthless, persistent efforts of the Phu Rieng supervisory staff to tear down the psychological defenses of Vietnamese workers in order better to control them. For at least one year these tacticsakin to those of slave masters, prison workers, and drill sergeants since time immemorialenjoy considerable success. Workers are clearly disoriented and demoralized. Gradually, however, some workers recover internal poise, improvise protective tactics, organize quietly, and plan countermeasures. Ironically, they are assisted by Triairs less brutal successor, Vasser, who allows them to form a variety of sporting, cultural, and religious groups.