The British on the Costa del Sol

The British in Spain achieved notoriety during the 1980s. As a group they were stereotyped as being made up of exiled criminals, drunken hooligans and inward-looking pensioners unwelcome colonisers reconstructing their own insular little England. The British on the Costa del Sol presents a more complex picture.

In this first book-length ethnography of the British expatriate community, Karen OReilly draws on history, social geography, tourism studies and theories of ethnicity and community to frame detailed interviews with British migrants themselves. What emerges is a rich account of who migrates, their reasons for migration and the day to day realities of expatriate life. While Britons migrating to Spain have not integrated into their host communities, neither have they colonised swathes of the Spanish coast. The author presents instead a marginal group occupying a liminal space between two countries and two cultures.

The British on the Costa del Sol is a lively and accessible account of an under-researched transnational community, and will appeal to social anthropologists and sociologists as well as to the general reader.

Karen OReilly is Lecturer in Sociology at the University of Aberdeen.

The British on the Costa del Sol

Transnational identities and local communities

Karen OReilly

First published 2000

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxfordshire OX14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

2000 Karen OReilly

Typeset in Bembo by

Florence Production Ltd, Stoodleigh, Devon

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

OReilly, Karen

The British on the Costa del Sol: transnational identities and local communities/Karen OReilly

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. BritishSpainCosta del SolHistory20th century. 2. Great BritainEmigration and immigrationHistory20th century. 3. Costa del Sol (Spain)Emigration and immigrationhistroy20th century. 4. ImmigrantsSpainCosta del SolHistory20th century. I. Title. DP302.C84 074 2000

ISBN 1841420484 (hbk)

ISBN 1841420476 (pbk)

For Trevor, for everything

Contents

Acknowledgements

Roger Goodman, of the University of Oxford, remains by far the greatest influence on this book. I owe him a huge debt of gratitude for teaching me anthropology, for training me in the arts of academia, and for guiding, cajoling, supporting, advising, humouring and never bullying me through the three and a half years of my PhD. He has provided continuity and strength. Above all, he enabled me to write the thesis, and now the book, which I wanted to write, and I do not hold him responsible for any of its failings.

I am proud to acknowledge the help, encouragement and influence of the following professionals: Rob Stones, for taking me seriously in the first place, Richard Wilson, for keeping me going in the field with his vigilant, challenging and warm correspondence, and Elizabeth Frances, for keeping my feet on the ground during the writing-up. But, nothing would have been achieved without friends. I especially want to thank Helen Hannick, Pauline Lane, Jackie Turton, Maggie (its all part of the process) French, Ted Benton, Sean Field, David Forfar, Steve Hussey and David Lee for providing challenging debates, for reading and commenting on drafts, for emotional support, and for laughter. Special thanks to Carolyn Dodd for putting up with me and for putting me up so many times.

I would like to thank the Sociology department at Essex for their administrative support and help while I did the PhD, and the department at Aberdeen for giving me a lectureship, which meant I could write the book. The ESRC are to be thanked for their financial support in the form of a studentship award.

Numerous British migrants have generously allowed me to investigate their lives and to tell their stories. I cannot thank them sufficiently. They are too numerous to mention but, though I have used pseudonyms in order to respect privacy, they may be able to recognise themselves in the pages of this book. I hope I have done them justice. Special thanks are due to John and Anne Symonds, Cecil Roberts, Charles Betty, Hatti (A. Haitia), Joan Hunt, Keith and Maria Osborne, and to Kerrie for her friendship.

Finally, many, many thanks are due to my partner, Trevor, my daughters, Laura and Kelly, and the other children in my family, Justin, Jemma and Jasie. Thank you for bearing with me, and thank you for being you. Here is the result of our hard work and your patience.

Karen OReilly

University of Aberdeen

January 2000

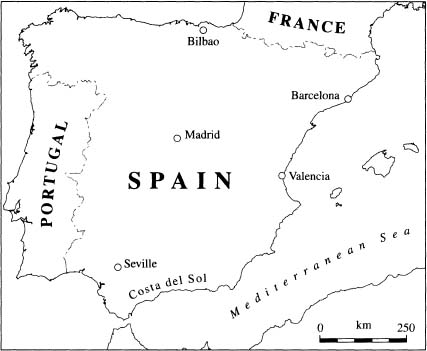

Map 1 The Spanish mainland

Source: Reay-Smith 1980: 19

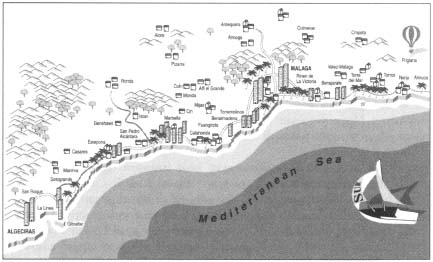

Map 2 Malaga province

Source: Sur in English

1 Introduction

The Brits in Spain

When I first met my partner, Trevor, in 1988, he had a dream to move to Spain. He had been to the Costa del Sol on several occasions for holidays, once working there for a month, and had fallen in love with it. He took me to the area in which he hoped to settle, the Fuengirola area, and part of me could understand his desire. I too fell in love with the mountain views, Spanish fiestas and food, the warm winter sun, the holiday atmosphere, and the friendly Britons who had already settled there. After a few visits I wanted to move there too, but I had many fears and apprehensions. What would we live on? What would I find to replace my love of education and research? Would I miss my extended family and friends in England? I worried about my daughters education: if they went to Spanish school would they cope well enough to be able to compete in the Spanish employment market? Would they be able to transfer their skills to England at a later date? Would they be happy? However, it was not an option we could take seriously for several years since we had neither the capital nor employment in Spain to fund such a move. I began to wonder how the many Britons who lived there had overcome such obstacles.

My interest in Britons in Spain thus activated, my intellect was also challenged by reports of the way in which Britons were apparently living in Spain; reports that suggested that many were not happy there, that they had made mistakes in the planning of their settlement abroad and now wished to return to Britain; reports of elderly people feeling lost and alone; reports that Britons showed no interest in the Spanish way of life nor in learning the language. I had been to Fuengirola enough times to have met several expatriate Britons and to know them to be extremely happy with their lives in Spain, and to be in love with Spain and the Spanish people. I was aware of no loneliness, ill health or unhappiness, and of no problems related to lack of integration or to isolation. I began to wonder what was going on, that reports could vary so much from what appeared to be the truth.