First published in Great Britain in 2017 by

Policy Press University of Bristol 1-9 Old Park Hill Bristol BS2 8BB UK Tel +44 (0)117 954 5940 e-mail

North American office: Policy Press c/o The University of Chicago Press 1427 East 60th Street Chicago, IL 60637, USA t: +1 773 702 7700 f: +1 773-702-9756 e:

Policy Press 2017

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book has been requested

ISBN 978-1-4473-2410-2 paperback

ISBN 978-1-4473-2409-6 hardcover

ISBN 978-1-4473-2413-3 ePub

ISBN 978-1-4473-2414-0 Mobi

ISBN 978-1-4473-2412-6 ePdf

The right of Val Gillies, Rosalind Edwards and Nicola Horsley to be identified as authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved: no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission of Policy Press.

The statements and opinions contained within this publication are solely those of the author and not of the University of Bristol or Policy Press. The University of Bristol and Policy Press disclaim responsibility for any injury to persons or property resulting from any material published in this publication.

Policy Press works to counter discrimination on grounds of gender, race, disability, age and sexuality.

Cover design by Policy Press

Front cover image: Getty images

Readers Guide

This book has been optimised for PDA.

Tables may have been presented to accommodate this devices limitations.

Image presentation is limited by this devices limitations.

The politics of early intervention and evidence

Introduction

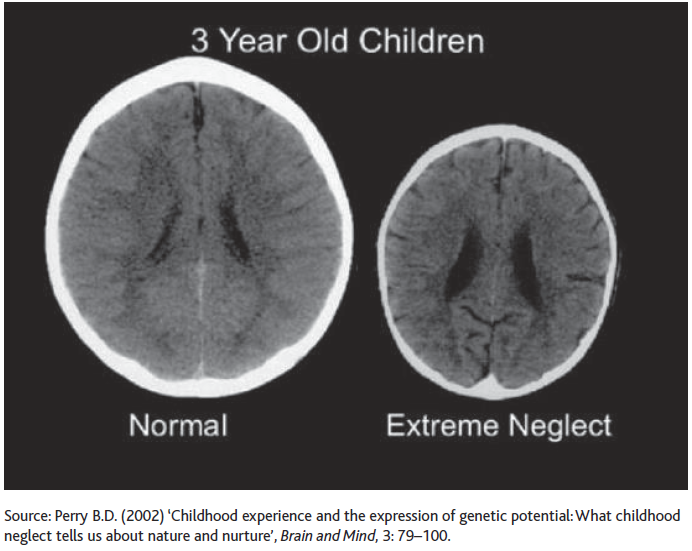

In 2002 a cross-sectional picture of two brains placed side by side was published in an article by Bruce Perry, founder of the ChildTrauma Academy in Houston Texas, an independent agency promoting a Neurosequential Model for working with at-risk children (see Figure 1.1). The image purported to show MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scans of the structure of the brains of two 3-year-old children. One was the brain of a child who had what was referred to as a normal development, and the other was a rather smaller, shrivelled brain with worrying black holes (Allen, 2011a: 16) indicating enlarged ventricles or cortical atrophy from a child labelled as subject to extreme neglect.

Figure 1.1: Perry brain image

This brain scans picture has become iconic, a key motif in political and thinktank reports concerning childrens upbringing and outcomes from across the spectrum. It provides a graphic visual image for assertions that poor parenting causes lasting damage to babies and young childrens brain development. In two influential policy reports we read that:

A key finding is that babies are born with 25 per cent of their brains developed, and then there is a rapid period of development so that by the age of 3 their brains are 80 per cent developed. In that period, neglect, the wrong type of parenting and other adverse experiences can have a profound effect on how children are emotionally wired. This will deeply influence their future responses to events and their ability to empathise with other people. (Allen, 2011a: xiii)

From birth to age 18 months, connections in the brain are created at a rate of one million per second! The earliest experiences shape a babys brain development and have a lifelong impact on that babys mental and emotional health. (Leadsom et al, 2013: 5)

The Perry image feels like solid, objective evidence of the formative importance of attentive mothering for babies brain development and the need to intervene early to ensure that childrens brains are not damaged by substandard parenting. A Childrens Centre supervisor told us during one of the research interviews that we conducted for the project that underpins this book, that the picture of the brains justifies robust interventions: But I think just brain science, that photograph shows to me so much, and it gives me so much passion in what Im doing and give more definite this is the right thing to be doing (Childrens Centre interview 2).

The evidence captured in the MRI scans image thus provides a potent moral call for intervention to take place in the early window of opportunity in a childs life, before it is too late and their brains are hard-wired for failure through deficient parenting (variously, up to the age of 3 or the age of 18 months depending on the report). This is a message that has become an internationally accepted policy and practice truth. Child development reports by the World Health Organization (Irwin et al, 2007) and UNICEF (Bellamy, 2000; Lake and Chan, 2014), and early years policy and service provision in the UK and internationally (Macvarish et al, 2014; see also Bruer, 1999; Wilson, 2002;Wall, 2010; Ramaekers and Suissa, 2012) are now characterised by an emphasis on early intervention in the belief that pregnancy and the earliest years of life are most important for development. It has become the orthodoxy in a whole range of professional practice fields; a professional association review helpfully provides a list of many of the relevant services: family support, parenting support, health visiting, nurseries, early education, day and child care, the interface between early years and health and housing.

The idea is to pre-empt instead of reacting to social, educational and behaviour problems using evidence-based interventions. Rather than the spotlight alighting on the unequal material and social conditions in which children live and doing something about them, it is focused on parents and how they rear their children. These are ideas that blame poor mothers for making their own and their childrens deprived bed and lying in it. In the process, it presents them as not quite the human beings that we are, biologically and culturally. In an address to a conference on early intervention attended by practitioners, Graham Allen MP (Labour), then Chair of the Early Intervention Foundation, invoked the notion that disadvantaged mothers, and indeed generations of families, are somehow not like us: