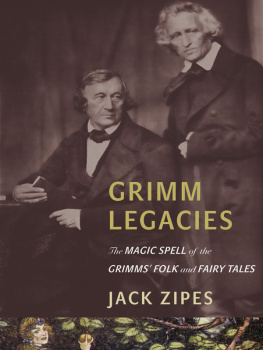

Clever Maids, Fearless Jacks, and a Cat

Fairy Tales from a Living Oral Tradition

E DITED BY

Anita Best

Martin Lovelace

Pauline Greenhill

I LLUSTRATED BY

Graham Blair

U TAH S TATE U NIVERSITY P RESS

Logan

2019 by University Press of Colorado

Published by Utah State University Press

An imprint of University Press of Colorado

245 Century Circle, Suite 202

Louisville, Colorado 80027

All rights reserved

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of University Presses.

The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State University, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Metropolitan State University of Denver, Regis University, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, University of Wyoming, Utah State University, and Western Colorado University.

ISBN: 978-1-60732-919-0 (paperback)

ISBN: 978-1-60732-920-6 (ebook)

https://doi.org/10.7330/9781607329206

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Lannon, Alice, 19272013, storyteller. | Power, Pius, 19151993, storyteller. | Best, Anita, 1948 editor. | Lovelace, Martin J., editor. | Greenhill, Pauline, editor.

Title: Clever maids, fearless Jacks, and a cat : fairy tales from a living oral tradition / edited by Anita Best, Martin Lovelace, Pauline Greenhill ; illustrated by Graham Blair.

Description: Logan : Utah State University Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019020517 | ISBN 9781607329190 (pbk.) | ISBN 9781607329206 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Fairy talesNewfoundland and LabradorSpecimens. | TalesNewfoundland and LabradorSpecimens. | FolkloreNewfoundland and LabradorHistory. | Oral traditionNewfoundland and Labrador. | Spoken word poetry.

Classification: LCC GR113.5.N54 C55 2018 | DDC 398.209718dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019020517

The University Press of Colorado gratefully acknowledges the generous support of the University of Winnipeg and Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador toward the publication of this book.

Cover illustrations by Graham Blair. Background illustration Bplanet/Shutterstock.

Contents

W E THANK THE FOLKS AT U TAH S TATE U NIVERSITY Press and the University of Colorado Press, especially Rachael Levay, Darrin Pratt, Kylie Haggen, Beth Svinarich, Dan Pratt, and Laura Furney, for bearing with us during the process, and for locating such discerning and enthusiastic external readers, whose comments and suggestions we sincerely welcomed and happily incorporated. Indispensable funding came from the University of Winnipeg Research Office (special thanks to Jennifer Cleary); Memorial University of Newfoundland (special thanks to Holly Everett); Research Manitoba; and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada Partnership Development Grant 890-2013-17, Fairy Tale Cultures and Media Today. The Memorial University of Newfoundland Folklore and Language Archive staff were most helpful, especially archivist Pauline Cox and archival assistant Nicole Penney, who came through with a couple of last-minute saves. Our research assistants were Alexandria van Dyck, Alina Sergachov, Baden Gaeke-Franz, Brittany Roberts, Emma Tennier-Stuart, Lydia Bringerud, Noah Morritt, and Shamus MacDonald. Delf Maria Hohmanns photographs of the tellers beautifully evoke them. We thank copyeditor Robin DuBlanc for taking on the ethnopoetics, our Canadian spelling and the rest, and Kristy Stewart for the excellent index. For various forms of feedback, encouragement, and assistance, we gratefully acknowledge Rex Brown, Diane Goldstein, John Junson, Kate Power, Patricia Rose, Barbara Rieti, Jack Zipes, and members of the Power family living in Southeast Bight.

F AIRY TALES ARE AMONG THE OLDEST ORAL STORIES whose history can be traced; in the West this documentation stretches back to classical antiquity. Their themes inspire writers, visual artists, and filmmakers; in the twenty-first century few media creators fail to find in them something relevant (see Greenhill et al. 2018). Yet we dont know their original makers. Certainly the tales werent invented by the Brothers Grimm, Charles Perrault, or Giovanni Francesco Straparola, to list only a few contributors to the canon. Such authors, with different purposes, created their texts using characters, plots, and relationships from sources that sometimes were already written, but commonly were encountered in oral storytelling.

Its become fashionable among some academics to disparage the idea of an oral tradition as a construct of Romanticismthat nothing of such enduring worth could have been created by the nonliterate and uneducated. The stories in this book may or may not sway opinion in this debate (Lovelace 2018). But here we present two makers of tales: thoughtful, creative, attentive to narrative in a way that few non-storytellers are. One grew up in a literate family; the other had little opportunity to learn from books. Nothing can be known about the crazy, drunken old hag (Walsh 1994, 113) who told the story of Cupid and Psyche in Apuleius, The Golden Ass (ca. 160 CE). But in the following pages we introduce Alice Lannon, who told her own version of that old womans tale, among others, and Pius Power, whose many long and complex stories show just what artistry is possible without the written word. (We call them Pius and Alice, as we authors refer to ourselves also by our given names.)

The Newfoundland into which Philip Pius Power (19121993) and Alice (McCarthy) Lannon (19272013) were born was a very different place than it is now. Then a self-governing colony of Britain, a Dominion like Canada or Australia, it would lose its autonomy under the Commission of Government imposed from London in 1934 as a condition of rescue from bankruptcy caused by the Great Depression and, ironically, the debt Newfoundland had incurred to pay for its part in defense of the British Empire in World War I. In 1948, by a slender margin, Newfoundland voted to become a province of Canada and entered Confederation in the following year. The population was then 313,000 on the island, spread over 9,656 square kilometers, with a further 5,200 in the larger but more sparsely populated Labrador portion. The 2016 census showed the total population of the province of Newfoundland and Labrador as just under 520,000.

In the Second World War Newfoundland became the fortress from which convoys sailed across the North Atlantic to Britain carrying food and war material. American forces established bases at Gander, Stephenville, St. Johns, and Argentia. In the process they raised local wages to a previously unseen level, putting cash into the hands of men and women who had received very little actual money when they labored under the truck system, in which fishers were outfitted by the local merchant and turned in their catch to him in return for food and other supplies. An enlighteningand horrifyingaccount of destitution among Newfoundlands people in the 1930s, and corruption among the powerful, can be found in White Tie and Decorations, the letters of Lady Hope Simpson and her husband Sir John, who was a member of the Commission of Government (Neary 1996).

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of University Presses.

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of University Presses.