Copyright 2022 by Bloomberg L.P.

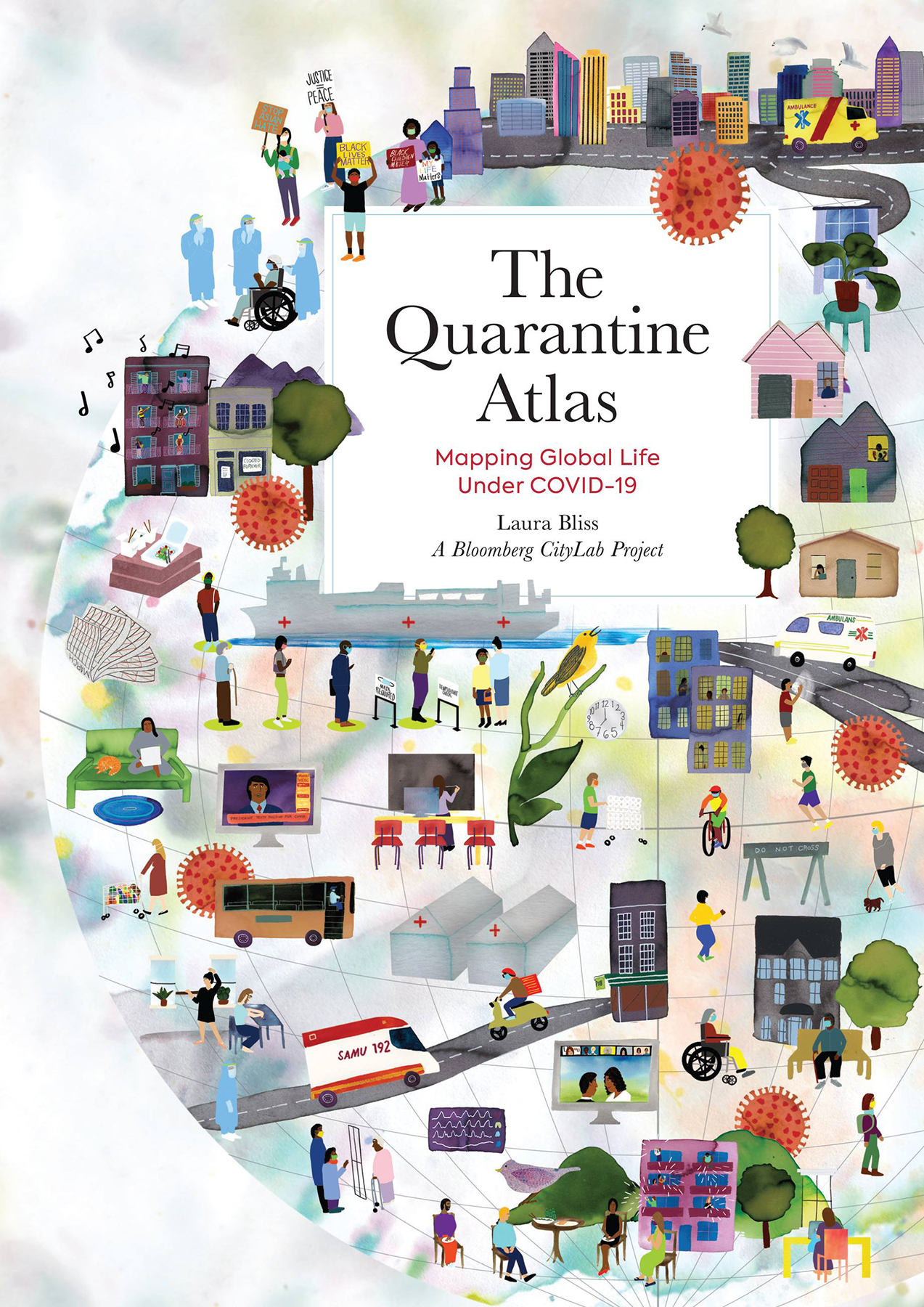

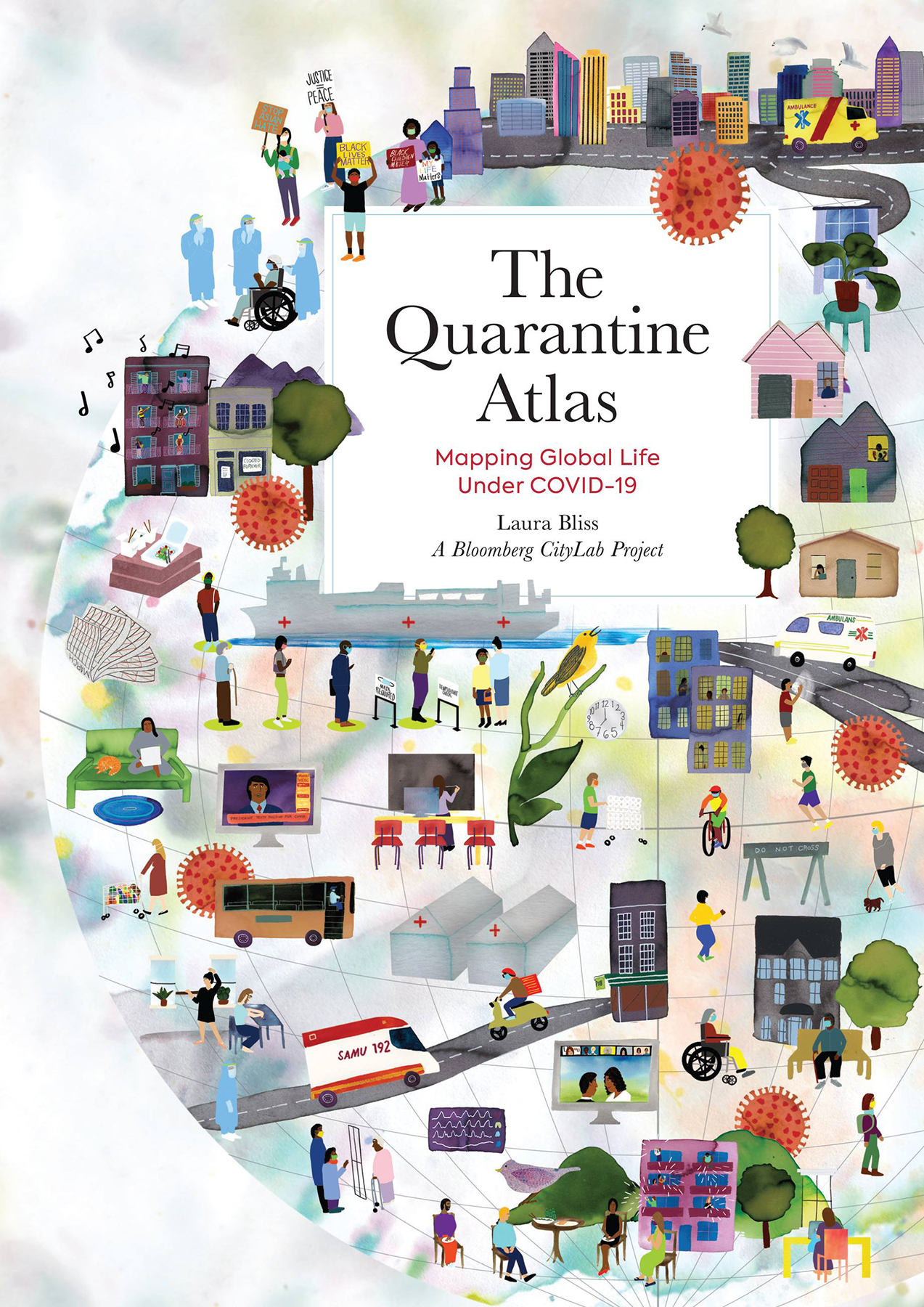

Front cover, back cover, and interior illustrations copyright 2022 by Jennifer Maravillas

: 1937 Thomas Bros. Oakland/Berkeley map with HOLC data

United States Geological Survey. The National Map. Reston, Va: U.S. Department of the Interior. June 26, 2021.

OpenStreetMap contributors

Cover copyright 2022 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10104

www.hachettebookgroup.com

www.blackdogandleventhal.com

First Edition: April 2022

Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers is an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.HachetteSpeakersBureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

ISBNs: 978-0-7624-7812-5 (hardcover); 978-0-7624-7813-2 (ebook)

E3-20220215-JV-NF-ORI

O n a warm afternoon in the early months of the pandemic, my daughter dressed up like a spider and danced in the backyard. Her modern dance class had gone virtual, and the recital would be on video. She put on a black leotard with felt spider arms and set up an iPad to film her routine. My wife and I werent allowed to watch this, so we masked up, leashed up the dog, and headed out on another aimless walk.

The routine of these circuits around the neighborhood had already worn a familiar groove into our heads; only the dog managed to find fresh joy in the experience every day. Wed taken to cutting through strange alleys and wandering farther from the house, longing to see something new. In time we found something: In another backyard, several blocks from ours, there was another little girl dancing around in a different homemade spider costume.

This strange scene turned out to not be that strange, once we figured it out; here, apparently, was another member of my daughters dance class. They were dancing together, but apart. But it still lingers as one of those moments that seemed to capture the uncanniness of life under lockdown. After months of few opportunities to explore beyond the immediate surroundings, our senses became highly attuned to minute changes in the environmenta fresh bumper sticker on a parked car, new yard signs, the status of area home-improvement projects, an unusually fat squirrel. On Nextdoor, the neighbor-centric social media platform, other homebound residents appeared to be similarly starved for novelty. Amid complaints about leaf blower noise and sketchy visitors, posters announced, Weird cloud! and asked, Whats this snake? We marveled at mundanity.

A trope of the early pandemic was that Generation Xers like myself, by dint of our deep childhood exposure to post-apocalyptic pop culture and facility with TV-saturated self-isolation, were made for this shit, as New Yorks Will Leitch wrote in March 2020. We believed that watching The Day After and The Andromeda Strain as children equipped our cohort with the emotional tools to endure quarantines, field hospitals, and whatever other horrors the pandemic was likely to serve up; their plots taught us that institutions like governments and modern science were likely to fail in their efforts to overcome the threat. Plus, while Boomers and Millennials balked at the deprivations of lockdowns, we were too freighted with family responsibilities to want to go out. The time to stock up and hunker down had come, as we always knew it would, and we were prepared for what awaited.

In truth, we were not remotely made for this shit, and whatever generational advantage we may have initially possessed evaporated as the months ground on and the long-term miseries of parenting and caregiving under COVID-ized conditions gnawed away at our sanity. The coronavirus crisis also failed to live up to the promise it initially held to my generation of cynics, in that it did not provide much in the way of satisfying entertainment. The pandemic was a kind of anti-spectacle, visible only as things that were not there and distractions we couldnt pursue. Instead of city-swallowing tidal waves and flaming skyscrapers, we got empty buses and closed bars, uncrowded highways, and heaps of takeout containers. Among those who could stay home and stay healthy, at least, the human suffering of COVID-19 in overwhelmed emergency rooms and nursing homes might as well have been happening on another planet.

Thats why the images in this book are such valuable documents, in that they allow us to clearly see a phenomenon that was, to many of us, largely invisible: the precise shape and texture of lives broken and reassembled by a catastrophe whose dimensions remained just beyond our field of vision. These hand-drawn depictions of personal worlds collapsed to the neighborhood scale are full of the kind of mundane marvels that landmarked the lockdown lives of others. And they offer something that spiking infection graphs and more traditional depictions of the pandemics toll donta sense that we were all, in various and very different ways, engaged in an epic feat of shared survival.

Were all in this together. The pandemic was just weeks old when this oft-expressed sentiment was exposed as risibly false, so vast was the gulf between how people of different means and persuasions experienced the disease and its disruptions. The waves of outbreaks and lockdowns that rippled on for months splintered the species into often-warring camps marked by geography, ideology, age, and affluence.

Still, its worth trying to recapture the basic truth of the statement. Though it didnt feel like it, we became witnesses to a once-in-a-lifetime astonishment. A pandemic marching remorselessly across the planet, the great cities of the world stilled overnight, scientists scrambling to combat a viral invaderthis was the stuff of the disaster movies Gen X watched as kids. But in real life, it was a crisis that often played out not as a global blockbuster but as a series of drawing-room dramas in homes and hospital hallways and apartments and backyards, each one isolated from the others, unseeable and unknowable.

It will be the task of the generation that truly was born for this shityoung people who came of age in the pandemicto tell the truest stories about this crisis, and to prepare for the future ones. Though they were less vulnerable to the virus itself, teens and tweens like my own saw the disease claim great chunks of their childhoods, marking their adult years in ways that the grown-ups cant imagine. For some, the lost year of the pandemic is leaving educational gaps and emotional scars; others have adapted and even thrived, as kids raised amid disaster and disruption often do. If were lucky, COVID quarantine could end up being just one more weird thing in the long string of inexplicable incidents that is childhood. When they become adults, theyll share something amazing with billions of survivors their age, and maybe theyll be able to explain to the rest of us what it all meant.

Next page