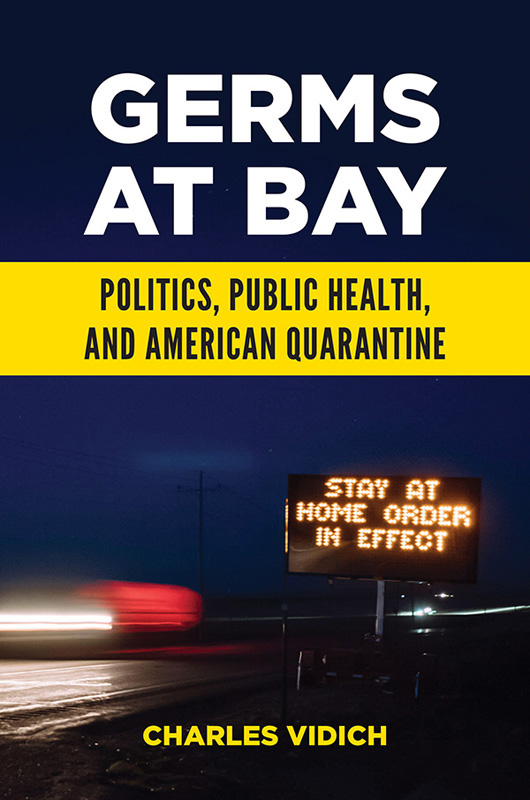

Germs at Bay

Copyright 2021 by Charles Vidich

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Vidich, Charles, author.

Title: Germs at bay : politics, public health, and American quarantine / Charles Vidich.

Description: Santa Barbara : ABC-CLIO, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020034372 (print) | LCCN 2020034373 (ebook) | ISBN 9781440878336 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781440878343 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: QuarantineUnited StatesHistory. | Public healthUnited States.

Classification: LCC RA665 .V53 2021 (print) | LCC RA665 (ebook) | DDC 614.4/60973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020034372

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020034373

ISBN: 978-1-4408-7833-6 (print)

978-1-4408-7834-3 (ebook)

25 24 23 22 21 1 2 3 4 5

This book is also available as an eBook.

Praeger

An Imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC

ABC-CLIO, LLC

147 Castilian Drive

Santa Barbara, California 93117

www.abc-clio.com

This book is printed on acid-free paper

Manufactured in the United States of America

To my wife, Clare, and my three sons, Jamie, David, and Paul

Contents

This book would not have happened without a series of chance encounters that opened me to consider quarantine as a critical tool for the twenty-first century. I am indebted to James Bromberg, MD, JD, MPH, for our endless days of studying quarantine at the Harvard School of Public Health (HSPH). Without his friendship and camaraderie, I would not have undertaken this book. Indeed, in my own experience, James Bromberg is one of the few attorney-physicians who fully grasps the importance of quarantine in the modern world.

In 2001, I had been working on the governments response to the anthrax crisis in the postal system when I met Dr. Don Milton at the anthrax conference held at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, Georgia. Through a series of discussions and subsequent meetings, I took a one-year limited leave from my normal duties in the government to pursue my interests in bioterrorism and infectious disease. Through Don Milton I met Drs. Jennifer Leaning and Arnold Howitt, who would later become my faculty advisers on a special project to investigate the application of quarantine to nineteenth-century communicable diseases. Laura Lynn Taylor, Jim Bromberg, and I spent a semester investigating the application of quarantine in New Orleans, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Boston. Our research was taking place as the Asian SARS epidemic was emerging, which gave added impetus to our efforts.

After completing my degree program at the HSPH, I suggested an extension of my work to complete a more comprehensive investigation of the 1872 Boston smallpox epidemic. This epidemic had never been studied in detail, and yet it offered an enormous number of remarkable lessons for public health officials concerned with the twenty-first-century application of quarantine. HSPH accepted my request to pursue this scholarly investigation under the guidance of Jennifer Leaning. As a visiting scientist at HSPH, I have been deeply indebted to Jennifer Leaning for sponsoring my research and suggesting ways of framing the quarantine project. She is nothing short of one of the most remarkable persons I have ever metequally at ease in the world of medical history as she is in the world of real-time emergency response to medical disasters throughout the world. To have had this opportunity was certainly fortuitous and was enabled by my chance meeting with Don Milton.

I am deeply indebted to Rebecca Orfaly Cadigan and Anson Wright, both of whom spent considerable time and energy reviewing earlier versions of this manuscript and providing editorial and substantive suggestions. In the world of quarantine research, there are very few who have invested the energy and time in understanding these issues as well as Anson Wright and Rebecca Orfaly Cadigan. This book would not have been possible without their insightful comments.

I am also indebted to John Freitas for reviewing an early version of the manuscript and providing insightful comments about the history of Boston as only a true Bostonian could do. The discussion of island quarantine would not be as complete without his comments. Two other people who opened my awareness of Boston Harbor were Peter Tropeano, captain of Boston Waterbus Services, Inc., and Darryl Forgione of the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Conservation. Mr. Tropeano provided marine transportation to numerous Boston Harbor islands during the summer of 2005, and Mr. Forgione provided access to Gallops Island at a time when it was off limits to the public. Without their support it would not have been possible to connect the dots between nineteenth-century harbor geography and the landscape of today.

The amount of research required to complete this manuscript was formidable. There is no one library or research facility where all of the quarantine records for Boston or federal quarantine programs can be found. Indeed, over forty different libraries and research facilities were extensively consulted to prepare this history. Harvards Widener, Countway, Lamont, Pusey, Littauer, Law, and Houghton Libraries contained extensive records of the early history of Boston and the epidemics of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The Countway Library of Medicines Rare Books collection was invaluable for tracing the nineteenth-century history of quarantine and the dual role of Harvards medical professors as consulting physicians to the city of Boston. I am indebted to Jack Eckert, reference librarian, and Peter Rawson, archivist, and their colleagues for supporting my research. In addition, Joseph Garver, reference librarian, and his colleagues at the Nathan Marsh Pusey Library assisted with access to the historic maps of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Boston. These ancient maps were invaluable in depicting harbor channels, quarantine grounds, and island features that explained the geographic constraints faced by port physicians, harbor masters, and commanders when negotiating their way from Bostons docks to its quarantine islands.

The Boston Public Library staff was of tremendous help in the completion of this book, particularly Henry Scannell, curator of microtext and newspapers. Mr. Scannell spent countless hours helping to identify smallpox cases and incidents of quarantine in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Boston. The microtext files for the Boston Globe, the Advertiser, and the Boston Herald provided detailed coverage of the 1872 smallpox epidemic that was critical to the completion of this book.

The quarantine history of Boston cannot be told without access to federal records. In this regard, the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) staff in College Park, Maryland, provided exceptional support with the identification and retrieval of Public Health Service records from the early twentieth century. David Pfeiffer went above and beyond the normal responsibilities of his job and pulled many Boston Quarantine Station files for my review during evening hours when I had the time available to scour the extensive federal records for Gallops Island.