Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the Print Version

ANDREA CHAPELA

THE VISIBLE UNSEEN

Translated from the Spanish byKelsi Vanada

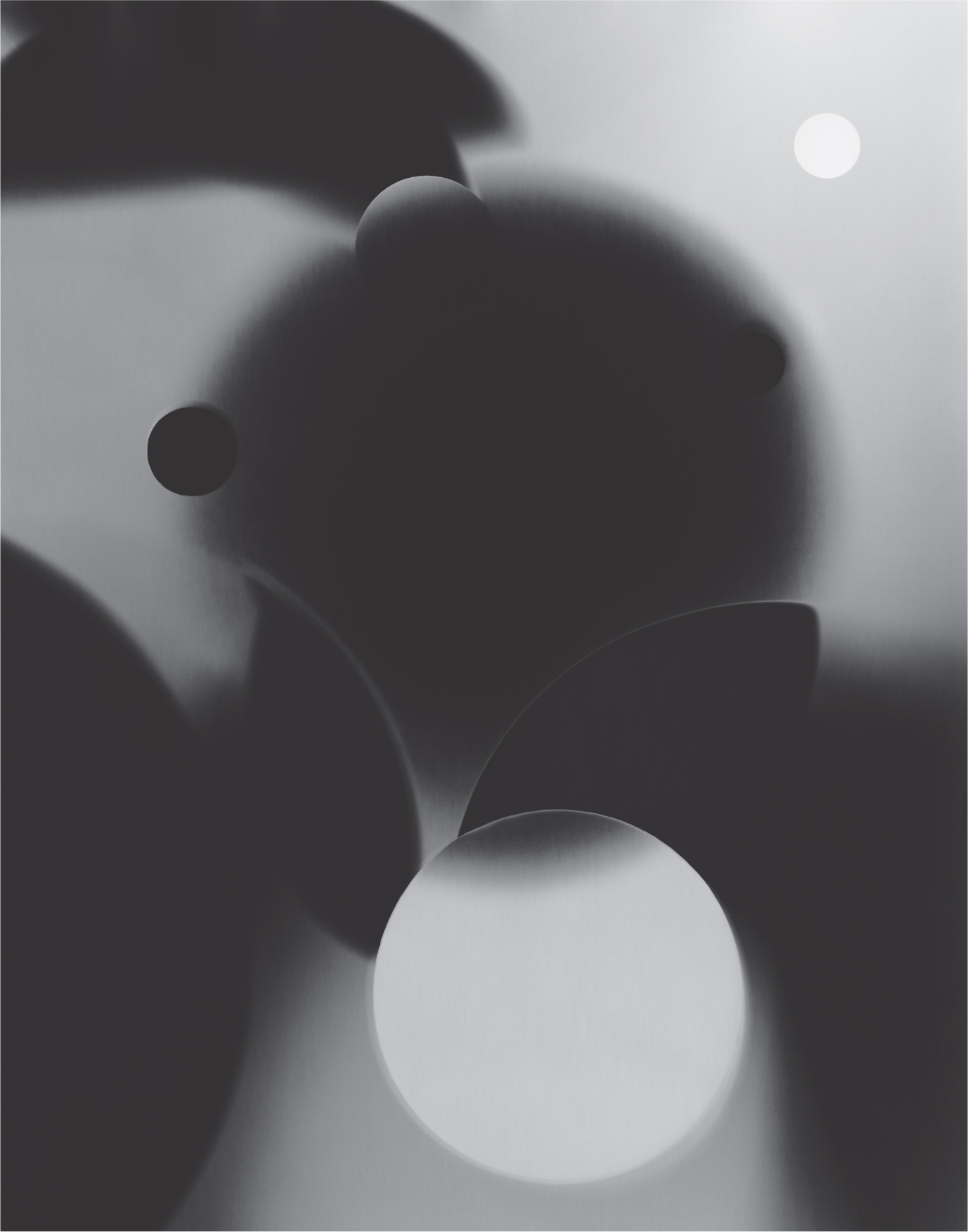

Artwork by Fabiola Menchelli

RESTLESS BOOKS

BROOKLYN, NEW YORK

Copyright 2019 Andrea Chapela

c/o Indent Literary Agency

www.indentagency.com

Translation copyright 2022 Kelsi Vanada

Prismatic compass 2012 Fabiola Menchelli

Motto, Ocular, Yoru, and Eclipse 2021 Fabiola Menchelli

fabiolamenchelli.com

First published as Grados de miopa by Tierra Adentro, Mexico City, 2019

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted without the prior written permission of the publisher.

First Restless Books hardcover edition October 2022

Hardcover ISBN: 9781632063526

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022937665

Cover design by Emily Comfort

Text design by Tetragon

Cover image by Fabiola Menchelli

This book is made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Kathy Hochul and the New York State Legislature.

Printed in United States

13579108642

Restless Books, Inc.

232 3rd Street, Suite A101

Brooklyn, NY 11215

www.restlessbooks.org

For my parents, the Mathematician and the Physicist

CONTENTS

Human beings have a curious spirit and poor eyesight. If we had better eyesight, we could see whether or not stars are suns which light their worlds, and if we were less curious, we wouldnt care. The trouble is, we want to know more than we can see.

BERNARD LE BOVIER DE FONTENELLE

THE ACT OF SEEING

I DONT REMEMBER how the discussion beganbut I know it took place in January, when Chicago is covered in snow and its impossible to be outside. From Iowa, I cross five hours of barren countryside in harsh weather to visit my friend A, who is getting her PhD there. We plan to eat dinner at the home of some mutual friends: two writers and a photographer. I think the discussion starts during dessert, when theres still a bottle of wine left. Someone (maybe me) makes a comment about some scientific topic, or about the vegan meal, or about As thesis. Someone else (one of the artists) decides to play devils advocate, wondering how science can be perceived as reliable (that is, true) if theories change over time and often contradict each other. A and I try to explain why precisely that is the marvel of science, what separates it from dogma. The details of the discussion arent important, and Ive forgotten many of the arguments. Suffice it to say that A and I are on one side, defending science, and the artists are on the other, casting doubt. More than anything, I remember my frustration. It was as if we spoke different languages and were incapable of communicating with each other. I tell all this to arrive at one particular moment: Im searching for an irrefutable example, so I grab a knife from the table and drop it on the floor to illustrate gravity and Newtons laws. But I get all muddled up and fail to convince anyone. A interrupts me and explains what I just said over again. Im uncomfortable. I know my lack of scientific rigor annoys her. For the first time, I feel that in choosing writing, Im distancing myself from the world of science that has surrounded me since childhood.

Miroslav Holub, Czech poet and immunologist, wrote: The sciences and poetry do not share words, they polarize them. As soon as I read that phrase, I wanted to negate it. Contradict it. It comes back to me when I set out to write a series of experimentslets call them essaysto look at science through the lens of poetry and observe the result of that polarization: liminal language.

I met A in my first year of chemistry at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. Our friendship was always grounded in our similarities: we both studied pure chemistry and were fascinated by quantum chemistry. We both had scientific parents. We both read science fiction and fantasy. We had both gone to a public university after studying at private secondary schools. She played piano and composed music; I wrote novels. We were connected by our penchant for competing interestson the one hand, science, and on the other, artas well as our doubts about what to choose as a future profession. After four years, A started a PhD program in chemistry in Illinois, and I moved to Iowa to study creative writing.

What is the name for the silence between the lightning bolt and the thunder? wonders the Asturian poet Xuan Bello. I go to a poetry reading hes part of, and weeks later, Im still turning this idea around in my mind. How can that moment be described? A lightning bolt is an electrical discharge that ionizes the air molecules. It cuts through the atmosphere in a matter of milliseconds, heating the gas and expanding it. The hot air increases in volume until it crashes into the surrounding cooler air currents. The air contracts. A rapid movement, violent. The silence between the lightning bolt and the thunder is the crack of a shock wave. No one word names the full process, but we are all familiar with the feeling of expectation. We hold our breath. The air expands, contracts. Rumbles.

Before I sit down to write, I seek out models to guide me, a process thats a holdover from my scientific education. I trust the clarity definitions can provide at the outset, and I feel its easier to understand something if its named. When I come across the category of lyric essay, I cling to it. The genre gives me the form even before the foundation is settled and helps me organize my thoughts. In looking at science from a poetic point of view, Im trying to encounter it afresh by making it unfamiliar.

Sometimes the processnot of writing a book, but of living itreveals what were looking for. Thinking of these three essays as one unit sends me back to my feeling of separation from science, to my friendship with A, to one poets question and the words of another. Im trying to braid all these threads together not to track the books progress, but my own process as I create it. Lyric essay is an experimental genre because its based on experience. And writing from experience means allowing the world to break into the text. This prologue is another experiment. Generated at the end, to be read at the beginning, it becomes a statement of intent.

I think back to As interruption. It was like a lightning bolt, a kind of catalyst that made me realize how far Id strayed from the concepts and language of science. From the ionization and expansion that followed, I gained clarity. I want to get close to science again, look at it with new eyes. Thats why I must begin with this confession: to me, science is beautiful, and when I write, I want to explore that beauty.

Perhaps the pages that follow are simply an attempt to cling to all the parts of myself and never let them go.

THE ACT OF SEEING THROUGH

Object of Study: Glass