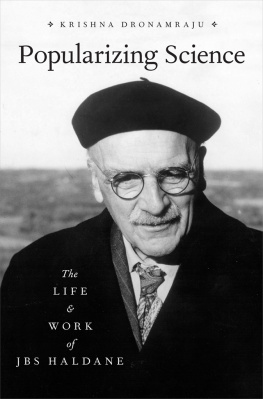

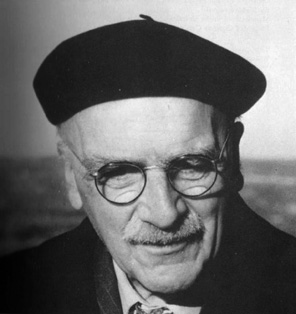

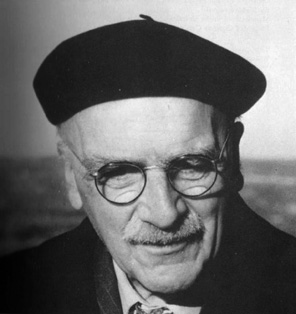

WHAT I REQUIRE FROM LIFE

J.B.S. Haldane, 1963, near lake Winona, in Madison,

Wisconsin by Dr Klaus Patau, Department of Medical Genetics,

University of Wisconsin

WHAT I REQUIRE FROM LIFE

Writings on Science and Life

from J. B. S. Haldane

EDITED BY

KRISHNA DRONAMRAJU

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship,

and education by publishing worldwide in

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press

in the UK and in certain other countries

Published in the United States

by Oxford University Press Inc., New York

Krishna R. Dronamraju 2009

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

Database right Oxford University Press (maker)

First published 2009

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press,

or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate

reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction

outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department,

Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover

and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Data available

Typeset by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India

Printed in Great Britain

on acid-free paper by

Clays Ltd., St Ives pic

ISBN 9780199237708

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

by Sir Arthur C. Clarke, CBE

J. B. S. Haldane was perhaps the most brilliant science popularizer of his generation. Starting in 1923 with Daedalus; or Science and the Future, he must have delighted and instructed millions of readers. Unlike his equally famous contemporaries, Jeans and Eddington, he covered a vast range of subjects. Biology, astronomy, physiology, military affairs, mathematics, theology, philosophy, literature, politicshe tackled them all. He also wrote a workmanlike novella, The Gold Makers, and a charming tale for children, My Friend Mr. Leakey.

Haldanes scores of essays may still be read with great profit. They appeared in such varied places as Harpers Magazine, the Saturday Evening Post, the Strand Magazine, The Spectator, the Daily Expressand, of course, the Daily Worker.

Haldane wrote a series of articles for the Daily Worker from 1937 to 1949, at a time when he subscribed to the ideals of socialism and communism (which, in the real spirit of open-mindedness, he changed later). This was followed by regular contributions to Indian newspapers during the last few years of his life (195764). Written in his usual lucid style, their breadth and depth of coverage indicate that he was truly a multi-disciplinary scientistan effective bridge between the two cultures.

It is a pity that these essays are not as widely known today as they ought to be. So I am very glad that one of Haldanes former students and long-standing associates, Professor Krishna Dronamraju, is bringing out this collection. Krishna has previously edited or compiled a number of publications based on the work of his mentor. We can derive fresh insights from this collection of works by one of the greatest science communicators of our times.

I was first attracted to Haldanes writings by the element of extrapolation they contained. He obviously was sympathetic to science fiction and astronautics; indeed, this paragraph was contained in his very first book, Daedalus:

I should have liked, had time allowed, to have added my quota to the speculations which have been made with regard to inter-planetary communication. Whether this is possible I can form no conjecture; that it will be attempted, I have no doubt whatever.

It was through space flight that I made my first encounter with Haldane. In 1951, as Chairman of the British Interplanetary Society, I invited him to give our organization a paper on the biological aspects of space flight. Although it was arranged at very short notice, the lecture was a great success. He dealt with three problems: how humans would live in spaceships, how they would live on other planets, and what sort of life they might find there. At that timesome six years before the Space Age dawnedthese were not subjects with which many reputable scientists cared to be associated.

Haldanes 1951 paper still contains some interesting ideas. He must have been one of the first to point out the dangers of solar flares and to suggest that space voyages should be made during periods of minimum solar activity. And, with his tongue firmly in his cheek, he suggested that we should take seriously the hypothesis that life has a supernatural originfrom which he concluded that, as there are 400,000 species of beetles on this planet, but only 8,000 species of higher animal forms, the Creator, if he exists, has a special preference for beetles, and so we might be more likely to meet them than any other type of animal on a planet that would support life.

The second time our paths crossed was in November 1960, by which time both Haldane and I had settled down in the East (him in Bhubaneswar, eastern India, and myself in Colombo, Ceylon).

The Ceylon Association for the Advancement of Science invited Haldane to address its annual meeting, and he arrived with Krishna Dronamraju and another colleague. Over the next few days, I had the stimulating experience of showing them around Colombo, and having them over at my house.

One evening after dinner, we screened the movie Beneath the Seas of Ceylon, which my diving partner Mike Wilson and I had recently madethe first time the Indian Oceans undersea wonders were captured on film. I can still remember how Haldane watched it with such delight, showing the sense of wonder that is the hallmark of the great scientist.

More details of this second encounter are found in my essay Haldane and Space, which I wrote at Krishnas invitation for the excellent memorial volume he edited, Haldane and Modern Biology. It is also included in my own collection of essays, Report on Planet Three and Other Speculations.

Haldane and I never met again, but we sustained a correspondence. His letters, usually handwritten and often running into a thousand words, were so full of ideas as his agile mind jumped from one subject to another that they were both good fun and hard reading.

In 1962, shortly after I had won the UNESCO Kalinga Prize for the popularization of science, I received an invitation to stay with the Haldanes. It opened with this rather ambiguous compliment:

Next page