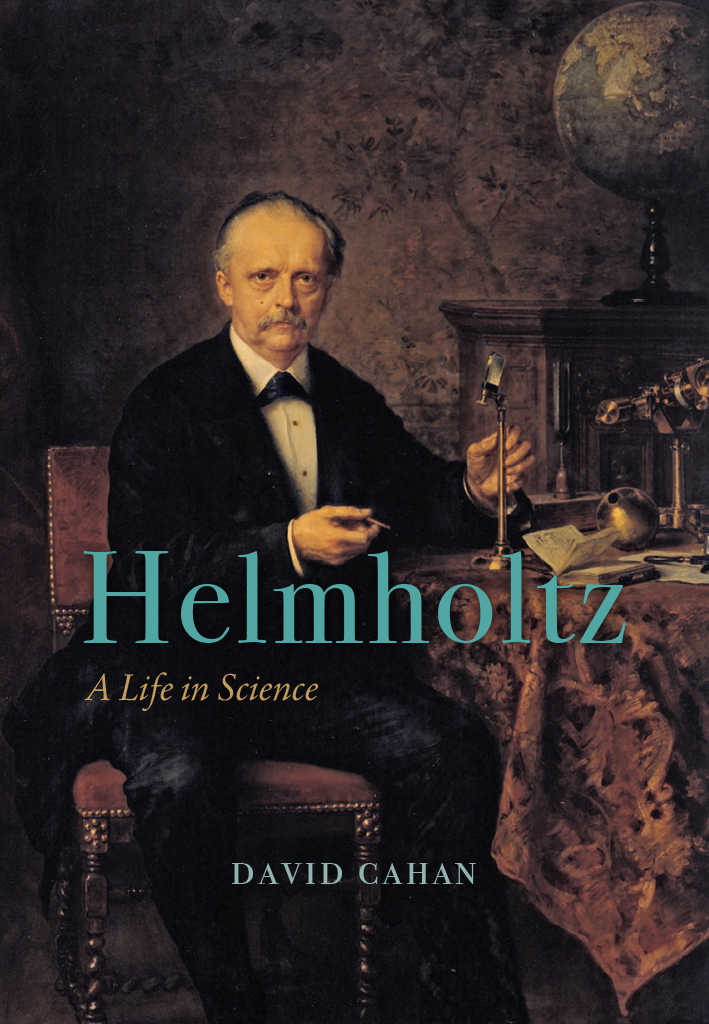

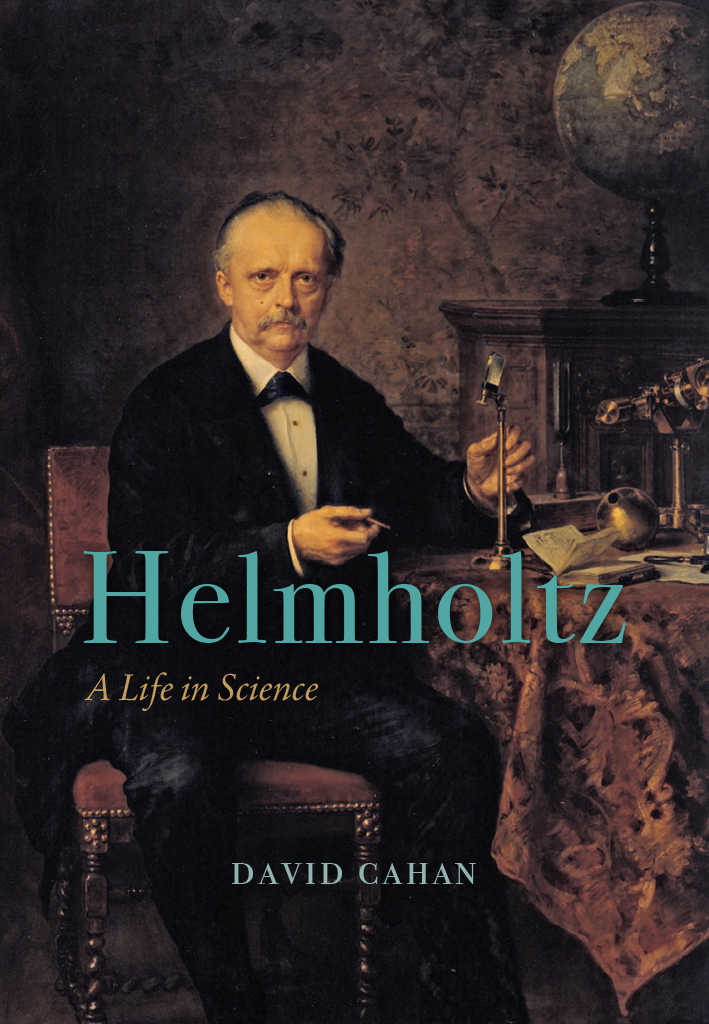

Helmholtz

Helmholtz

A Life in Science

David Cahan

The University of Chicago Press Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2018 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2018

Printed in the United States of America

27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-48114-2 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-54916-3 (e-book)

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226549163.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Cahan, David, author.

Title: Helmholtz : a life in science / David Cahan.

Description: Chicago : The University of Chicago Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018003417 | ISBN 9780226481142 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226549163 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Helmholtz, Hermann von, 18211894. | ScientistsGermanyBiography.

Classification: LCC Q143.H5 C34 2018 | DDC 509.2 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018003417

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

To the memory of my father and mother,

Haskell and Sylvia Cahan

The wise man

Seeks the trusted law in chances horrifying wonders,

Seeks the resting pole in phenomenas flight.

Schiller, The Walk, 1795

Contents

Though it has long been essential for scholarly use, it is an uncritical assessment, embellishing if not heroizing its subject; indeed, it helped to create a mythological figure of the man, making him an icon and an idol.

The present biography of Helmholtz, by contrast, seeks to be a comprehensive, balanced, and thematic study of Helmholtzs life and science, setting both deeply in their time and place and attempting to understand the influences upon Helmholtz and his upon his age. It endeavors to take the full measure of the man, doing so critically in the multiple contexts in which he lived and worked. It utilizes all of Helmholtzs published and known unpublished writings: his scientific, philosophical, and popular articles and books; his extant correspondence (both published and unpublished); all known pertinent official documents concerning his academic career; third-party correspondence; and the excellent, extensive secondary literature on or about Helmholtz. It utilizes many previously unknown or scarcely known sources, as well as older, better-known sources, to illuminate Helmholtzs life, work, and career in a fresh way. It seeks neither to lionize nor to demonize him but aims to provide an authoritative, critical account of his life and work as these developed in their historical context, that of an emerging and evolving scientific community.

: : :

The intellectual leitmotifs and the driving forces of Helmholtzs creative scientific, philosophical, and aesthetic life were threefold: a passion to unify the sciences, both as individual disciplines and collectively; vigilant epistemological attention to the sources and methods of knowledge; and acute appreciation of the complementary and mutually stimulating roles of the arts for the sciences and vice versa. These leitmotifs and passionswhich constitute the theme of this biographybobbed in and out of his life and work, and they took different forms on different occasions. They expressed themselves as his drive to unify the different branches of physics (at first by means of the law of conservation of energy, then later in his career by means of the principle of least action); as his drive to find a common foundation for physics and physiology; and as his desire to bring some unity to all the natural sciences. He sought laws in science.

Helmholtz also deeply respected and analyzed the methods of the Geisteswissenschaften: the human sciences, that is, the humanities and, to speak somewhat anachronistically, the social sciences. They, too, found a placesubordinate though it may have beenin his vision of the wholeness and unity of knowledge. To be sure, since the human sciences inherently involved human psychology, he did not believe they could produce lawsan all-important point for him, as we shall see. To the intellectual and psychological driving force of his career must be added his passion for and scientific analysis of music and painting. In dealing with their respective forms of tone and color, he showed how a combination of acoustics and optics, and the closely associated physiological acoustics and optics, could illuminate understanding of the fine arts. For Helmholtz, the artsnot only music and painting, but also literature and theaterwere at once a source of relaxation from his demanding scientific work and a source of inspiration for that work. He thought that artists, in their own and different ways, were, like scientists, seeking to express natures laws. He was a Renaissance man.

Helmholtz was driven in no small part, this biography argues, by a psychological need to find or create laws in science. It was a need that originated in childhood as a means of compensating for what he later described as the shortcomings of his deficient memory. By adulthood it had evolved into the centerpiece of his philosophy of science. In his view, law brought understanding of and mastery over nature. Along with Schiller, he believed that the wise man/seeks the trusted law. These lines concerning laws encapsulated in a striking, poetic

Helmholtz was an intellectual risk-taker in his search for laws; he sought after far more from scientific investigation than merely new factual data. As a young scientist, he hoped to find the causessometimes he called them the forcesthat supposedly lay behind laws, and thus he hoped ultimately to provide an objective picture of the natural world, one that would somehow link together the different fields of natural science. Ultimately, he modified these aims. In 1891 he wrote: To discover the causal connections of phenomena has guided me throughout my life. Indeed, as this biography shows, there were strong connections between Helmholtzs physiology and parts of his physics, between his physiology and his development of non-Euclidean geometry, between his physics and his geometry, between his physics and his chemical thermodynamics, and between his physics and his meteorology, not to mention, more broadly, the implications of scientific laws and other findings for several other fields (medicine, experimental psychology, philosophy, music, and painting). Human sight and sound, and bodily heat, could be understood in no small part by understanding the physical and physiological laws that they obeyed. In this quest he demonstrated a perhaps unmatched, and certainly uncanny, ability to synthesize ideas, concepts, theories, and results from different fields of science.

By the 1860s or so, Helmholtz had come to favor a less demanding, and perhaps less philosophical goal for scientific laws or theories, a goal recognizing that perhaps all a scientist could ever realistically hope for was to articulate limited laws (and theories) on the basis of known phenomena. A world picture (Weltbild) ultimately eluded him, and with this, as with everything else in life, he learned to come to terms. He was a scientific genius, but he never forgot that theories must always be tied to empirical reality. Still, to the end of his life, he believed that the unity of the sciences implied the unity of all knowledge, and hence of the producers of knowledgethe scientific community as a whole. This in turn, he further believed, meant increased civilization for all of humanity. Science, in his vision, meant a civilizing power for everyone.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).