Modernism, Science, and Technology

NEW MODERNISMS SERIES

Bloomsburys New Modernisms series introduces, explores, and extends the major topics and debates at the forefront of contemporary Modernist Studies.

Surveying new engagements with such topics as race, sexuality, technology and material culture and supported with authoritative further reading guides to the key works in contemporary scholarship, these books are essential guides for serious students and scholars of Modernism.

Published Titles

Modernism: Evolution of an Idea Sean Latham and Gayle Rogers

Modernism in a Global Context Peter J. Kalliney

Modernisms Print Cultures Faye Hammill and Mark Hussey

Forthcoming Titles

Modernism, War, and Violence Marina MacKay

Modernism and the Law Robert Spoo

The Environments of Modernism Alison Lacivita

For Laura, Devin, and Ciara

Modernism, Science, and Technology

Mark S. Morrisson

Bloomsbury Academic

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Contents

Bringing together the diverse and seemingly disparate threads of scholarship on modernism, science, and technology into a recognizable pattern, useful to students new to the field and scholars with some familiarity, is a project I had long wished to undertake. But it took the confluence of two remarkably persuasive forces to make it realizable: an enthusiastic invitation to contribute such a volume to the exciting New Modernisms Series at Bloomsbury, and a sabbatical in the middle of my term as head of a large English department. For the former, I thank Sean Latham, Gayle Rogers, and David Avital, whose generous encouragement and welcome advice made the new series the ideal venue in which to publish the book. For the latter, I am grateful to the College of the Liberal Arts and Penn State University for the precious research leave that allowed me to read and write, and read some more.

I thank the Tate for generous permission to reproduce Umberto Boccionis Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, and Chris Sutherns for his gracious assistance; ARS and the Philadelphia Museum of Art for permission to reproduce Marcel Duchamps The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even ( The Large Glass ); and the Krller-Mller Museum for permission to reproduce Fernand Lgers Nudes in the Forest.

In addition to David Avital, I thank the Bloomsbury editorial and production team, including Mark Richardson, James Tupper, and Grishma Fredric at Deanta, for bringing this project into print with welcome speed and courtesy, and I am grateful to Ryan McGinnis for his expert work on the index. Finally, I must thank my children, Devin and Ciara, for reminding me daily of the pleasures of the present even as I immersed myself in the fascinations of the past, and my wife, Laura Reed-Morrisson, who expertly commented on every page of this book and inspired me when I needed it most.

Make it new, prescribed Ezra Poundthe modernist poet, impresario, political lightning rod, contrarian, coiner of phrases, and launcher of movements. Modernists and avant-gardists of the early twentieth century exceled at bold statements heralding a brave new now. In 1924, Virginia Woolf famously observed that on or about December, 1910, human character changed, and five years later, Eugene Jolas proclaimed that the revolution in the English language is an accomplished fact. Moreover, this reconfigured present of modernism often hinted at an alluringor frighteningfuture that was already in the process of coming into the world, an ontological eruption. The Great War and other violent upheavals of the period could render those invocations simultaneously exhilarating and terrifying, even apocalyptic. William Butler Yeats, in The Second Coming, powerfully captured this tone: what rough beast, its hour come round at last, / Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born.

As the war drew to a close, four empires had collapsed, and the old aristocracies had lost much of their privilege. Future wars, totalitarianism, social, cultural, economic, political, and religious tumult, and the postcolonial world of later decades were visible on the horizon. Scholars have focused on modernisms emergence in the context of such globally significant events, and rightly so. An age of empire and the long nineteenth century, to use Eric Hobsbawms phrases, were ending. Yet some of these dynamics looked quite different across the Atlantic, where America was rising as a world power, more confidently signaling its own imperial ambitions and industrial and technological modernization.

In England and the United States, experiences of loss and vulnerability in a rapidly changing world were balanced by palpable excitement about a future in which the imaginations wildest flights of fancy might be realizablefor good or perhaps for ill. Whether causing apocalyptic dread or inspiring futuristic excitement, this modernization was technological and scientific. As this volume will show, many of the developments that fueled a growing modernist self-consciousness were precisely these rapidly paced technological and scientific changes. Science had achieved a formidable cognitive authority across the nineteenth century. By the twentieth, it seemed to augur swift, perhaps even limitless, progress in knowledge and technology. While many people began to see science and technology as the greatest agents of transformation, some began to doubt that these changes were necessarily uniform, continuous, progressive, or even necessarily beneficial. The vocabulary of progress, improvement, advancement, growth, and prosperity was a legacy of the Victorian period, but the dizzying pace and nature of change in the early twentieth century caused some to question the inherited narratives of progress. It was not just the new scientific developments but the fact of flux, the unsettling nature of fundamental change itself, that defined modernist science and modernist culture.

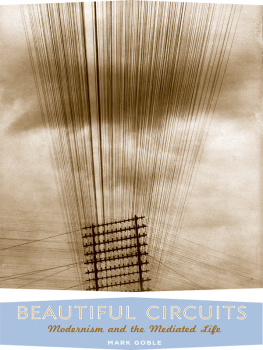

Alex Goody contends that technology was the dominating episteme of the twentieth century. What the twentieth century reveals about technology, Goody argues, is its profound fusion with the human; as the century progressed it became impossible to maintain an absolute distinction between the organic expressions of human nature and the technological processes, forms and devices which recorded and communicated those expressions as culture (1). Hints of that revelation were already present as the century began. Few modernists could be accused of neo-Luddism. But they understood and even created their technological and scientific culture in many different ways. Italian Futurism, often seen as the defining European avant-garde arts movement of the early twentieth century, offers a useful starting point for our inquiry into the modernist science and technology at the epicenter of the culture of modernism.

Like a garish advertising poster whose newly liberated typography had broken its mooring on the line, Italian Futurist F. T. Marinettis visually bold artists book Zang Tumb Tumb (1914) declared: No poetry before ours / with our wireless imagination words / in freedom longggGGG live FUTURISM fi- / nally finally finally finally / finally / FINALLY / Poetry being BORN (Correction, 57). Simultaneously sound poem and concrete poem avant la lettre, Zang Tumb Tumb imagines the dynamism of words visually scattered and even freed from the page not only through the voice, but also, above all, through technology. Words could be spread out across foldout pages through the technologies of industrial typography. Or they could be freed from print itself, and even from the spatial limitations of human vocalization: the electromagnetic waves of telegraphy could propagate them across space wirelessly. Paradoxically, to liberate the imagination from all boundaries required fusing it with technology.