ON THE

SENSATIONS OF TONE

AS A PHYSIOLOGICAL BASIS FOR THE

THEORY OF MUSIC

HERMANN L. F. HELMHOLTZ

The Second English Edition, Translated, thoroughly Revised and Corrected, rendered conformal to the Fourth (and last) German Edition of 1877, with numerous additional Notes and a New additional Appendix bringing down information to 1885, and especially adapted to the use of Music Students by

ALEXANDER J. ELLIS

With a New Introduction (1954) by

HENRY MARGENAU

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC., NEW YORK

Copyright 1954 by Dover Publications, Inc. All rights reserved

This Dover edition, first published in 1954, is an unabridged and unaltered republication of the second (1885) edition of the Ellis translation of Die Lehre von den Tonempfindungen, as originally published by Longmans & Co. A new Introduction has been specially written for this Dover edition by Henry Margenau.

International Standard Book Number: 0-486-60753-4

Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation

60753422

www.doverpublications.com

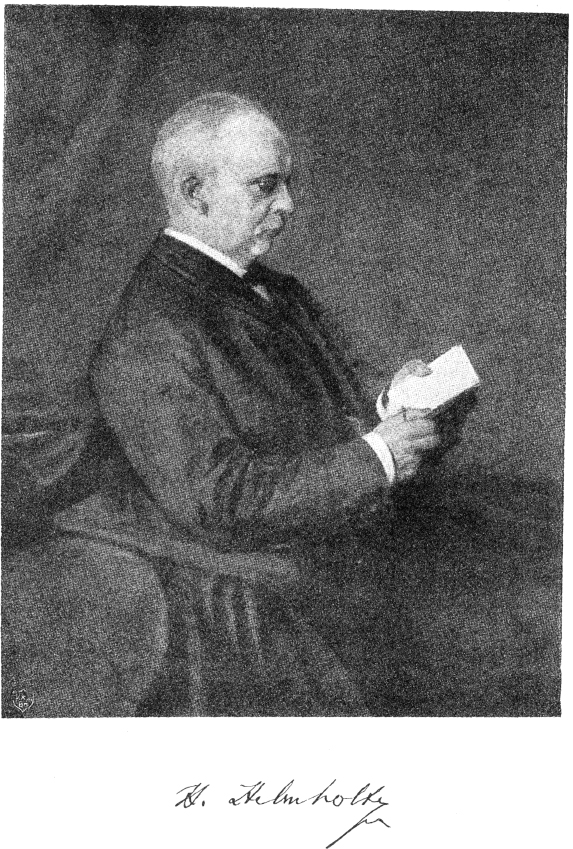

INTRODUCTION

BY HENRY MARGENAU

This book, reprinted more than 90 years after its first publication, is a magnum opus of one of the last great universalists of science. Figures like Helmholtz belong to a dying age in which a full synthetic view of nature was still possible, in which one man could not only unify the practice and teaching of medicine, physiology, anatomy and physics, but also relate these sciences significantly and lastingly to the fine arts. Added to this distinction of the book is yet another, a remarkable circumstance that is unique beyond the historical greatness of the work: its continued usefulness. The Sensations of Tone is still required reading for everyone who wishes to prepare himself for work in physiological acoustics, and the musician finds in it unexhausted treasure if he wishes to understand his art.

English readers are particularly fortunate in having available a translation that is excellent almost beyond belief. The clarity of Ellis prose and his careful choice of technical terms are in no small measure the occasion for the current value of Helmholtz contributions. This introduction, therefore, wishes to pay more than ordinary tribute to the distinguished translator and annotator whose technical competence in the field of acoustics and whose love of music enhanced the work in a major way. The reader owes Ellis a debt of gratitude for sparing him such literal translations as clang tint, proposed by Tyndall for the German Klangfarbe, and rendering it as quality. This term has now been generally adopted. The other interesting divergence in terminology which arose from Helmholtz use of the word Oberton has not been settled. Tyndall chose the misleading literal version of overtone while Ellis advocates upper partial. There can hardly be a question concerning the greater fitness of the latter phrase.

Since the book speaks for itself, this introduction can serve the reader best by acquainting him with the life of its author and with his astonishing accomplishments in other fields. To exemplify the account I shall append a chronological list of Helmholtz publications.

Hermann Ludwig Ferdinand Helmholtz was born on August 31, 1821 in Potsdam, the first child of Ferdinand Helmholtz, a teacher in the Gymnasium of that city. He was a sickly boy and, according to his mother, considered unattractive by all. However, she says, I was not worried about it; I admired my child, for whenever he opened his eyes he smiled at me and I saw nothing but spirit and intelligence. Illness interfered with the youngsters early training, but when, at the age of 9, he entered the Potsdam Gymnasium he proceeded rapidly, jumped grades and passed into his maturity at the age of 17. He himself, in reflecting upon this period 50 years later, recalls the difficulties he encountered in memorizing unrelated facts, grammar and vocabulary in particular annoyed him. History was his difficult subject; curiously, too, he says he had trouble in distinguishing left from right.

A pronounced interest in natural science developed early and led to the desire on the part of the boy to study physics. His father, however, had five children to support and saw no possibility of financing so expensive an academic course. He applied, therefore, to the medical institute (Friedrich-Wilhelms Institut) in Berlin for a scholarship which would enable Hermann to combine some work in physics with a regular course in medicine. The scholarship was awarded against the pledge that the candidate, after completing his studies, would spend several years as a military physician.

Thus Helmholtz became an lve at the Royal Medical and Surgical Friedrich-Wilhelms Institute in Berlin where he spent the years from 1838 to 1842. The freshman schedule at this school comprised forty-eight hours per week. Here he came under the influence of a great teacher, Johannes Mtller, whose advice and example largely determined Helmholtz career. The desire to combine physiology and physics manifestly stems from this early association with a great scientist. During that period, also, a lifelong friendship with Brcke and Du Bois-Reymond was formed. The work at the Institute led to a doctors degree, acquired at the age of 21 through a dissertation entitled De Fabrica Systematis Nervosi Evertebratorum, describing a fundamental anatomical discovery demonstrating that nerve fibers originate in ganglion cells. In 1843 the young military doctor entered service as surgeon in the regiment of the royal guards at Potsdam.

It was during this epoch that his thoughts turned increasingly toward the fundamental problem of the day, the principle of conservation of energy. The equivalence of heat and mechanical energy was known; perpetual motion was generally regarded as impossible. Following Liebig, Helmholtz investigated heat phenomena in muscle action. But his ambition rose beyond the wish to establish the conservation law merely in the realm of empirical fact; he set himself the task of deriving it from more fundamental principles and thus to exhibit it in its full generality.

This he accomplished in his famous lecture before the Physical Society of Berlin, on July 23, 1847. The substance of the lecture had been accumulated painstakingly during long hours of hospital duty; it represents one of the greatest scientific documents of all time. Beginning with two basic assumptions, (1) that all matter consists of mass particles and (2) that these interact by central forces, i.e. forces acting along the lines joining the particles, he was able to give a cogent proof of the conservation law. In his reasoning he introduced the idea of Spannkraft, the form of energy now generally called potential. The prestige acquired through publication of this paper permitted him to relinquish the duties of a military physician, and in 1848 Helmholtz took his first academic position; he became teacher of anatomy at the Academy for Fine Arts in Berlin. This minor post did not hold him long, for in 1849 he was called to Knigsberg as associate (ausserordentlicher) Professor of Physiology.

Having obtained a secure position, he married Olga von Velten, the daughter of a physician, and then turned to his important investigations concerning the speed of nerve impulses. According to the view then current these were so rapid as to escape detection, and astonishment was great when the young professor measured the speed along frog nerves and found it to be about 30m/sec. His discovery of the law of rise of an electric current in an inductive circuit, now named after him, fell into the beginning of the Knigsberg period. Indeed it is amusing to find him writing his father in the summer of 1850 that he has become the father of a healthy girl, but that so far as discoveries are concerned he has only a theorem regarding the rise of electrical currents to report. Moreover in the same year he invented the ophthalmoscope, that well-known device for illuminating the retina and studying its structure, which brought him fame in the medical world.

Next page