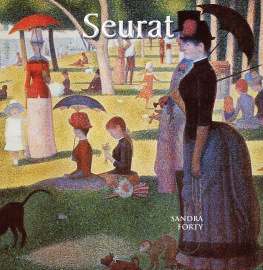

Georges Seurat

Georges Seurat

THE ART OF VISION

Michelle Foa

This publication is made possible in part by the Barr Ferree Foundation Fund for Publications, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University.

Copyright 2015 by Michelle Foa.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

yalebooks.com/art

Designed by Leslie Fitch Set in Crimson and Source Sans Pro type by Leslie Fitch Printed in China by Regent Publishing Services Limited

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014941271

ISBNs 978-0-300-20835-1 (cloth); 978-0-300-21282-2 (ebook)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper). 10987654321

Jacket illustrations: (front) Detail of , Georges Seurat, Parade de cirque, 188788.

Frontispiece: Detail of , Georges Seurat, Poseuses, 188688.

To Jeremy, Ethan,

and the memory of my father

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am happy to have the opportunity to thank in writing the people and institutions who have helped to make this book possible. Since this work originated as my doctoral dissertation at Princeton, I would like to begin by expressing my deep gratitude to Hal Foster, Rachel DeLue, and most of all Carol Armstrong for their support, insight, and guidance. Their feedback on the project continued to inform its development long after I left Princeton, and Im profoundly grateful to them for it, as well as for their advice over the years and for the models of intellectual rigor with which they provided me. In particular, Carols continued support for my work has meant a great deal to me, and she has my enduring thanks for all of her encouragement. I first studied art history as an undergraduate at Brown University, and it was my courses and conversations with Kermit Champa that made me want to become an art historian. I am grateful to him for that inspiration and for supporting my interest in continuing my studies in graduate school.

I was fortunate to spend a year teaching in the Department of Art History at Mount Holyoke College as I was finishing my dissertation, and I thank the faculty there for their warmth and collegiality. During that time I first met Bob Herbert, and I am indebted to him for the scholarly and personal generosity that he has shown to me ever since, and for all of his work on Seurat. Tulane has been a wonderful academic home since then, and I thank my colleagues in the Art Department for their intellectual stimulation and friendship. Thanks are also due to the Deans Office of the School of Liberal Arts, the Newcomb College Institute, and the Office of the Provost for the grants and fellowships they have awarded me to pursue my research and publish this book. I am grateful, as well, for the support that I received from The Barr Ferree Publication Fund of the Art and Archaeology Department at Princeton. Jim Rubin gave me tremendously valuable feedback on the manuscript at various stages, and he has my profound thanks for all of his wisdom and guidance. Gary Hatfields generous comments on my work, and my conversations with him, have been extremely helpful to me, and I am deeply appreciative of his input.

Talks that I have given over the years helped me to develop some of the arguments put forward here, and I am indebted to the organizers of those events, as well as to some of the fellow participants and audience members, for giving me the opportunity to present on my work and for their thought-provoking questions and comments, including: Kathryn Brown, Anthea Callen, Robin Kelsey, Marni Kessler, Sgolne Le Men, Sarah Linford, Yukio Lippit, David Lubin, Peter Pesic, Todd Porterfield, Chris Poggi, Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, Debora Silverman, Tania Woloshyn, and Henri Zerner.

Thanks also go to the staff at the following institutions for facilitating my research and granting me access to archival materials: The Philadelphia Museum of Art (and Joseph Rishel in particular), The Barnes Foundation, the Muse dOrsay, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Muse des Arts Dcoratifs, the Bibliothque de lInstitut national dhistoire de lart, the Bibliothque nationale de France, and the Bibliothque Forney. I am also grateful to all of the institutions and private collectors that provided me with reproductions for this book, and to my research assistant Aschely Cone for her hard work in helping me to acquire those images. I would also like to express my heartfelt gratitude to Katherine Boller at Yale University Press for her support for this project and for guiding it, and me, so smoothly and conscientiously through the publication process. Thanks are also owed to Heidi Downey and Amy Canonico at the Press for their work on this book, and to Deborah Bruce-Hostler for her copyediting of the manuscript.

On a personal note, I thank my mother, stepfather, and sisters for their support, and especially Jeremy and Ethan, who are so very important to my happiness. Finally, I thank my father, who showed me the joys of being immersed in books, pursuing ones curiosities, and sharing ones discoveries with others.

Introduction

Georges Seurat painted The Hospice and Lighthouse of Honfleur in the summer of 1886, one of seven paintings in a series that he produced of Honfleurs port and surrounding coastline (see ). The lighthouse in the middle ground is matched by one in the far background, visible, but just barely so, from where Seurat was standing. To the right of the lighthouse in the background is a jetty that stretches out into the water. These same lighthouses and jetties appear repeatedly in Seurats paintings of Honfleur, as the artist wandered from place to place around the port and produced a series of pictures portraying overlapping parts of the site. Between 1886 and 1890 (the last summer of his life) Seurat spent part of every summer but one in a different port town along Frances northern coast, each stay resulting in a series that consisted of somewhere between two and seven pictures. A few of the particularities vary from port to port and from series to series, but the underlying logic of these pictorial groupings is the same; each picture in a given series depicts a part of the larger site that is represented in or referred to by at least one other painting in that series. These are groups of images that track Seurats movements in space as he shifts from one vantage point to another to study the objects and spaces around him from a multiplicity of viewpoints, with each view, and each painting, supplementing the others. Seurats seascapes, then, center on extended visual and bodily engagement with ones surroundings, and thus fit in well with his long-standing reputation as an artist interested in visual experience and its pictorial representation.

It is this interest in vision that my book takes as its central focus. Indeed, few artists of the modern period are as closely associated with the subject of visual perception as Seurat. Within a few weeks of exhibiting A Sunday on the Grande Jatte1884 in the spring of 1886, Seurats work was associated by certain critics, most prominently Flix Fnon, with theories of how vision worked. Seurats reputation as an artist keenly interested in vision stayed with him throughout his short career and it lived on, in some form or other, in many subsequent accounts of his work. And yet there is much that we still dont understand about the subject. Indeed, it is surprising how little we know about what particular aspects of sight, besides color vision, interested Seurat, or about how, precisely, this interest in vision is reflected in his work, besides in his pointillist method of paint application. What did vision mean to Seurat, what model(s) of vision and its representation in pictures was he working with, and how, specifically, do his pictures manifest these concerns?

Next page