THE COMMERCE OF VISION

THE COMMERCE OF VISION

EARLY AMERICAN STUDIES

SERIES EDITORS:

Daniel K. Richter, Kathleen M. Brown, Max Cavitch, and David Waldstreicher

Exploring neglected aspects of our colonial, revolutionary, and early national history and culture, Early American Studies reinterprets familiar themes and events in fresh ways. Interdisciplinary in character, and with a special emphasis on the period from about 1600 to 1850, the series is published in partnership with the McNeil Center for Early American Studies.

A complete list of books in the series is available from the publisher.

THE COMMERCE OF

VISION

Optical Culture and Perception in Antebellum America

PETER JOHN BROWNLEE

Copyright 2019 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Brownlee, Peter John, author.

Title: The commerce of vision: optical culture and perception in antebellum America / Peter John Brownlee.

Other titles: Early American studies.

Description: 1st edition. | Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, [2018] | Series: Early American studies | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018020816 | ISBN 9780812250428 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Visual communicationUnited StatesHistory19th century. | Visual perceptionEconomic aspectsUnited StatesHistory19th century. | United StatesCommerceHistory19th century. | United StatesEconomic conditionsTo 1865. | Vision.

Classification: LCC P93.5 .B739 2018 | DDC 302.2/22dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018020816

CONTENTS

Color plates follow

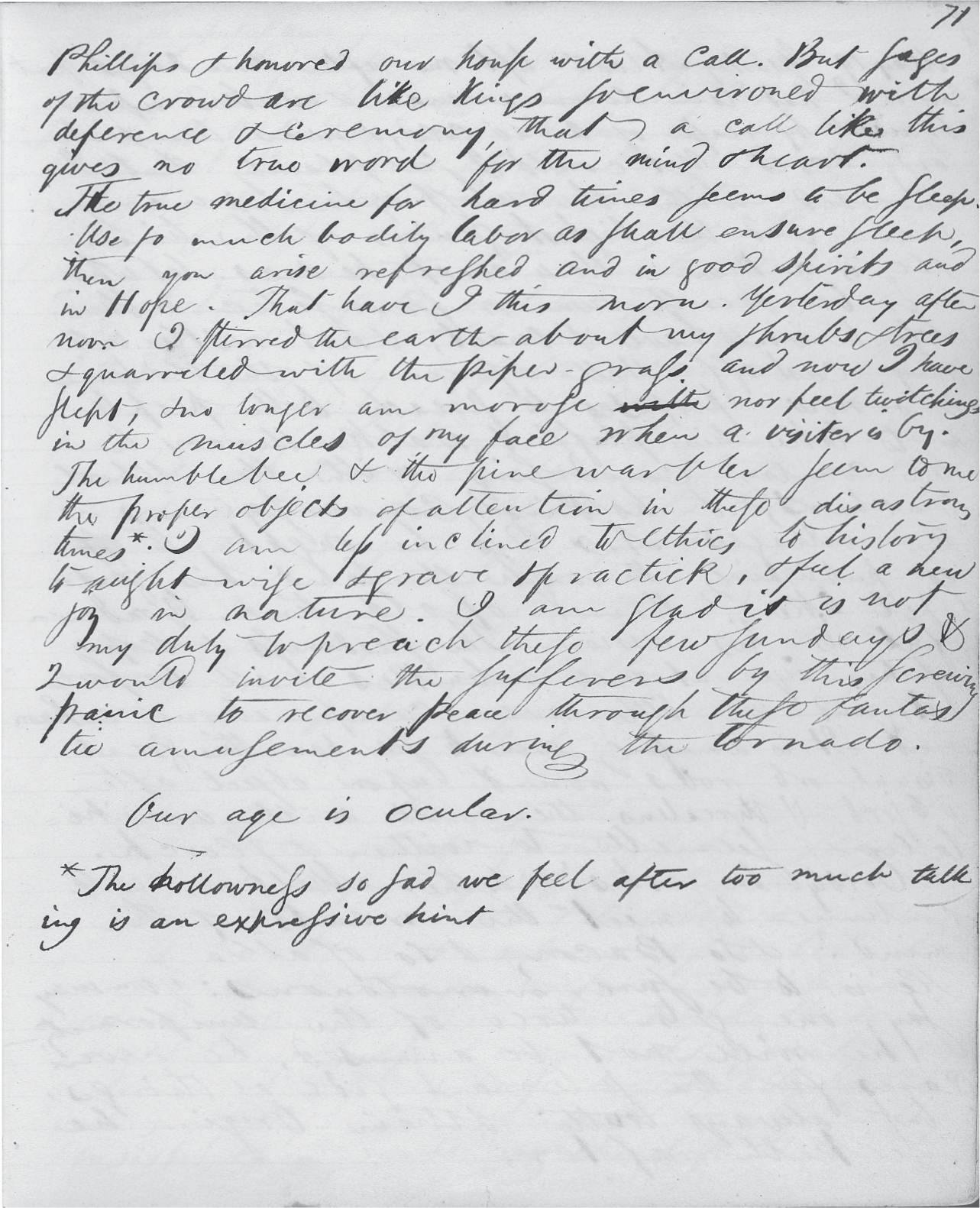

FIGURE 1. Ralph Waldo Emerson journals and notebooks, 1837, p. 71. Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

In a journal entry dated May 14, 1837, Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote: Harder times. Two days since, the suspension of specie payments by the New York and Boston banks.). The inscription is as vague and inscrutable as it is provocative. That he pairs it with the Panic of 1837 and the paper money economics of the period is one of the key subjects of this book.

Well before the collapse of the Second Bank of the United States, paper had become a central medium of exchange in antebellum America, circulating in the form of banknotes, handbills, broadsides, and newspapers. The age was ocular, to borrow Emersons elliptic phrase, because so much of its proliferating culture targeted the eyes: newspapers, pamphlets, books, posters, signs, popular prints, painting exhibitions, and spectacular entertainments. As something to be viewed, scanned, skimmed, or read, paper also functioned increasingly as a medium of perception, as a vehicle for a new kind of seeing. And just as these objects were intended to circulate, they were produced for people on the move, and thus remind us of the motility and mobility of observers and how these affected their perception. Amid this thriving print and visual culture, the eyes both saw and were seen. Eyes were considered the primary organ for visual experience and the accumulation of knowledge; yet, they were also, like so many other surfaces, to be scanned as one might gloss over a page of print. They were thought capable of penetrating discernment or indicative of a persons inner character, virtual windows onto the soul, and yet, they themselves often failed in fits of fatigue and overstimulation.

The Commerce of Vision attends to how vision was understood and experienced during this tumultuous period. To do so, it investigates how vision was rendered in the crowded visual field of antebellum America. The new visual experiences of the antebellum city produced new knowledge about visions capabilities and consequentially cultivated new perceptual practices, habits, and aptitudes. But these new experiences also highlighted visions shortcomings within a visual field increasingly defined by a print culture premised on mobility, ephemerality, and unbridled commerce. Shifting the focus of ones sight from the tiny print of newspapers, pamphlets, and periodicals to the boldest display types deployed on broadsides, posters, and signboards underscored for observers the necessity of maintaining the widest possible range of visual acuity. These forms stressed the importance of vision and emphasized its normal functioning as well as its thresholds and its limits. This thriving visual culture physically stressed the eyesight of observing subjects, while several of its many objects bore traces of the cultures reckoning with visions physiological processes and problems. Emerson, who suffered from a failure of his own vision in the mid-1820s yet posited sight as a key trope in his transcendental philosophy, knew this first hand.

Early in the essay Nature (1836), Emerson expounds on what has since become one of the most enduring symbols of his day: In the woods, we return to reason and faith. There I feel that nothing can befall me in life,no disgrace, no calamity (leaving me my eyes), which nature cannot repair. Standing on the bare ground,my head bathed by the blithe air and uplifted into infinite space,all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eyeball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or parcel of God.signifying his stake in the market economy, Cranchs figure vividly acknowledges that vision, as constituent of an age that is ocular, was ultimately grounded in broader intellectual, scientific, and commercial currents. As he wanders, the clouds above his head allude to the difficulty of seeing clearly amid the markets obfuscating surfaces and dense networks of exchange.

Similar to most Americans whose eyes failed them, Emersons own troubled eyesight provided the most instructive lessons in physiological optics. It is well known that Emerson suffered in the 1820s and early 30s from a partial loss of sight resulting from a bout with tuberculosis. Reynoldss treatment was successful, allowing Emerson to continue writing and lecturing. His plight reveals that as the market system increasingly targeted the sensory capacities of human bodies in order to attract or interpellate and position them as consumers, Americans came to locate the properties, processes, and problems of vision in their own bodies, as well as in their fiscal ability to correct and maintain it.

With the emergence of physiological optics in the 1830s and 40s, and interrelated developments in the growing field of applied ophthalmogy, the mechanics of vision could no longer be explained without reference to the physiological functions of the human body. Thus the dematerialized model of vision demonstrated by the monocular camera obscura was largely abandoned, first in scientific circles and later by the public at large. Experimental physiology and applied ophthalmology revealed instead that the eyes aqueous humors functioned in tandem with the retina in producing and maintaining sensation. Studies of binocular vision, which would eventually assume the popular form of the stereoscope, revealed that the eyes functioned as a pair, rather than separately, to enable a wider field of view and greater depth perception, as well as an array of other eye movements critical to properly functioning vision. So while the monocular, all-seeing eye continued to circulate widely in the visual field, its symbolic currency and cultural relevance faded as the model of vision it promulgated lost its utility in the imagination of a public whose eyes were diseased, malformed, or otherwise disfunctional. Abandoning the theoretical conceit that eyes, whether symbolic or actual, could enable an objective or godlike view, Americans became active stewards of their own vision and came to understand vision as

Next page

THE COMMERCE OF VISION

THE COMMERCE OF VISION