Contents

Guide

THE

PREDATOR

AND VARMINT

HUNTERS

GUIDEBOOK

BY PATRICK MEITIN

CONTENTS

DEDICATION

For my father, who rekindled my passion for varmint shooting, tack-driving firearms and precision reloading on a grand scale after a long absence. And, of course, my loving wife, who puts up with all my scattered gear and long absences.

Chapter 1

Why Predators &

Varmints?

Born and raised in the West and close to open spaces, I began hunting early, tagging my first rifle mule deer when 10 or 11 and my first elk at 14 (with my own handloads). Because of this early initiation, the transition into muzzleloaders and then serious bowhunting was a predictable progression. By the time I graduated high school, Id forsaken big-game hunting with rifles, becoming a dyed-in-the-wool bowhunter in my late teens and not shooting a big-game animal with rifle for more than 25 years. Yet I maintained a full arsenal of rifles and handguns and continued avidly handloading, forever seeking more accurate loads for every firearm I owned. This had everything to do with varmints and, to a larger extent, predator hunting, as I never have seen a coyote I didnt desperately want to shoot. Despite bowhunting as the cornerstone to my big-game journey, I never lost my fascination with firearms and their use in pursuing small varmints and predators.

Varmint is a term tossed about loosely, with many inclined to include any small-game species. The official definition is an American-English colloquialism of vermin, representing animals that are considered a nuisance to man, and/or unprotected by game laws. Further, varmints are animals widely believed to spread disease or inclined to destroy crops, livestock or other private property. Strictly speaking, varmints do not include common small-game species such as cottontail rabbits, snowshoe hares or tree squirrels, though those species often exhibit pest-like behavior just ask the backyard gardener or bird-feeder enthusiast. These popular small-game animals are rightly official game in most states in addition to providing excellent table fare. There is also the designation of predator including foxes, bobcats and coyotes and these are often afforded seasons, but also frequently considered vermin.

So, licensing and/or season restrictions are no sure demarcation between varmint and genuine small-game or furbearer status, as many states require permits to shoot even nongame species. Idaho, for example, requires a hunting license to shoot ground squirrels (definite vermin) and coyotes (known livestock killers), and Oregon requires hunting licenses for varmints on public but not private lands. Colorado requires a hunting license for varmints such as marmots or prairie dogs (and rattlesnakes) and has instituted highly defined seasons the sure mark of a blue state. Texas, despite exploding populations of invasive feral hogs and resulting depredation, requires nonresidents to purchase a nongame license even while hunting private lands that Texas Parks and Wildlife invests zero resources to maintain. This, of course, says as much of the bureaucrats lust for revenue as it does management concerns.

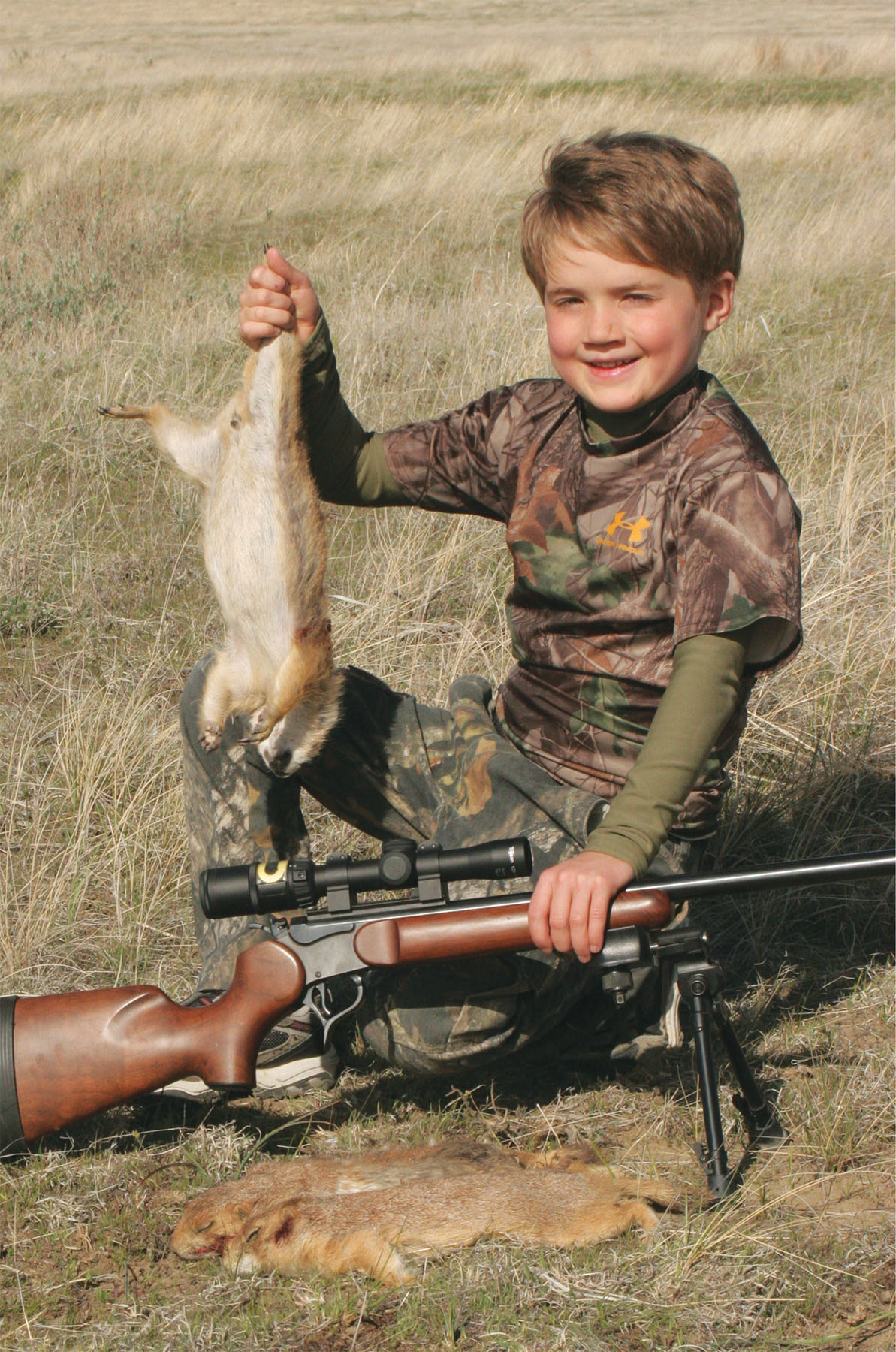

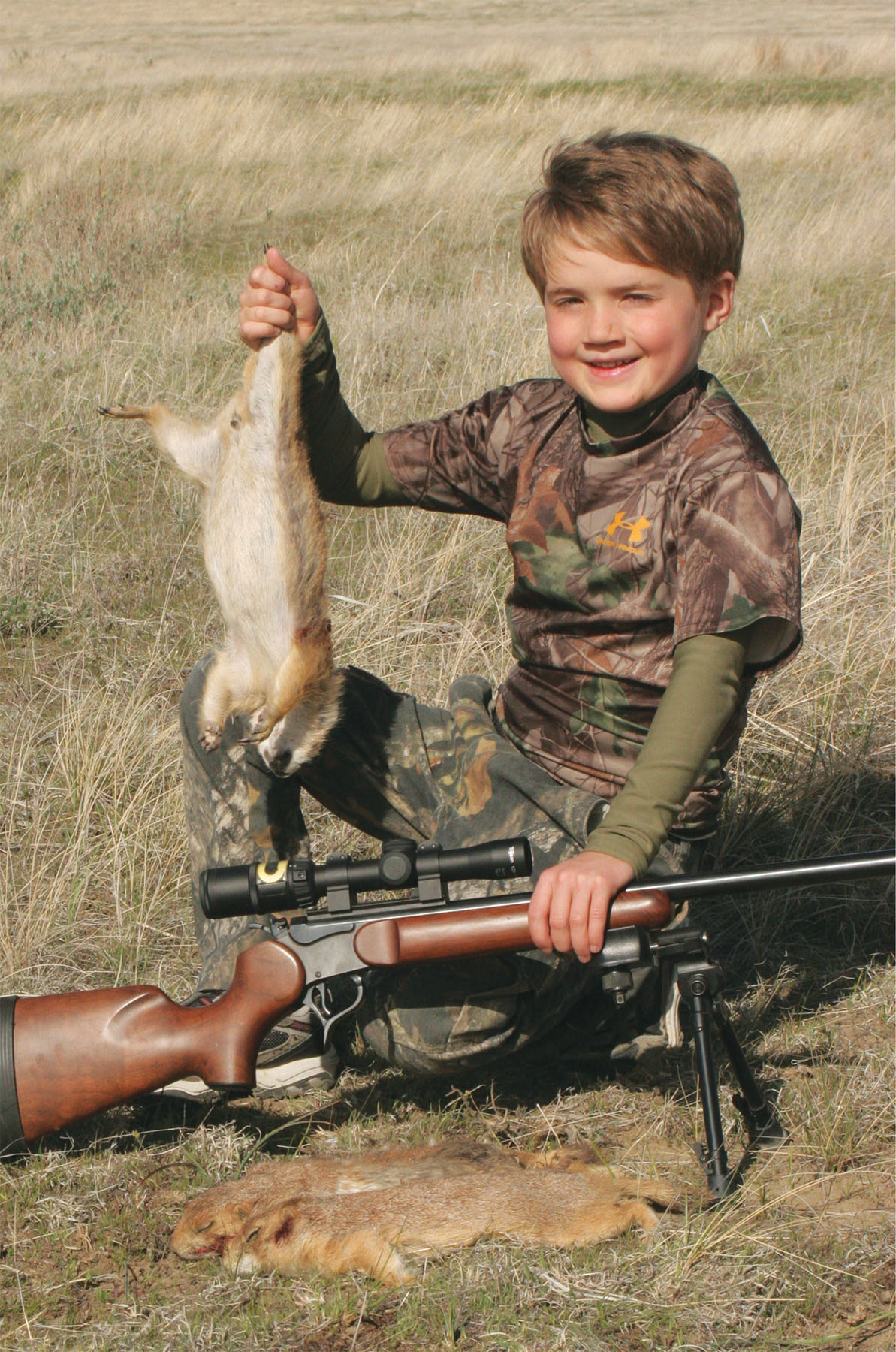

There is no better way to get a youngster hooked on shooting than through small varmint shooting. The nonstop action keeps short attention spans from wandering and beats videos games any day. Scott Haugen photo.

The author enjoys varmint shooting as much for the time he spends with his father as the shooting itself. This kind of quality time is difficult to find in these hectic times, even while big-game hunting.

And lets get something straight from the beginning: Im the farthest thing from a conquer-the-wilderness, Manifest Destiny type who believes every corner of North America must be made comfortable for livestock at the expense of all other living creatures. There is a balance to everything, even varmints and predators, and besides, if an animal is going to be eliminated from the landscape, it isnt going to be by my bullets but rather a landowners poison. And for our purposes, just to keep things tidy, varmint will specify smaller rodents and birds meeting the aforementioned definitions, and predator will mean common furbearing fauna such as foxes, bobcats and coyotes.

So the legitimate question becomes, why all the fuss about varmints and predators? The easy answer is that varmint shooting and predator hunting (calling usually) is just plain fun. The more involved answer is that varmints, predators and nongame species offer a fun, relaxing, rewarding and extremely affordable way for average blue-collar sportsmen (and ladies) to more thoroughly enjoy the shooting sports. And lets be frank: Although we might work under the mantle of pest elimination, we shoot not with the veniality of day traders but the zeal of children devouring ice cream.

Another harsh reality: Big-game hunting has become increasingly expensive with each decade. Quality big-game property has grown progressively more difficult to access, mostly because of the bane of the modern hunting lease and well-heeled hunters willingness to pay top dollar to keep prime habitats to themselves. Even in areas with abundant public lands, top-quality big-game licenses in proven trophy areas are secured only through low-odds lottery drawings after accumulating the correct number of preference points or by purchasing expensive landowner tags. Its easy for the average working man to feel left out.

Varmint and predator hunting allow easier access to private lands (by helping thin destructive pests), year-round seasons for many species and fewer regulations and permit requirements in short, the ability for a serious firearms enthusiast to stay engaged and sated. Interestingly, even varmints go only to the highest bidder in select locations, and guided varmint shoots and lodges are now more common than ever. But in the bigger picture, varmints are still largely wide open to those willing to do their homework.

More private ground is locked up each year because of hunting leases or landowners fearful of a litigious society. Helping eliminate vermin can help a shooter get his foot in the door and gain access to prime private properties.

For many, varmint shooting and predator hunting offer welcome off-season sport. Here in northern Idaho, for example, after the last general big-game season passes in early December, theres nothing to look forward to but a long, tedious winter of ice-fishing (no thanks), snowmobiling (cant afford it) or skiing (over it). Predator calling becomes my way of avoiding the creeping shack nasties, getting me out of the house and busy with something challenging and rewarding that sometimes actually pays for itself via the raw-fur trade. In New Mexico, when winter doldrums got me down, there was productive predator calling in the offing, but for an uncomplicated, carefree afternoon stroll, it was difficult to beat jackrabbit hunting.

In fact, superfluous jackrabbits (and prairie dogs) are what I honed my rifle-shooting skills on while young and building big-game ambitions. I was lucky to work on large ranches during summer vacations, bucking hay for 10 cents a bale, or traversing large ranchlands pitching hay to starving cows and checking watering tanks during drought months, years before I earned an official drivers license. A rifle of some sort invariably rode along. Throughout my formative years, I treated my .243 Win. Remington 700 ADL like a .22 Long Rifle, handloading 100 rounds of Sierra 60-grain hollow-points at a time and shooting every one of them at jacks, prairie dogs or occasional thirteen-lined ground squirrels while making ranch rounds. Another landowner, an alfalfa farmer I worked for sporadically, supplied a friend and me bricks of .22 LR shells, a farm pickup and 10-cent-each bounty for jacks, encouraging nighttime spotlighting on his sprawling alfalfa fields. We regularly filled pickup beds with dead hares.