Thank you for purchasing this Deer and Deer Hunting eBook.

Sign up for our newsletter and receive special offers, access to free content, and information on the latest new releases and must-have deer and deer hunting resources! Plus, receive a coupon code to use on your first purchase from ShopDeerHunting.com for signing up.

or visit us online to sign up at

http://deeranddeerhunting.com/ebook-promo

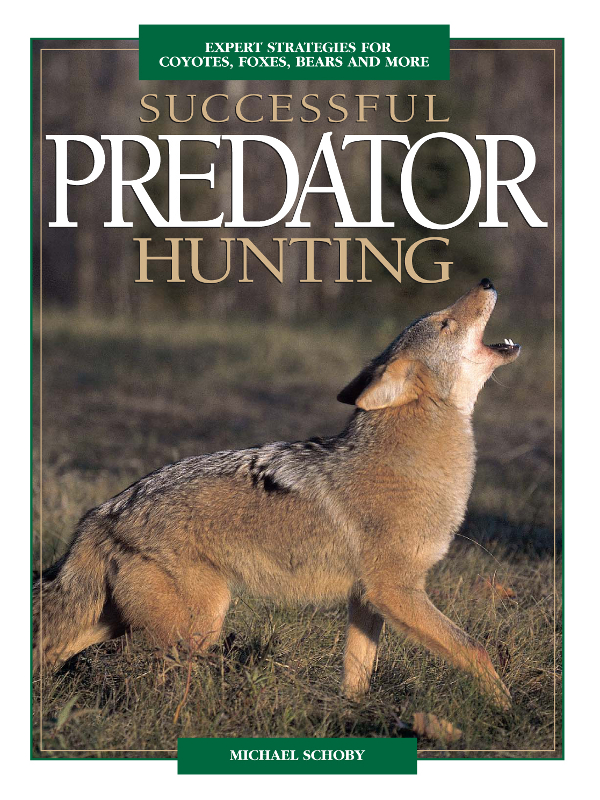

Copyright 2003 by Michael Schoby

All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a critical article or review to be printed in a magazine or newspaper, or electronically transmitted on radio or television.

Published by

700 East State Iola, WI 54990-0001

715-445-2214 888-457-2873

Please call for our free catalog. Our toll-free number to place an order or obtain a free catalog is 800-258-0929 or please use our regular business telephone 715-445-2214.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2003105286

ISBN: 0-87349-544-6

Printed in the United States of America

eISBN: 978-1-44022-480-5

Dedication

To my father, who started me along the outdoor trail.

Table of Contents

Photo by Mitch Kezar

Foreword

I believe that all of us who are hunters dream of hunting strange and magnificent creatures in the far-flung corners of the globe: animals such as grizzly, Cape buffalo, wild sheep, greater kudu; places with exotic names like Yukon, Serengeti, Pamir, and Kalahari. Some of us are fortunate enough to realize some of these dreams, but it really doesnt matter. We are all hunters. Despite our dreams and desires, and whether or not we are able to make some of them come true, most of us spend the majority of our precious time afield hunting game that is most available in our own backyards.

It has always been so. In the 1920s, my Kansas-born grandfather hunted the vast numbers of waterfowl that traded down the Kansas and Missouri rivers. The dust bowl of the 1930s followed years of uncontrolled market hunting, and the stream of ducks dwindled to a slow trickle. My grandfather became an upland bird hunter. My father was raised hunting quail and pheasants over good bird dogs. So was I, 20 years later. But things changed again. Farming got cleaner and bigger, and many of the brushy hedgerows and streambeds disappeared and as the human population increased and good upland bird habitat grew more scarce, no hunting signs became ever more prevalent.

During this same period, many of the new impoundments and reservoirs matured, and conservation efforts brought back the waterfowl geese in unprecedented numbers, and more ducks than any member of my generation had ever seen. My quail and pheasant hunting buddies got duck boats, decoys and retrievers and became waterfowl hunters. The whitetail population exploded as well, and these same hunters whose fathers had never owned centerfire rifles became deer hunters, and today can argue the virtues of .270s and .300 magnums just as well as they could discuss the advantages of over/unders versus semiautos and pumps a couple of decades earlier.

So what does all this have to do with varmint hunting and, more specifically, predator hunting? Hunters are hunters, and nationwide, most of them will always hunt the game thats most available closest to home. Across the country right now, opportunity to hunt varmints is not only at an all-time high, but for many of us represents the class of game that is most plentiful, most available, and most affordable. There are many reasons for this. Pluses for the varmints include cessation of poisoning as a means of control; and, for furbearers, cessation of trapping and an all-time low in fur prices. These have led to booms in predator populations. Coyotes are now found from coast to coast, and fox and bobcat populations are also burgeoning. Black bears, classed as big game with resultant protection, are rapidly increasing in both population and range. Cougars are as well.

For the hunter, this translates into opportunity, with some extra pluses as well. Unlike big game, upland game and waterfowl, in most areas seasons for predators and other varmints are long (often year-round), and hunting licenses (if required at all) are basic and inexpensive. Bag limits are generally nonexistent. Of course, in this day and age one of the real keys to hunting is a place to hunt. This is also much simpler for varmints than for any other class of game. Farmers and ranchers who wouldnt consider allowing access for deer or upland game are often downright grateful to have predator callers and prairie dog and chuck shooters on their lands. In fact, with poisoning and trapping a thing of the past, varmint hunters are now the single most important tools for maintaining predator and rodent populations in an acceptable balance.

As you will see in this book, there is an extensive range of equipment that might be used in predator hunting: sophisticated calls, specialized rifles, decoys, portable blinds, night vision devices, and more. If used (and always, if used correctly), such equipment offers an advantage and probably adds to both success and enjoyment. But the actual requirements for successful varmint hunting are actually very simple: an inexpensive mouth- blown call, a reasonably appropriate firearm, basic camouflage and a bit of knowledge. Compare this to the dogs, decoys, boats, blinds and duck leases serious water-fowlers find essential today.

In the 1920s and 1930s, when big-game populations were at their nadir, varmint hunting was an extremely popular sport in many parts of the country. In my younger days, it was considered primarily an off-season pastime. For many it still is, but for the reasons mentioned above availability, access, affordability today there is an unprecedented interest in varminting, with growing numbers of sportsmen and women considering it their primary hunting focus, interrupted only by short seasons for other game.

Michael Schoby is just enough younger than I am (lucky guy!) that this is the world he came into as a hunter. Growing up in Washingtons Cascades, he had the benefit of excellent (but short) seasons for deer and elk. But as a teenager he recognized that his best hunting opportunity (available, accessible, affordable) was offered by the plentiful predators in his neighborhood not only coyotes and bobcats, but black bears and cougars as well. He was 14 when he called in his first coyote, and in the many years since has remained fascinated by the tactics, techniques and downright excitement involved with hunting predators. As he told me, There were several years in my early 20s when I hunted predators year round and nothing else.