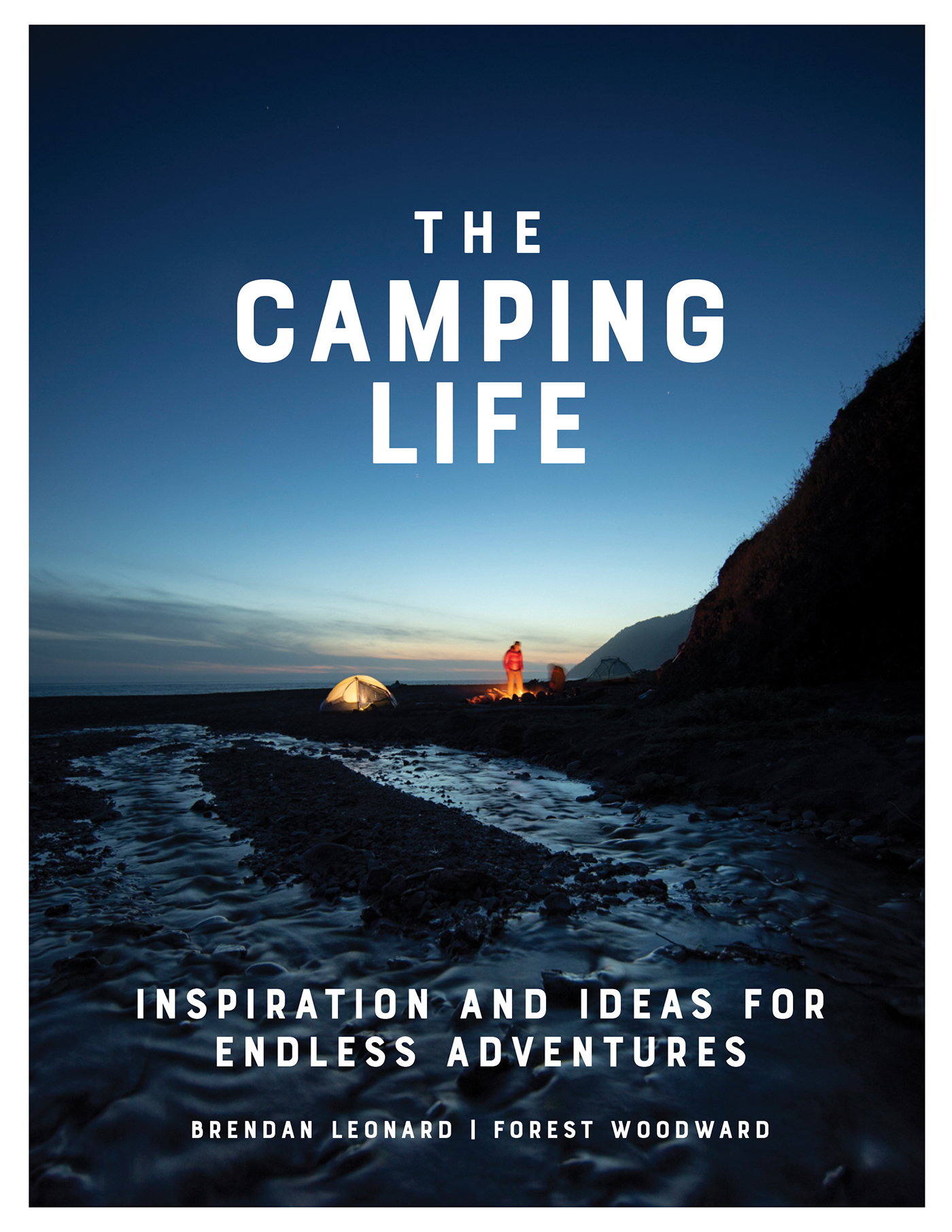

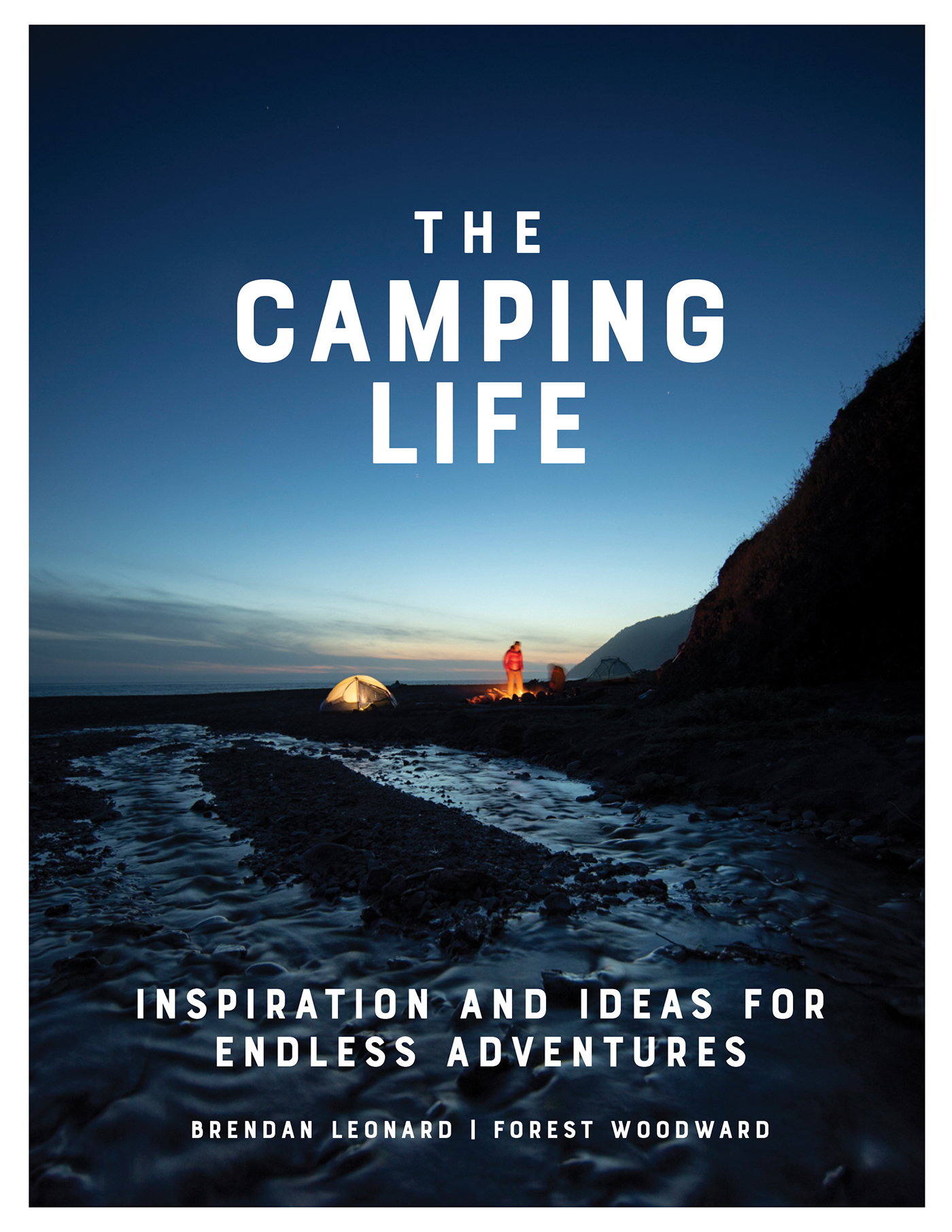

THE CAMPING LIFE

inspiration and ideas for endless adventures

Brendan Leonard | Forest Woodward

artisan | New York

Sometimes all you need is to climb a simple hill, to spend time staring at an empty horizon, to jump into a cold river or sleep under the stars, or perhaps share a whisky at a small country inn in order to remind yourself what matters most to you in life.

Alastair Humphreys, Microadventures: Local Discoveries for Great Escapes

Contents

Introduction

by Brendan Leonard

While scrolling through my phone one day, I came across an interesting quote about nature: how a huge number of us were discovering we needed it as an antidote to our hyperconnected, always-on, drinking-from-the-data-firehose lives. It was a pertinent quote for 2020, when you might find yourself in a coffee shop, looking up from your laptop to take a five-second break from fifteen open browser tabs and ever-multiplying e-mails and see everyone else looking at some sort of glowing screen or two, trying to keep up with their own personalized stream of information.

Except the quote I read was not from 2020it was from 1901, when John Muir wrote it in Our National Parks:

Thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, over-civilized people are beginning to find out that going to the mountains is going home; that wildness is a necessity.

If John Muir noticed in 1901 that people needed wildness to deal with civilizationback before e-mail, before texting, before cell phonesimagine what he would think now. And how much more we probably need wildness in our lives these days, with our overflowing inboxes, pocket computers that buzz with notifications all day, and twenty-four-hour news cycles.

Theres a real thing that happens to all of us when we run away from all that electronic chatter and into the wildness John Muir was talking about: As we drive away from cities and towns and toward the mountains or forests, we notice that our cell service is gradually becoming spotty. We become anxious at first: What if someone at work needs to get a hold of me? (Yes, even on Saturday.) What if I miss something on Instagram or Twitter? What if some sort of national news happens and I dont read an article about it right away, or for a day or two? We rapid-fire through apps, trying to get one last update before we lose contact.

As we drive farther, our cell phone service fades more and more. Eventually, we arrive at a campground or at a trailhead where we begin walking or biking to a campsite somewhere. At some point, we either lose cell service altogether or we become frustrated trying to refresh our e-mail inbox with one lone bar of service, and we give up. Our phones are now useless. We have no choice: We are present. In nature.

Somehow, without a constant stream of data, we manage to fill the time: setting up tents, unrolling sleeping bags, sitting on rocks, maybe reading paperbacks, walking to waterfalls or mountain views, building campfires and sitting and staring at them as if they were streaming consecutive episodes of our favorite Netflix shows. And were fine.

The more days were away from the information-industrial complex and in the woods, the less we care. Sure, maybe we miss our spouse, friends, parents, or kids, but not so much our office, and definitely not social media or the newsthe only news we need is whether its going to rain today. After a couple of days, we may wonder if we actually need to go back to our house, our to-do lists, our job at all. Certainly if anything has come up at work after two or three days, everyone at the office has figured out the solution by now, right? Cant we just live here, with no e-mail and with campfires every night?

Of course, we cant, and we all eventually go back to civilization. But on returning, we have memories, some stories, and photos we might put on our end-of-year holiday cards. By getting away from all the stuff we think we need on a daily (or hourly) basis, weve created something memorable, a narrative that rises above all the information wrangling and logistics of our everyday lives. We have something to talk about when someone asks, What have you been up to?

John Muir famously would take off into the Sierra Nevada range with hardly any supplies or equipment besides a bit of bread and tea, and he once spent the night near the snow-covered summit of Mount Shasta in California, next to a volcanic steam vent for warmth. Thankfully, we have much improved equipment and food nowadays, and roughing it can be a lot less rough.

This book is designed to inspire you to step away from the noise and get out there, whether out there is one-night camping at a state or county park thirty minutes from your house, a weeklong hut-to-hut trip in the Alps, or a sixteen-day raft trip through the Grand Canyon. Were all busy, and any time away is a gift, even if its a weekend or two a year.

To immerse yourself in the outdoor experience, you dont have to sleep on a portalege suspended a thousand feet up a rock-climbing route or in a tent on a snowfield at ten thousand feet on the side of a volcano (although well cover these styles of camping). The point of a night in a campground with flush toilets and a night out in the desert twenty miles from the nearest road is the same: Connecting with nature. Feeling the wind on your face, listening to raindrops on a tent fly, breathing air filtered by a stand of pine trees. And not caring if you have mud on your shoes or if your clothes smell like campfire smoke.

One of the most famous Muir quotesyouve surely seen it on a T-shirt, sticker, or Instagram biois The mountains are calling and I must go. For sure, were in a moment on this planet where we all have a million things pulling at usbut we can still hear that call from the mountains. Or the desert or the forest or the river. And its arguably one of the most importantor at least one of the most memorablecalls we can answer.

Packing List: All-Purpose Camping Gear

Next page