Jake Tyler

A WALK FROM THE WILD EDGE

PENGUIN BOOKS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

New Zealand | India | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published by Michael Joseph in 2021

Copyright Jake Tyler, 2021

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Jacket artwork by Dave Buonaguidi

Cover images Shutterstock

This book is a work of non-fiction based on the experiences and recollections of the author. In some cases the names of people or details of places or events have been changed to protect the privacy of others.

ISBN: 978-0-241-40118-7

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

For Mum

The terrain on the upper section of Ben Nevis looked like the surface of the moon no plants, no grass, no fungi, no life at all; just a vast plain of small grey rocks edging towards the sky. As I perched a thousand metres above the Nevis Forest, breathing plumes of thick mist, I noticed a little white bird that had landed ten yards or so away from me, on a rock in the gap between two precipices. It was a snow bunting. Some people, Id heard, climbed the mountain just to catch a glimpse of it. It glanced nonchalantly at me, sharing the moment, before it took off and plunged into the dense white cloud between the rocks. In those few seconds of silent appreciation, I realized that I was completely at ease. At ease in my surroundings. At ease in myself. I belonged there, almost as much as the bunting. And as I continued my ascent, the sound of the rocks crunching beneath my boots, my thoughts drifted back to that morning when Id forgotten that it was possible to feel so alive.

1

March 2016

In just the past month Id thought of nine or ten ways I could do it. Sticking my head in the oven felt like it would leave the least amount of mess; using a knife would take some serious bottle, more than I felt I had; and while throwing myself in front of a train at Stratford would probably get the job done, the psychological impact on the driver and everyone on the platform was just too awful to think about, and not something I wanted to be responsible for.

Id been living like a wounded animal for weeks, too hurt to move, begging to be put out of its misery. I longed to eat something I didnt know I was allergic to, to be stabbed in the street, to have an undiagnosed heart condition. But of all the versions of death I could dream up, the one I fantasized about the most was jumping from the room on the fourth storey, above the bar. I imagined standing on the ledge, staring down at a world I didnt understand, a world full of people I didnt feel any sort of kinship with. I imagined a sudden gust of wind, cold and hostile, slapping me across the face, before I took one last breath of dank, polluted London air and released myself, from the ledge and from my rotten, disintegrated life, feeling the briefest rush of terror and adrenaline course through me as I plunged head first towards the pavement.

and then, just like that, itd all be over. Dreamless sleep forever and ever. No pain, no hate, no sadness. Abrupt, blissful nothingness.

But despite obsessing about death, allowing the image of falling through the air to get clearer and more visceral over time, the thought of killing myself was a desire, not an option. I honestly never thought Id go through with it at least, not until that morning.

My shift had ended early. Bethnal Green Road had been quiet, even for a weeknight, resulting in probably the most peaceful evening Id seen at the Well and Bucket since Id agreed to take over as manager eight months previously. It was typically a very busy haunt located off the top of Brick Lane on the fashionable Shoreditch/Bethnal Green border, it was renowned for good food and good, interesting booze, and was tastefully decorated with dark wooden floors, a polished brass bar, and crumbling tiles from Britains Regency era clinging desperately to the walls. It served as a landmark of sorts, a solid piece of Londons social history, and it remained a popular choice with the hordes of young professionals and artisan-spirit purveyors of east London.

After over a decade spent slinging pints and mopping up vomit in Brightons thriving but slightly mucky bar scene, I had been excited to be asked to oversee a venue with that much class and history. However, only a couple of months in, my initial enthusiasm had begun to fade, and my excitement about landing the dream job was replaced by an intense, rotting feeling inside me that I didnt understand. Something was happening to me. Something was wrong. And what terrified me the most was that I didnt know how to fix it.

That night, after ushering out the last few stragglers, I cashed up and joined my staff for a post-shift drink, slightly earlier than usual. We congregated in our usual spot on the side of the bar nearest the tiled wall beneath three large Victorian portraits with human skulls superimposed over the faces. I sat there for hours, silently knocking back can after can of half-chilled Camden Hells, half-listening to the usual gossip about customers, friends and current flings, staring at the paintings. They had a macabre quality, and looking at them made me feel closer to death, in a way that was more comfortable than it should have been. I looked towards the ceiling, picturing my room on the fourth floor, and realized that I felt no sense of comfort in doing so.

My bosses hated the idea of me living above the pub, and for good reason. With no clear divide between my job and any sanctuary, I was constantly on high alert and spent most of my time off lying in bed, flinching at every sound that came from the floors below like a dog in a storm. My room was a truthful reflection of how I viewed myself cold, bare and void of any charm or personality. Waking up in that room every day made me feel like the lowest of the low; lacking even the most basic self-respect to keep it habitable. My hygiene routine had run aground a few weeks previously, and slumping into bed without showering at the end of the night was now a regular thing. Looking into a mirror for longer than a second was starting to torment me, and running my tongue across my teeth felt like licking the felt on an old pub pool table. I was in poor shape, in every conceivable way. And I had never felt so alone.

I thought I had to avoid being found out at all costs and, whenever I felt this way, whenever my mind told me how shit I was, I buried it. I buried it in shallow holes, never deep enough to cover it up completely, so when the working day was over and I was by myself, the feelings re-emerged.

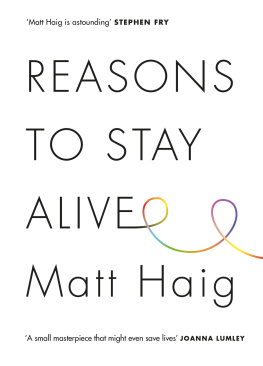

Id always felt that there were two versions of Jake. Version one is confident, engaged, talkative, has the guts to take on just about anything; version two is quiet, unable to think straight and unsure of who he is. In my mind, V2 posed a constant threat to my more desirable self, V1. V2 was, in my eyes, the most pathetic individual that has ever lived. Its unsettling writing about myself like this Id never dream of being so brutal to another human being the way I sometimes am to myself.