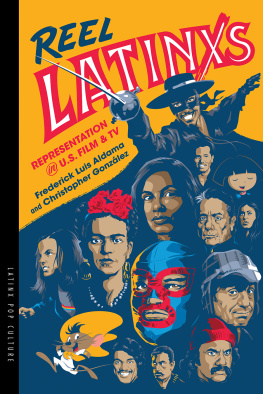

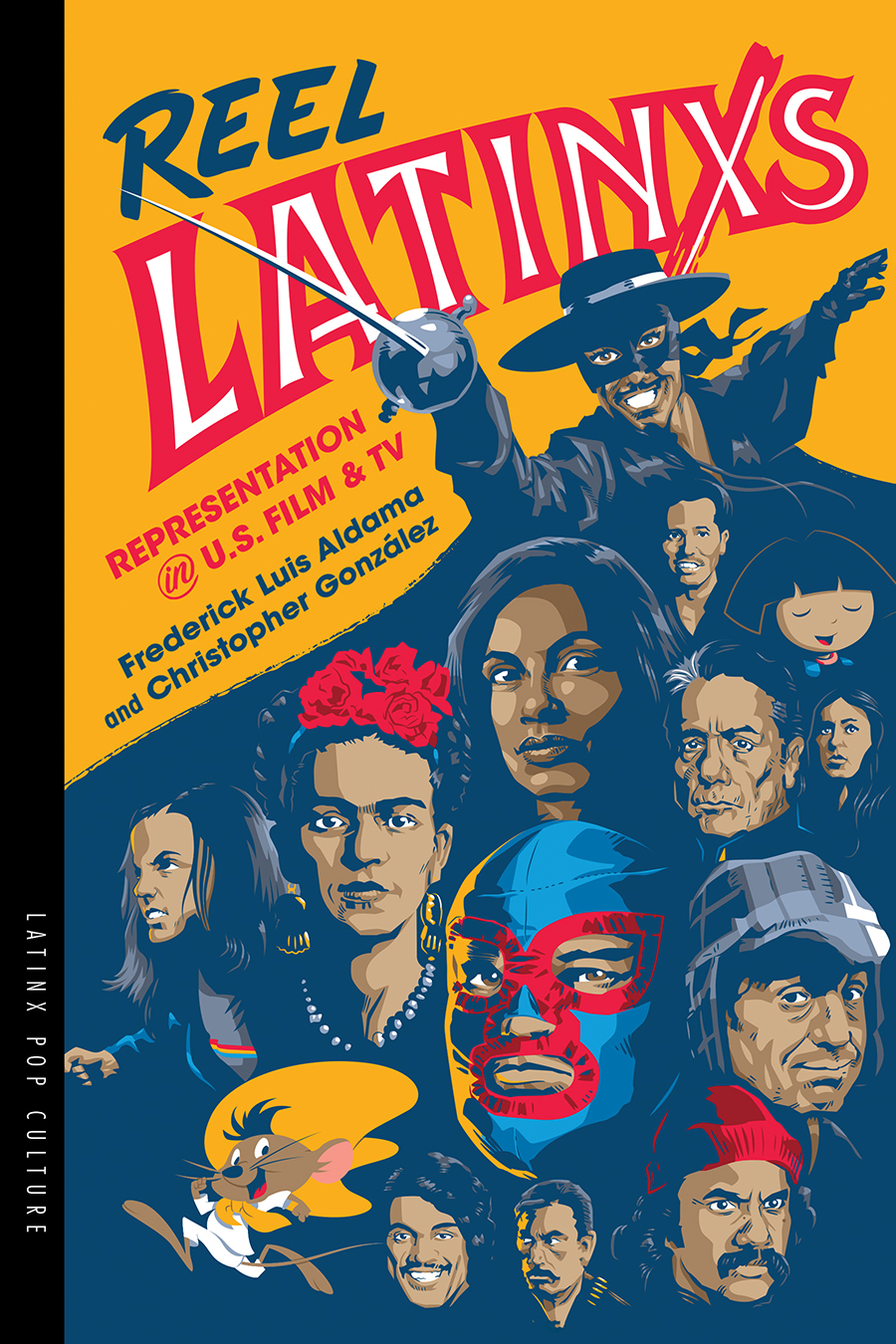

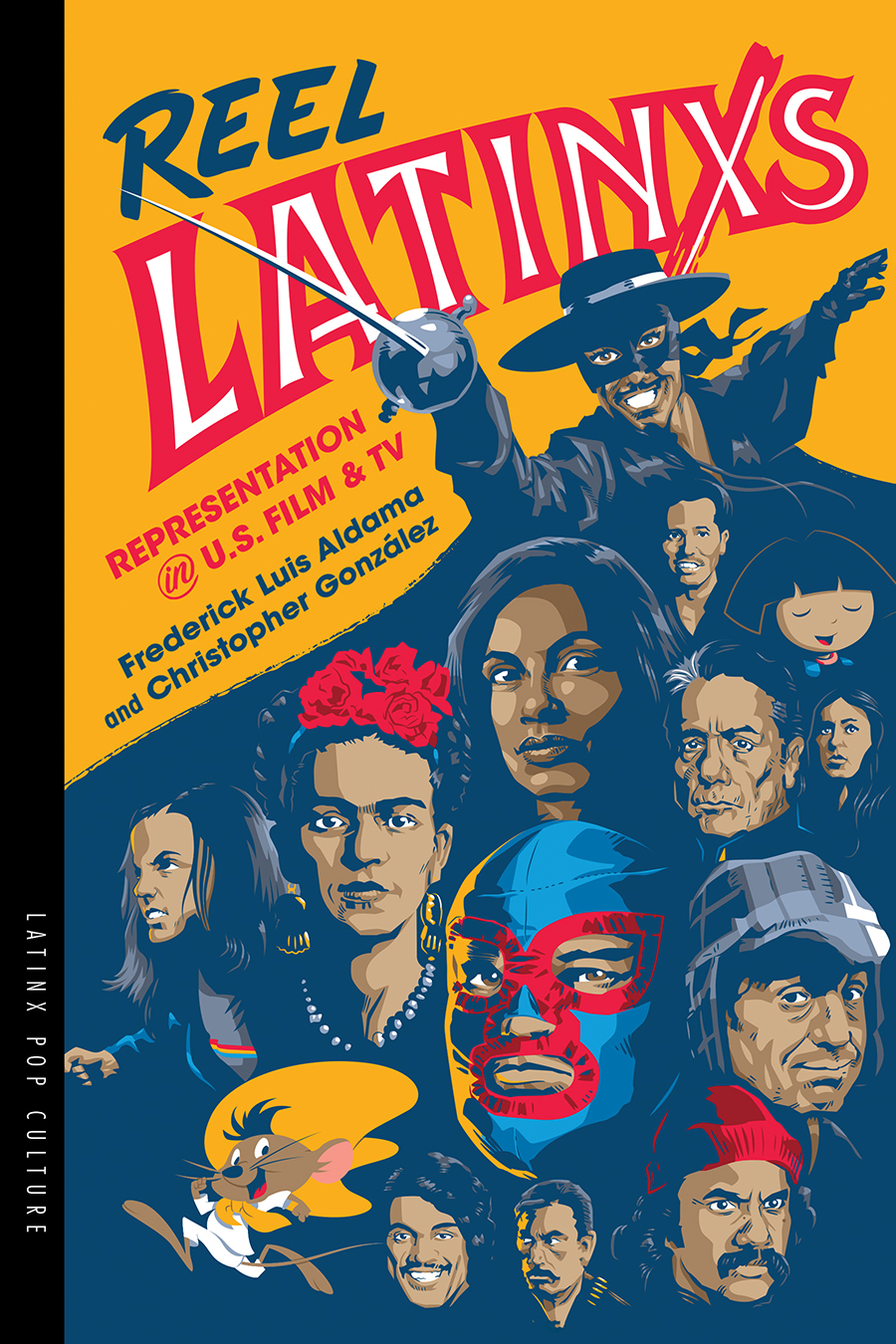

Reel Latinxs

Latinx Pop Culture

Series Editors

Frederick Luis Aldama and Arturo J. Aldama

Reel Latinxs

Representation in U.S. Film and TV

Frederick Luis Aldama and Christopher Gonzlez

The University of Arizona Press

www.uapress.arizona.edu

2019 by The Arizona Board of Regents

All rights reserved. Published 2019

ISBN-13: 978-0-8165-3958-1 (paper)

Cover design by Leigh McDonald

Cover art by J. Gonzo

Publication of this book is made possible in part by funding from subventions from the College of Humanities and Social Sciences, Utah State University, and from the Department of English, Utah State University.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Aldama, Frederick Luis, 1969 author. | Gonzlez, Christopher, author.

Title: Reel Latinxs : representation in U.S. film and TV / Frederick Luis Aldama and Christopher Gonzlez.

Other titles: Latinx pop culture.

Description: Tucson : The University of Arizona Press, 2019. | Series: Latinx pop culture | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: This book explores the representations of Latinx in mainstream film and television. The authors provide a roadmap through the history of Latinx misrepresentation, including character types, sexuality, and casting issues, and discuss the disproportionate appearance of Latinx in films and TV despite their growing demographic in the United StatesProvided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019005816 | ISBN 9780816539581 (paperback)

Subjects: LCSH: Hispanic Americans in motion pictures. | Hispanic Americans on television.

Classification: LCC PN1995.9.H47 A43 2019 | DDC 791.43/652968073dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019005816

Printed in the United States of America

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

For our nias

Contents

Preface

Latinx Pop Culture Matters

After each of us had spent years lecturing and writing on Latinx pop culture, we decided to sit down together and write a book on the subject. Cocos smashing box-office records lit the fire. That Disney/Pixar finally reached beyond Speedy Gonzales comfort zones and actually hired Latinxs (after initial backlash when they did not consult Latinxs) to voice the characters; consult on the story, culture, and history; and assist with the films helming was a watershed. And that the movie cleared upward of $740 million at the box office in the United States and abroadspurred on by all the Latinx families in the United States and those in Mexico and South America who poured into theatersshowed the world that, indeed, the distillation and reconstruction of Latinx culture, experience, and subjectivity mattered. It was a win-winfor the corporate moneymakers and for us. Unfortunately, Coco is exceptional in this regard. And we think its important to share with you the long history of why.

As this book will begin to lay out, the representation of Latinxs in mainstream television and film is not only plagued by willful misrepresentations but also is completely out of step with Latinx demographic presence in the United States. As our numbers have grownand today we, the Latinxs of the United States, are steadfastly the majority minority with 50 million plusthis misrepresentation has become even more obvious and shameful. With Latinxs already the majority population in the Southwest and growing most abundantly in the South and Midwest, no matter where one lives today, one is bound to see, engage with, and even know a Latinx person. As Chris Rock said of the nearly all-white Oscars in 2016, you really have to go out of your way not to find a Latinx in L.A. So, in spite of what some have identified as the Browning of America, producers and creators in Hollywood and mainstream TV continue to either look the other way, deliberately erase us, or lazily turn their attention to stereotypes of yesteryear: from the malapropistic Speedy (whoever thought arriba arriba means go go?) to those banditos in Westerns and comic books to hypersexualized spitfire Latinas.

Friz Freleng and Hawley Pratts Speedy Gonzales created for Warner Brothers Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies cartoon series

At the same time that we think a roadmap through the history of our misrepresentation is necessary, we also see within this history moments of rupture. Sometimes in the most unexpected places in mainstream TV and film, Latinx subjectivities have been reconstructed in complex ways. We think not only of some recent prime-time shows such as Cristela (20142015), Superstore (2015), and the even more nuanced all-Latinx casted reboot of One Day at a Time (20172019), but also of shows such as CHiPs (19771983) and Chico and the Man (19741978). And so, while the general trajectory of Latinx representation has been one that nearly flatlines a simplistic and racist reconstruction of Latinx subjectivity and experience, there have been moments when we see a definite heartbeat, as we will examine throughout this book.

Before going any further, a quick word about our use of the term Latinx. For many decades, peoples in the United States who trace their roots to Latin America and have Spanish-speaking ancestors have struggled with an adequate and acceptable term of identity. Latin, Hispanic, Spanish, Mexican American, Chicano, Latina/o, Latin@, and many more identity terms have found their way into discussions of the exploration and expression of heritage. And all have, in some way, been found wanting. There is, therefore, no definitive term that satisfies everyone, as Suzanne Oboler has extensively observed. The most recent term for this community is Latinx (pronounced Latin-ex or LaTEEN-ex), with the x signifying a gender-neutral identity label that refrains from making an assumption about a person. The term began appearing on social media in 2014, and its usage has steadily grown (Salinas Jr. and Lozano, 1). We use the term throughout the book as a reminder of inclusivity and openness even though we recognize that not everyone is completely comfortable with the term and that many in the general public may not even understand yet what the term connotes. Conversely, not all scholars who work with any of the myriad of issues concerning this community accept the term Latinx unproblematically, if at all. Indeed, several scholars, including Richard T. Rodrguez, have written compellingly about the troubled nature of the term. Nevertheless, we believe the use of the term here, despite any shortcomings it may have, does the important work of signaling inclusivity. For us, the x also marks the wound of a shared colonized legacy of exploitation and oppression. We would like to state that we are aware of the ever-evolving nature of labels (per Oboler), and we take up the term with the knowledge that the x, as Rodrguez (203) notes, may cross out or omit something important to someone who may read this. We also considered varying the terms we use (i.e., Latinx sometimes,

Next page