Latinx Pop Culture

SERIES EDITORS

Frederick Luis Aldama and Arturo J. Aldama

The University of Arizona Press

www.uapress.arizona.edu

2017 by The Arizona Board of Regents

All rights reserved. Published 2017

Printed in the United States of America

22 21 20 19 18 17 6 5 4 3 2 1

ISBN-13: 978-0-8165-3708-2 (paper)

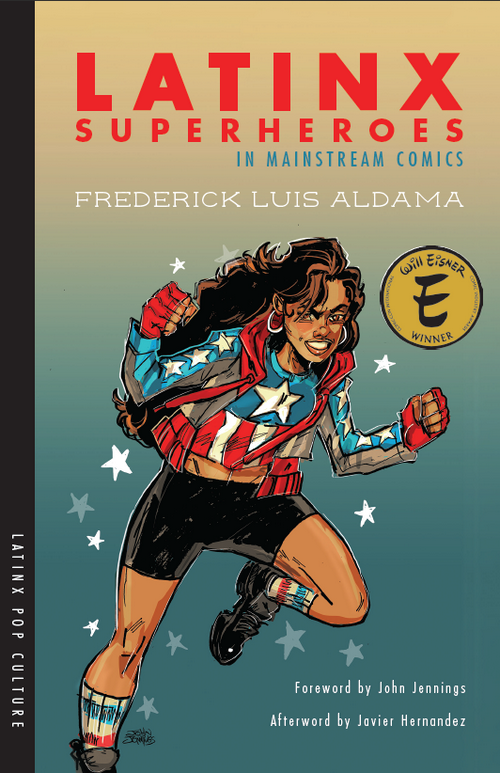

Cover design by Leigh McDonald

Cover art: America Chavez by John Jennings

Publication of this book is made possible in part by the proceeds of a permanent endowment created with the assistance of a Challenge Grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, a federal agency.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Aldama, Frederick Luis, 1969 author. | Jennings, John, 1970 writer of foreword. | Hernandez, Javier, 1966 writer of afterword.

Title: Latinx superheroes in mainstream comics / Frederick Luis Aldama ; foreword by John Jennings ; afterword by Javier Hernandez.

Description: Tucson : The University of Arizona Press, 2017. | Series: Latinx pop culture | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017010449 | ISBN 9780816537082 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Comic books, strips, etc.United StatesHistory and criticism. | Hispanic Americans in literature. | Hispanic Americans in popular culture. | Superheroes. | Comic books, strips, etc.Social aspectsUnited States. | Popular cultureUnited States.

Classification: LCC PN6725 .A37 2017 | DDC 741.5/352968073dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017010449

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

ISBN-13: 978-0-8165-3738-9 (electronic)

For Corina Isabel,

my very own Latinx comic book aficionado in the making

You have the right not to utter racial, ethnic or genetic slurs.

ANGELA DEL TORO, WHITE TIGER

Samuel Alejandro!... Donde te habias metido?... Acabas de salir del hospital... Mom, English por favor.

SAM ALEJANDRO AS THE NEW NOVA, MARVEL NOW! NOVA

Ay dios! America Chavez! Stop this running around at once. You must come home... We saved the world and left you a utopia... And you run away from it!

THE TWO MAMAS OF LGBT TEEN AMERICA CHAVEZ, YOUNG AVENGERS

ITS HARD BEING INVISIBLE

A Foreword

Growing up black, poor, and Southern made sure of my imperceptibility to the mainstream. So, like most invisible people, I turned to stories in popular media to start to build some sense of self to reflect back to my burgeoning psyche. Despite integration, the school I attended was pretty much 100 percent African American. However, I didnt really think about race in the media I consumed. My favorite comic book superheroes were all white, cisgender, straight men from large cities. They were basically the opposite of me. I didnt realize this at the time, but thats the truth of being born into the United States socially constructed identity matrices we are presented with even before we are born in the USA.

My mother introduced me to reading at an early age. She was an English literature major, and she had plenty of her college books around. She invested heavily, as much as she could, in my learning habits, and I fell in love with knowledge. However, when she bought me my first comics, The Mighty Thor and Spider-Man, little did she know that she was starting an obsession that would fuel my artwork, my career, and my life.

My favorite superhero is Daredevil. A tough Irish bookworm from Hells Kitchen, New York City; a place I had never been to and had no real conception of was my index for identity. I related to his poverty. I related to him being taunted by bullies. I related to him feeling isolated and odd. The thing I loved most about the character wasnt the superpowers that he gained later. I loved his grithis tenacity to keep going. I learned about how to struggle through that character, and not through a black character. Luke Cage, The Falcon, and Black Panther were cool enough, but they were never written in a manner with which I could connect. I could understand what it meant to go hungry, to feel small, and to want to succeed. I was Matt Murdock. I honestly didnt understand the weight of what it meant to be codified as black until January 23, 1977. That was the first airing of the original ABC miniseries Roots, based on the Alex Haley novel. My complexion is much lighter than thatof my grandfathers, but his skin looked like the skin of these people who were being hurt, shamed, enslaved, and controlled. I then realized through subsequent viewings that my lighter skin was due to two or more races mixing. The notion that a country that I pledged allegiance to every day in school would be based on something as horrible as chattel slavery broke my seven-year-old mind. That realization hurt me deeply. Those representations changed my life. My eyes saw my school, my teachers, and the absence of white students in our classes very differently after that miniseries ended. Comics became even more of an escape after I realized not only my social status, but also my inferior status as a black person in the South.

During graduate school at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, I began to realize my political attitudes toward representation, comics, and identity. I was coming closer to the perspectives that I now hold dear. It wasnt until my time teaching at that same institution a few years later that I recognized my calling. I began collaborating on independent comics and creating comic book communities inclusive of intersectional identities: race, ethnicity, sexuality, gender, and class. It was also the first time that I met Frederick Aldama. Little did I know that I was meeting not just a kindred spirit but also an inspirational figure, in my own pursuit of equity.

My favorite character, Daredevil, had augmented senses that gave his perceptions no blind spots. All of his senses were heightened to superhuman levels, and he possessed a kind of radar that enabled him to do things that normal humans couldnt. His handicap was his own character and even his Catholic faith. He is a very complex and compelling protagonist in that regard. You see, we all have blind spots. There are always spaces that are basically the shape of an absence in our worldviews. They behave like that space that Stephen King described in his novel, The Dead Zone. Its a space that is incomplete. It is also a space for potential change.

As a black scholar, it almost seems clich for me to study black identity, black history, and black cultural production. My own me-search has taken me far and wide talking about comics, stereotypes, social justice, and the power of symbolic annihilation. That focus can also become a blindness. You can become so intensely knowledgeable about the depth, width, and shape of yourown navel that you cant see anything else. You can see this happening with a patriarchal lens, a lens based in class, or even one that comes from a particular area of study or faith. That expertise can be a weakness. That notion is one of the reasons why I love interdisciplinary research and critically creative exercises. Its one of the reasons why I love what Frederick does with his passion. He strives to bring everyone together through his fiction, his social justice work, and his scholarship. I learn something every time I hear him speak. My blind spots get smaller after every conversation.

This book goes in depth regarding part of a tradition of storytelling that has excluded just as much as it has empowered. It shines a light on creators and characters that were just in the peripheral vision of popular culture. You have to understand that to not show something is just as powerful as showing something.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).