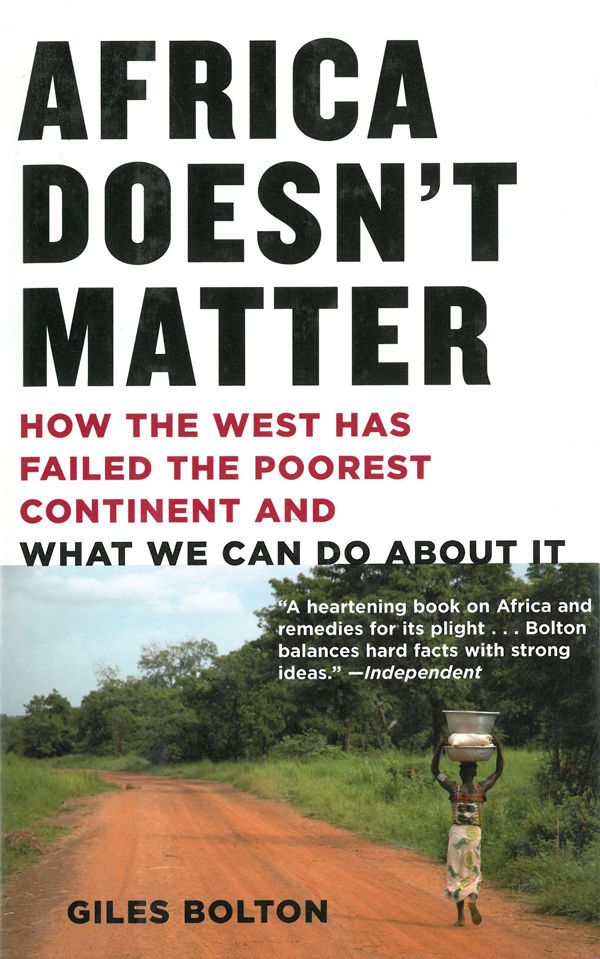

Copyright 2007, 2008, 2012 by Giles Bolton

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Arcade Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Arcade Publishing is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

First published in the United Kingdom in 2007 by Ebury Press as Poor Story.

Visit our website at www.arcadepub.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-61145-306-5

Printed in the United States of America

For my parents

CONTENTS

Introduction

3 President for a Day

8 Aid Betrayed

12 It Doesnt Work for You Either

14 Screw You, Too

18 Guilt or Glory

INTRODUCTION

It was the singer Michael Bolton who smoothed my first entrance into Africa.

In 1996 I'd gone to visit a friend in Kenya whom I'd met in college. The flight path into Nairobi is truly spectacular. If you ever happen to take the overnight Kenya Airways shuttle from London, try and get a window seat on the left as the plane faces forward. Dawn breaks at about the same time you pass west of Mount Kenya, and if you're lucky you get to see its three peaks printed onto a mustard sunrise. From there you follow the Rift Valley south until the arid beige land rises suddenly underneath and you flip over the ridge of the Ngong Hills and cruise down gently over the khaki contours of Nairobi National Park into Jomo Kenyatta International Airport.

Inside the terminal, things were neither as sweaty nor as chaotic as the stereotypes had taught me to expect. But the abrupt immigration official who eventually deigned to consider my passport wasn't doing much for international relations until he read my name. He looked up for the first time.

Ah, Bolton. Like Michael Bolton!

Um, yes, I suppose so.

Are you related to him?

No. Sorry.

Never mind. His music is very good. Enjoy your stay. The purple stamp thwacked down onto a clean page and I was in, vowing never to mock soft rockers again. My friend Alex had come to collect me, and as we drove out of the airport into a cool, bright morning, he flicked on the radio. In the thirty minutes it took to reach his house we were regaled with songs by Phil Collins, Bryan Adams, and Rick Astley. Michael Bolton notwithstanding, my first impressions of what the West had brought Africa weren't impressive at all.

Two weeks later, however, I was hooked. Back home I was about to start what I hoped would be a long career in the aid industrya journey that in a few years would have me running the largest aid program in Rwanda, one of Africa's poorest countriesand my vacation was enough to persuade me that, music scene aside, this was the place I wanted to be.

I'll be honest: some of the attraction for a palm treeaddled mind was the vacationer's glamorous lifestyle. We'd made ramshackle camps in the most mind-blowing of expansive rocky landscapes, spent long, hot days scrambling through leopard caves to emerge into blinding blue-skied panoramas, and savored star-swamped evenings around dancing flames. Privileged Africa is truly something to experience.

But I'd also long wanted to do Something Constructive, and equally fascinating to me had been a glimpse of everyday Kenyan life. Here was a country totally different from my ownwith different rules, dreams, expectations, and desires. And often astonishingly poor, from the rag-clothed community we'd seen cutting salt from a baking-hot crater in Kenya's barren north to the cramped slum's corrugated roofs that stretched rustily across a whole Nairobi valley, only to disappear from view entirely at night for lack of electricity. Surely these were problems the rich world could do something to address?

Three hours before my plane left, I stood looking over the scrub of the Athi plains, with a beautiful holiday romance in my arms and a dust-dyed sunset warming our faces. (Note: every book written by westerners about Africa has to feature a beautiful sunset, so it's good to get this out of the way early.) I was going to make a difference. I vowed to return as soon as possible.

The idea that westerners hold the key to Africa's development is, of course, a mythnot to mention patronizing. As I quickly learned, most of the answers lie, as they should, in the hands of African countries themselves and especially their governments. Corruption, conflict, and lack of democracy: all three are primarily internal problems, and the frequent failure of the continent's governments to achieve progress in these areas is depressing.

But if it's up to African countries to get their show on the road, it's the duty of America, Europe, and other rich regions to ensure there's a road to travel downbecause it's they who set the rules both for the aid Africa receives and the system of international trade it must abide by. How come none of the forty-eight nations south of the Sahara have made sustained progress since most achieved independence in the 1960s, bar one or two states with exceptional natural resources? They haven't all been run badly, all of the time; more than thirty are now democracies. It was the one region of the world to decline economically in the 1980s and 1990s, and though the last few years have seen a welcome return to economic growth, thanks largely to a surge in prices for the few basic commodities the continent supplies, the overall numbers in absolute poverty have increased. The fear is that our era of globalization simply isn't working for Africa.

This book is written for people who are concerned about Africa but don't understand why it's still so poor. While there is quite a bit of good academic material out there, most of it isn't very accessible and it doesn't answer the direct questions most of us want answered. Is Africa's poverty all down to corruption? What actually happens to our aid money, and how do trade rules affect us at the checkout line? Can the United States and other rich countries really make a difference in Africa? These are the practical concerns I want to tackle. And I want to explain why, for all the campaigns, concerts, and politicians' promises to make poverty history, Africa will remain poor and we in the West complicit in its plight unless we change the way we're allowing globalization to develop.

O n July 8, 2005, George W. Bush and the leaders of the world's seven other most industrialized nations, the G8, sat down to morning coffee in the bay-windowed Glendevon Room of the prestigious Gleneagles golf hotel in Scotland. What happened next was startlingly unusual: the leaders began a detailed discussion of Africa's problems and the West's part in their solutions. Never before had they devoted so much time to considering the predicament of the poorest continent. Never before had they acknowledged so openly that current arrangements, including the West's part in them, weren't working.

The G8's focus on Africa was no fluke, no sudden outbreak of altruism in a foreign policy world that nowadays feels so gloomily full of threats. The run-up to Gleneagles had seen hundreds of thousands of people across the West join protests demanding fairer aid and trade terms for Africa, despite the fact that the majority had never been there. Millions attended rock concerts from Philadelphia to London to Tokyo that sang from the same hymnal (though Stevie Wonder was, it's true, a big draw), while billions more watched on TV.