Contents

Guide

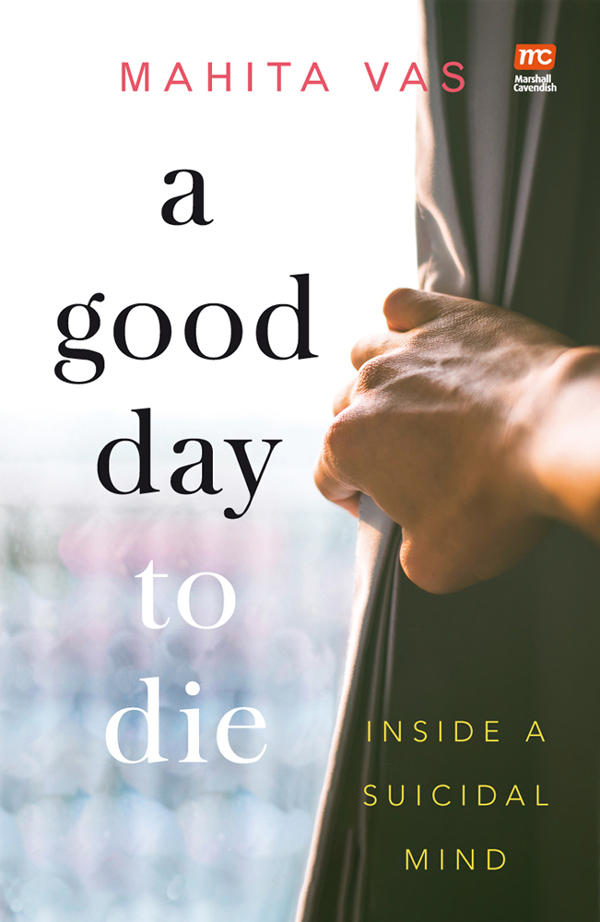

a good day to die

Inside a Suicidal Mind

by

Mahita Vas

Text Mahita Vas

2021 Marshall Cavendish International (Asia) Private Limited

Published in 2021 by Marshall Cavendish Editions

An imprint of Marshall Cavendish International

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Requests for permission should be addressed to the Publisher, Marshall Cavendish International (Asia) Private Limited, 1 New Industrial Road, Singapore 536196. Tel: (65) 6213 9300 E-mail:

The publisher makes no representation or warranties with respect to the contents of this book, and specifically disclaims any implied warranties or merchantability or fitness for any particular purpose, and shall in no event be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damage, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

Other Marshall Cavendish Offices:

Marshall Cavendish Corporation, 800 Westchester Ave, Suite N-641, Rye Brook, NY 10573, USA Marshall Cavendish International (Thailand) Co Ltd, 253 Asoke, 16th Floor, Sukhumvit 21 Road, Klongtoey Nua, Wattana, Bangkok 10110, Thailand Marshall Cavendish (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd, Times Subang, Lot 46, Subang Hi-Tech Industrial Park, Batu Tiga, 40000 Shah Alam, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia

Marshall Cavendish is a registered trademark of Times Publishing Limited

National Library Board, Singapore Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

Names: Vas, Mahita.

Title: A good day to die : inside a suicidal mind / by Mahita Vas.

Description: Singapore : Marshall Cavendish Editions, 2021. | Includes bibliographic references.

Identifiers: OCN 1244800111 | eISBN 978 981 4974 79 0

Subjects: LCSH: Vas, MahitaMental health. | Suicidal behaviorSingaporePsychological aspects. | Manic-depressive personsSingapore.

Classification: DDC 616.858445dc23

Printed in Singapore

For Debbie Fordyce & Ylita Garland

Foreword

A number of similar posts appeared on my news feed one morning in August 2020. The first line read, There were a total of 400 reported suicides in Singapore in 2019 , followed by another, Youth suicides still a concern, with 94 cases last year , and I finally stopped scrolling when this headline hit me, Suicide remains leading cause of death for those aged 10 to 29 in Singapore Horrified, I clicked to read the report. The figures were released as part of a highly publicised campaign by Samaritans of Singapore to introduce a text-based service for anyone in distress and contemplating suicide. The report, presented as a fact sheet and devoid of emotion, provided a clearer picture of the numbers: a total of 400 suicides, of which 94 were youths, which included 71 who were between the ages of 20 and 29. Noticeably, the report omitted the actual figures for the suicides of the younger group, but a quick calculation showed that, of the 94 youths who killed themselves, 23 were between the ages of 10 and 19. I froze, staring at the numbers, feeling numb.

The sobering effect of the report piqued my curiosity and I was keen to learn how Singapore compared with the rest of the world. According to the World Health Organisation, globally, nearly 800,000 people kill themselves every year one person every 40 seconds. Suicide is the leading cause of death in young people between the ages of 15 and 19. For every suicide there are many more people who attempt suicide every year. A prior suicide attempt is the single most important risk factor for suicide in the general population.

I had never bothered with suicide statistics, but reading of a ten-year-olds suicide in Singapore troubled me deeply. I searched for information his background, his circumstances but could not find any. In the process of looking, I learnt about another young boy who had committed suicide by jumping off the 16th floor of a building. He was only 11 years old and had been battling clinical depression. I read about how his mother coped with his sudden and unexpected death, and was in awe of a woman who, battling depression herself, had recognised the signs and sought help for her son years earlier.

I thought about the pain and anguish my late mother would have had to deal with had I been successful with my attempt 15 years ago. I thought about my husband and children, who might still be carrying the scars. I do not think anyone ever really comes to terms with a loved one wanting to, and choosing to, die.

For most people, certainly everyone I know, being alive is something they either take for granted, or treasure as a precious gift. For the faithful, it is a bountiful blessing. Being alive means soaking up experiences on any day. Like basking in the warmth of a sunny day after days of torrential rain, or admiring the varied hues and shapes of vegetables at the market, or savouring every mouthful of a meal, whether at a hawker centre, at home or in a restaurant, or hugging someone the little things that remind us all that life is precious, and something to value. Death is something to stave off, perhaps even to fear.

For me, being alive often feels the same as it does for most people. But, sometimes, I contemplate death not only as an option, but as salvation. Having survived a prior suicide attempt, I am considered a risk factor for suicide in the general population.

In Singapore, if you or someone you know is suicidal, please call 1800 221 4444 for help. If someone is in immediate danger, please call 999.

In other countries, please call your local emergency number.

Samaritans of Singapore (SOS) Media Release, August 2020

World Health Organisation Fact Sheet / Detail / Suicide September 2019

Chapter 1

I have had a morbid fascination with death since I was in my teens. Specifically, suicide. It was not as if I needed to run away from hardship. My mind simply gravitated towards stories about death; murder and suicide were topics of great interest to my young mind. It seemed natural to me, and I never thought to question my preference. It helped that there were always enough such stories in the newspapers to keep me entertained. With every suicide report I read, I wondered what it would feel like, standing at the top of a block of flats, and jumping to my death. It did not horrify me to think of such a violent death. The local broadsheet was particularly good for international news which was not limited to politics, and sometimes reported on gruesome murders in a village in some distant land. Captivating as some of the stories were, I would feel angry if the killers were not caught, and equally happy if they were, especially if they were killed.

By the time I was in my early twenties, I had become aware of my suicidal thoughts and was increasingly keen on suicide as a subject. My job as a stewardess took me to cities which were often shut on weekends, leaving little to do except to read, watch movies in the hotel or at the cinema. Between the books and newspapers I had read, and the movies I had watched in the eighties, there were countless instances of suicide. The reasons varied and included heartbreak, mainly women, but men too; threats from loan sharks; bullying, mostly in Japan back then; and in very few instances, despair so profound that the character needed medical intervention. All the reasons for suicide seemed normal to me. It also seemed normal when no reasons were offered for a particular suicide.