Ashley Hewitt Efficient Music Production: How to Make Better Music, Faster

Published by Stereo Output Limited, company number 11174059

ISBN number 9781999600358

Copyright Ashley Hewitt 2020

Ashley Hewitt has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright holder except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical views and certain other non-commercial uses permitted by copyright law.

Please go to www.stereooutput.com to contact us or follow us on various social media channels.

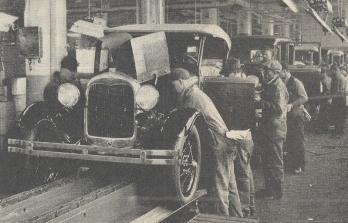

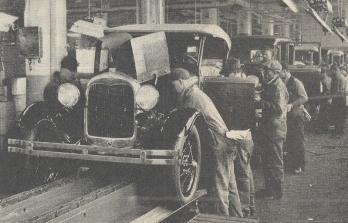

I t was 1913 in Highland Park, Michigan, and Henry Ford had a vision that would change the world forever.

Ford built cars. The Model T, introduced in 1908, was a simple and relatively inexpensive vehicle. It was still beyond the pockets of most consumers however, and cars were generally the preserve of the privileged few. Ford was determined to reverse this trend and build cars for the great multitude .

The average car took over twelve hours to build, and Ford understood that the key to reducing the cost of his cars was to build more of them, for a lower outlay during assembly. The Model T had already begun life based on the idea of efficiency through simplicity. There was only one possible chassis available for example, and Ford had pioneered the use of vanadium steel which was lighter, stronger and cheaper than alternatives available at the time. Now Ford turned his attention to the building process itself.

Ford broke the Model Ts assembly process down into eighty-four discrete steps. He converted his plant workers roles from general engineers who oversaw everything, to specialists who would only oversee a few steps each, the theory being that a specialist in a limited number of tasks would be far more efficient than someone with multiple responsibilities.

He then hired efficiency expert Frederick Winslow Taylor to further analyse each step. One of Taylors key methods was called the time and motion study, in which the average duration of each step was determined and measures then implemented to reduce it.

The cumulative effect of all these small efficiencies was tremendous. It culminated in the streamlined process that became known as the assembly line, in which the cars moved through each of the eighty-four steps on a belt moving at six feet per minute. The efficiency gains of the assembly line had effectively quartered the average time to manufacture one car to around three hours .

I n 1924, Fords ten -millionth Model T rolled off the assembly line and thanks to its innovations and efficiency, Fords dominance in the car market was sealed - for the time being at least. It had allowed Ford to cut prices by half and then half again, from $850 in 1909 to just $290 by 1924.

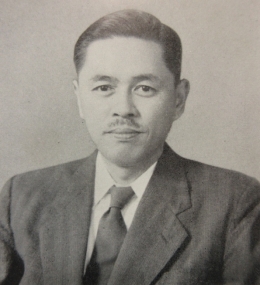

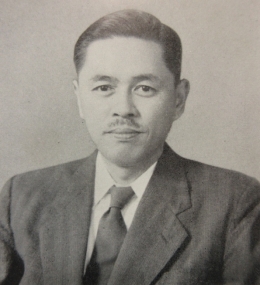

In the early 1950s, Taiichi Ohno also had a vision. Ohno was an executive at Toyotas automotive division, having been brought over from Toyotas fabric manufacturing division to improve productivity and efficiency.

B etween 1945 and 1955 Ohno experimented with many different concepts in production in order to increase efficiency. Rather than follow the mass production system of the US auto industry, Ohno eventually developed a system modelled on the way supermarkets operated, a concept that became known as Just-in-Time .

Toyota was not a wealthy company and could not afford to waste money on excess equipment or materials. They expected the acquisition of materials to happen on time, using the minimum amount of resources required for the task, much as a supermarket re-stocks its shelves with the appropriate amount of products according to customer demand. In Ohnos model, the demand for materials accordingly came from the production workers themselves as needed, rather than from management. Ohnos innovative approach eventually became known as the Toyota Production System.

The four goals of the Toyota Production System were:

1) Provide world class quality and service to the customer.

2) Develop each employees potential.

3) Reduce cost and maximise profit through the elimination of waste (a concept currently known as lean manufacturing).

4) Develop flexible production standards based on market demand.

It is the third goal the minimisation of waste - that we will mainly focus on in this book.

Ohno identified seven types of waste:

1) Correction/scrap this is where products are defective or require repairs.

2) Overproduction this is where too many products are produced, or they are produced too early.

3) Waiting this is where products are delayed for any reason.

4) Conveyance this is the time products spend in transit between areas.

5) Processing this is where more processing of a product takes place than is actually necessary to achieve the desired result.

6) Inventory this is where products and parts sit idle.

7) Motion this is wasted movement, such as unnecessary turning, lifting and reaching.

Implementing the Toyota Production System helped Toyotas automotive division expand rapidly. In 1957, the Toyota Crown became the first Japanese car exported to the United States. Toyotas growth has since gone from strength to strength, and Toyota is now the worlds dominant car manufacturer, with over 9% of the global market. The Toyota Production system still plays a key role in this ascendance.

Now, you may be wondering about the relevance of these two stories. Youre just a producer in your studio, trying to make some good music. You may even feel slightly uncomfortable with the premise of applying industrial philosophy to such a pure art form, viewing the whole concept of manufacturing as somewhat de-humanising. Its all a matter of scale however. Car manufacturers mass-produce products on billion-dollar budgets, but at core, their challenges are remarkably similar to your own.

Your time is precious. You might be a professional musician fighting to compete against the thousands of tracks that enter the music market every single day, or you may be an amateur or semi-professional delicately balancing your love of music production against the needs of your family and a time-consuming day job. Either way, your valuable time is your most limited resource, and using it correctly is key to making a success of your work.

This book contains a collection of ideas drawn from many different sources. Here you will find a wealth of advice ranging from simple studio workflow tips, to novel ways to think about your music production approach itself. It is hoped that you will approach these concepts with an open mind and open heart, because over a sufficiently long timeline the smallest gains will translate to vast improvements in your workflow and ultimately your own creativity.

Next page