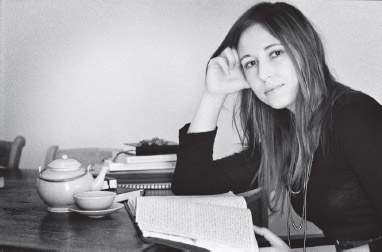

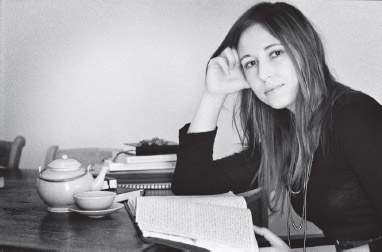

Alice Nelson is an Australian writer. Her first novel, The Last Sky, was shortlisted for The Australian/Vogels Literary Award, won the T.A.G. Hungerford Award and was shortlisted for the Australian Society of Authors Barbara Jefferis Award. She was named Best Young Australian Novelist of 2009 in the Sydney Morning Heralds national awards program. Alice works as a freelance journalist and teaches creative writing. She is currently completing her doctorate in the School of English and Cultural Studies at the University of Western Australia.

First published 2015 by

FREMANTLE PRESS

25 Quarry Street, Fremantle 6160

(PO Box 158, North Fremantle 6159)

Western Australia

www.fremantlepress.com.au

Also available in a paperback edition.

Copyright Alice Nelson, 2015

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Enquiries should be made to the publisher.

Consultant editor: Naama Amram

Cover design: Nada Backovic

Typesetting: Karmen Lee

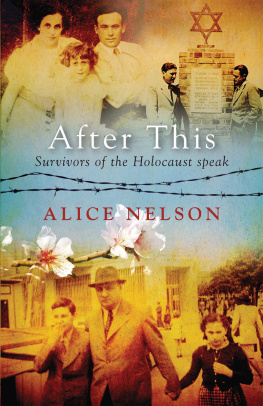

Front cover photographs (clockwise from top left): Rosa Levy with parents; Heiny Ellert (right) at Feldafing displaced persons camp; Kurt Ehrenfeld with father and sister in 1943.

Cover images: background texture Boonsom/Shutterstock; background texture David M. Schrader/Shutterstock; blossom Feblacal/Dreamstime.com; barbed wire Tshanahans/Dreamstime.com.

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Nelson, Alice, 1980 author.

After this : survivors of the Holocaust speak / Alice Nelson.

9781925162370 (ebook)

Holocaust, Jewish (19391945)

Holocaust, Jewish (19391945)Personal narratives, Australian.

Holocaust survivorsAustraliaBiography.

940.5318092

Fremantle Press is supported by the State Government through the Department of Culture and the Arts.

Publication of this title was assisted by the Commonwealth Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body.

Contents

Foreword

These life-stories are extraordinary. The telling is straightforward. There is no artifice, no embroidery. Each narrative is a recounting of specific events set in specific places, told matter-of-factly. The facts speak for themselves. The cumulative effect is riveting. It is a mitzvah these eyewitness accounts have been assembled and put between the covers. Made solid. The darkness made visible.

I am of the second generation. As a child I heard anecdotes, fragments of family stories, gazed at photos of grandparents, uncles and aunts, cousins, scenes of my parents home-city of Bialystok and its surrounding towns and villages. The prewar photos were haunting, as are the prewar photos that accompany the stories in this anthology. The images are rescued from oblivion. They add immeasurably to the telling. It was a wise decision to publish them.

My parents, and many of their generation, split their lives between two periods: before the war and after the war. So it is with these accounts. Each tale unfolds as a three-act drama. Act one is set in the time before: Once upon a time I had a home, a family. A mother, a father, brothers and sisters, a circle of friends, extended family. Once I had a life, a community, and a sense of belonging.

Then all is overturned. Ruptured. For some, the second act is a drawn-out process of accumulating horrors. It may include years of slave labour, incarceration in a succession of ghettoes, concentration camps, countless acts of cruelty. For others the second act begins abruptly with a knock on the door, a herding into the streets, a trek to the railway station, deportation to death camps. For all, it is a descent into hell.

Act two ends at the moment of liberation. But the impact endures. Prewar life has been shattered. Freedom is coupled with a sense of devastation. Emptiness. Accompanied by confirmation of the death of loved ones. Survivors return to homes occupied by others, to decimated communities. Hence, act three begins in uncertainty, a state of limbo, with time spent in displaced persons camps, journeys to new worlds, to the ends of the earth, to Perth, distant Melbourne. It encompasses years of rebuilding, creating new lives, raising families.

New photos appear, family portraits snapped at gatherings and weddings. Images of rebirth, new links in severed family chains forged through hard work and a ferocious determination. The memories and trauma, however, cannot be suppressed. The survivors stories invariably emerge after years of silence, maintained to protect their children from the horrors, or because their experiences seem so out of place in the bright light of the new world. In many cases, it is only the urgent request of children grown to adulthood that prises open the Pandoras box.

In time, the reluctant narrators begin to see a deeper purpose. They embody history. They are eyewitnesses. And they bear witness. Some begin to address schools, the public, and become guides into the Kingdom of Darkness. The Holocaust Institute of Western Australia, its scribes and volunteer interviewers, and Alice Nelson, act as midwives, facilitating the rebirth of suppressed memory.

These accounts, when read in total, represent collective wisdom. They have much to say about love, hatred, trauma, betrayal, endurance, the randomness of fate, the pain of separation, the extremes of human brutality and perversion. And, in some instances, they touch upon unexpected kindnesses, enacted by those who risked their lives to save a fellow human being. As one writer says, in response to a life-saving act by a stranger: It was the first time I had experienced that there were good people in the world.

These accounts, however, do not offer an easy way out. The trauma, the tragedy and the brutality are not diminished, not sanitised. The horrors are named and documented. They are not made more palatable. We are compelled to listen.

I leave the final word to one of the narrators. It is typically direct and prosaic: The Holocaust is a monumental part of history, so please do not forget what I am saying. I wont be here forever to tell the story. It is in your hands and the hands of your generation and generations to come to always remember.

Arnold Zable

Introductory essay

On the front page of my husbands family photograph album is the black-and-white image of an old Polish rabbi. This man, with his dark eyes, his full beard and his extraordinary prescience, saved my husbands grandfather from a terrible fate by convincing him to leave Poland and arranging passage out of the country before it was too late to leave. All of those who came after in my husbands family owe their lives to this scholarly rabbi all the Australian and Israeli and American descendants, my own husband, the two strapping boys who clomp down the hallways of our home on the quiet shores of Australia, and the children that they themselves might one day have.

Next page