Copyright 2012 by Caroline Stoessinger

Foreword copyright 2012 by the Estate of Vaclav Havel

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Spiegel & Grau, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

S PIEGEL & G RAU and design is a registered trademark of Random House, Inc.

Photographs, excluding the frontispiece, are by Yuri Dojc and are reprinted by permission of the photographer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Stoessinger, Caroline.

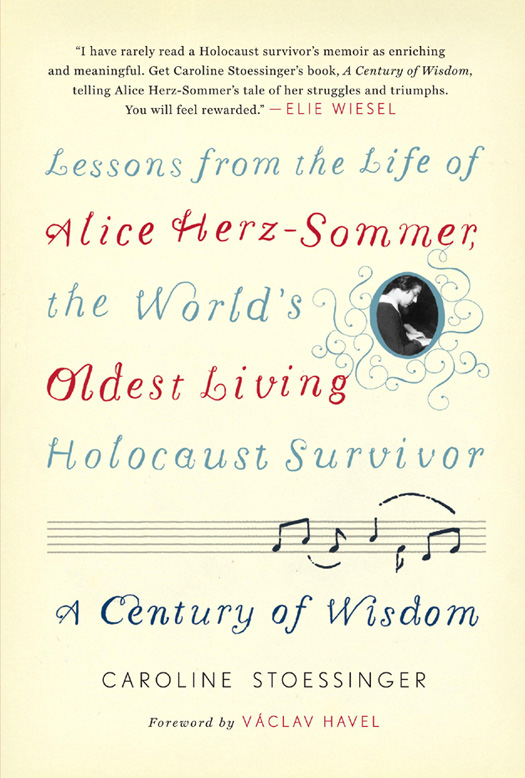

A century of wisdom: lessons from the life of Alice Herz-Sommer, the worlds oldest living Holocaust survivor / Caroline Stoessinger.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-679-64401-9

1. Herz-Sommer, Alice, 1903 2. JewsCzech RepublicPrague

Biography. 3. Women pianistsBiography. 4. Theresienstadt

(Concentration camp). 5. Holocaust survivorsIsraelBiography. 6.

Holocaust survivorsEnglandLondonBiography. 7. Prague (Czech

Republic)Biography. I. Title.

DS135.C97H488 2012

940.5318092dc23 [B] 2011035168

www.spiegelandgrau.com

v3.1

No longer forward nor behind

I look in hope or fear,

But, grateful, take the good I find,

The best of now and here.

John Greenleaf Whittier, 1859

FOREWORD

Vclav Havel

A Century of Wisdom is a deeply moving account of the epic journey of one woman who has crossed decades and national borders to defy death and to inspire us all. Set against both the beauty of our Central European culture and the tragic events of the twentieth century that shut Czechoslovakia off from the rest of the world for nearly fifty years, Alice Herz-Sommers life illustrates a deep ethical and spiritual strength. Her memories are our memories. Through her suffering we recall our darkest hours. Through her example we rise to find the best in ourselves.

At 108 years old, Alice enjoys telling stories from the lives of great thinkersfrom Gustav Mahler to Sigmund Freud and Viktor Frankl, from Martin Buber to Leo Baeckwho have left an indelible impression. With her musicas a concert pianist and as a teachershe has influenced countless students, their children, and their childrens children, just as she comforted her fellow inmates in the Theresienstadt concentration camp with her talents. Since the war, Alice has been equal parts teacher and student; she has spent the balance of her life in untiring pursuit of knowledge and understanding of who we are as humans, as a community, and as individuals.

Alice has said, I never give up hope. This sentiment resonates strongly with me, for I believe that hope is related to the very feeling that life has meaning, and as long as we feel that it does, we have a reason to live. Alices irrepressible optimism inspires me. She has survived, I believe, so that the world may know her story, our story, of truth and beauty in the face of evil. Not only can we learn from Alice today but future generations can take wisdom and hope from her richly textured life.

CONTENTS

PRELUDE

At 108 years old, Alice is the worlds oldest Holocaust survivor, as well as the worlds oldest concert pianist. An eyewitness to the entire last century and the first decade of this one, she has seen it allthe best and the worst of mankind. She has lived her life against a backdrop of good amid the chaos of evil, yet she continues to throw her head back in laughter with the same optimism she had as a child.

Despite her years of imprisonment in the Theresienstadt concentration camp and the murders of her mother, husband, and friends at the hands of the Nazis, Alice is victorious in her ability to move on and to live each day in the present. She has wasted no time on bitterness toward her oppressors and the executioners of her family. Aware that hatred eats the soul of the hater rather than the hated, Alice reasons, I am still grateful for life. Life is a present. A Century of Wisdom tells of one womans lifelong determinationin the face of some of the worst ills and heartachesto bring good to the world. In Alices story we can find lessons for our own twenty-first-century lives. This is Alices gift to us.

Her name, Herz-Sommer, means heart of summer, although she was born on a bitterly cold day, November 26, 1903, in Prague. Her parents, Friedrich and Sofie Herz, called her Alice, which means of the noble kind. Her father was a successful merchant, and her mother was highly educated and moved in circles of well-known artists and writers that included Gustav Mahler, Rainer Maria Rilke, Thomas Mann, Stefan Zweig, and Franz Kafka.

Alice grew up in a secure and peaceful environment, in which reading and concertgoing were the major forms of entertainment; neighbors would help one another in times of sickness; and families could calculate their interest and retirement for many years to come. Before World War II, Alice was well on her way to a distinguished career as a concert pianist. Her mothers profound love and deep knowledge of music as well as her friendship with Mahler provided Alice with inspiration, and she decided to become a pianist at an early age. Alice remembers accompanying her mother by train to Vienna two days before her fourth birthday to hear Mahler conduct the farewell performance of his Second Symphony with the Hofoper Orchestra on November 24, 1907. Alice said that after the concert her mother talked with the composer, and then I spoke a little bit with Gustav Mahler. Alice tucks in her lips and raises her shoulders in her expression of wonder at that moment in the presence of genius. Most likely Alice was with her mother when Sofie, together with Arnold Schoenberg, stood in the crowd at the railroad station to wave as Mahlers train slowly left Vienna the morning after the concert.

Years later, after auditioning for Artur Schnabel, she was convinced that a career as a pianist was within her reach. Frequently she was the featured piano soloist with the Czech Philharmonic, and she completed a number of commercial recordings, receiving glowing reviews in Prager Tagblatt, the German paper in Prague, from Max Brod, Kafkas friend and biographer.

But the world around Alice had gone mad. Czech laws were abolished. The city was deluged with Nazi flags. Alice snapped a photograph of her three-year-old child standing in front of a sign that read JUDEN EINTRITT VERBOTEN (Jews are forbidden to enter) and barred his entrance from his favorite park. After the Anschluss, in March 1938, Alices sisters and their families began making frantic preparations to immigrate to Palestine; Alice and her husband chose to stay behind with their young son to care for her aging mother, who would be one of the first to be sent to Theresienstadt. Instinctively Alice understood that she would never see her mother again as she watched her trudge with her heavy rucksack into an enormous building the Nazis had confiscated to use for a human collection center. Where they burn books, they will ultimately burn people also, Heinrich Heine had cautioned a century earlier. Still, most people did not believe the dire predictions.