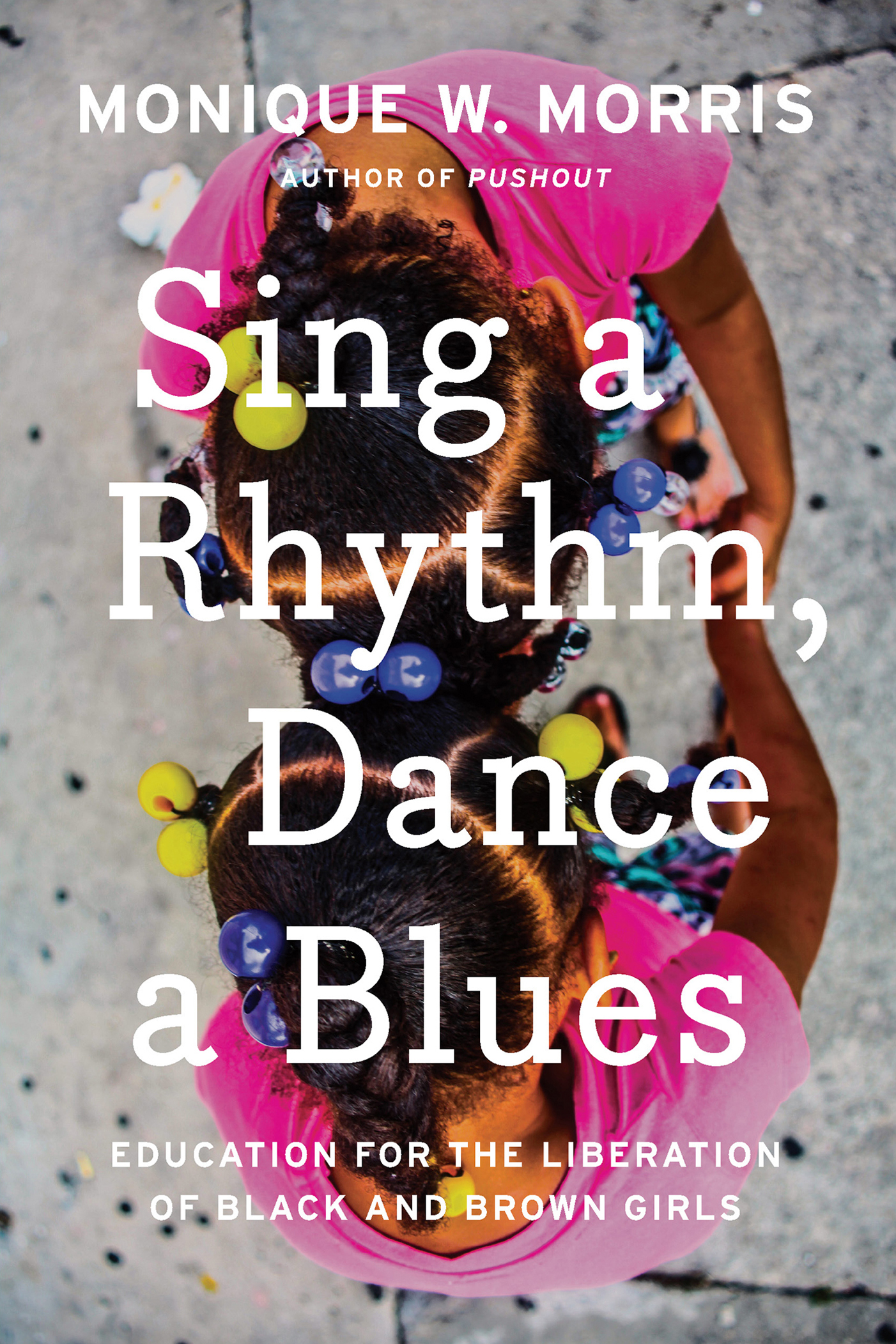

Sing a Rhythm, Dance a Blues

Also by Monique W. Morris

Pushout: The Criminalization of Black Girls in Schools

Black Stats: African Americans by the Numbers in the Twenty-First Century

Too Beautiful for Words: A Novel

SING A RHYTHM, DANCE A BLUES

EDUCATION FOR THE LIBERATION OF BLACK AND BROWN GIRLS

Monique W. Morris

For Black and Brown girls

and the people who cherish them

Schools can therefore be seen as the most powerful alternative to jails and prisons. Unless the current structures of violence are eliminated from schools in impoverished communities of colorincluding the presence of armed security guards and policeand unless schools become places that encourage the joy of learning, these schools will remain the major conduits to prisons. The alternative would be to transform schools into vehicles for decarceration.

Angela Y. Davis

Contents

Prelude

Everything, everything, everything gon be alright, Oh yeah.

When I was a little girl,

Only twelve years old,

I couldnt do nothing

To save my dog-gone soul.

My mama told me

The day I was grown,

She says, Sing the blues, child,

Sing it from now on.

Im a woman, oh yeah.

Im a woman, Im a ball of fire.

Im a woman, I can make love to a crocodile.

Im a woman, I can sing the blues.

Im a woman, I can change old to new.

Spelled w-o-m-a-n.

Ellas McDaniel (Bo Diddley) and Koko Taylor, Im a Woman (Alligator Records, 1978)

Introduction

Blue Moments

somebody/anybody

sing a black girls song

bring her out

to know herself

to know you

but sing her rhythms

carin / struggle / hard times

sing her song of life

Ntozake Shange, Dark Phrases, For Colored

Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the

Rainbow Is Enuf

O akland, California, July 2018.

In the distance, we can hear a woman wail a gutwrenching cry that sings of a trauma so severe, all of us can feel its effects. It pierces our souls. Her cry, while heartbreaking, is melodic. Her public display of grief is both intriguing and healing.

Thats my baby girl up there, Ansar Muhammad said to The shock and sorrow in his eyes were paralyzing.

He was speaking of his daughter, eighteen-year-old Nia Wilson, who, along with her sister Lehtifa, was stabbed in an act of unprovoked hate by John Cowell on a BART train one night. Lehtifa suffered serious injuries to the neck. She survived, but her sister did not.

I want justice for my daughter, her father said.

Justice for Nia. Her name means purpose in Swahili.

Justice for Lehtifa. Her name means gentle in Arabic.

Justice for girls who are the targets of violence, physical and otherwise. Justice for their purpose, justice for their gentle futures. The fatal stabbing of Nia Wilson, a high school student, occurred at the intersection between racism and gender-based violence, neither of which is random or unintended.

This volatile intersection leaves Black girls relatively unprotected from the pattern of violence that they experience in public and in private at the hands of strangers and those they love. This vulnerability opens a door for others to treat their marginalization as a creation of Black girls own making, their truths obscured as entertainment.

Following her death, people of the Oakland community cried for Nia. They danced for her. They mourned her through altars and chants of Say her name.

We all sang a blues.

A grainy, black-and-white video of Billie Holiday singing Strange Fruit offers a meditation on the redemptive poten tial of the blues. In the video, Ms. Holiday stands in a glittery sweater dress, alone in the frame as a singular point of interest in the narrative about the heinous violence that surrounded her. Her long black hair is pulled into a ponytail, earrings dangle delicately beside her neck, falling just above her shoulders. Her interpretation of this blues classic that emerged from a lynching protest poem penned by Abel Meeropol was as fragile as Black Americas grasp on justice. But it was also resilient. It was not just the words; it was her physical reading, her attitude while singing, that bestowed the greatest gifts.

Southern trees bear strange fruit

(She wrinkles her brow and slightly frowns as her lips form the words.)

Black bodies swinging

(She cocks her head, and then lingers in a distant stare.)

Here is fruit for the crows to pluck

(She blinks slowly and leans forward slightly while maintaining a frown.)

Nia Wilsons body joined the panoply of strange fruit that unfortunately shape our memory and understanding of just how much Black lives matter in our racialized nation.

Its all so instructive. Upsetting. Liberating.

Angela Davis once described Strange Fruit as one of the most influential and profound examplesand continuing sitesof the intersection of music and social consciousness. By disrupting the landscape of material [Billie Holiday] had performed prior to integrating Strange Fruit into her repertoire, she reaffirmed among her musical colleagues the import

Billie Holiday, using the instruments of her body, was tuning us into the frequencies of timeless ancestral truths that aggravate and settle the soul. She was singing the blues while challenging us to do better. She was in service as she was serving. Audre Lorde noted that Black women are expected to use our anger only in the service of other peoples salvation or learning. But that time is over. Indeed, the anger and pain experienced by Blackand Brownwomen and girls must also serve their own liberation.

More than a conduit for marginalized voices, the blues is a means to stimulate radical possibilities.

The blues emerged in the nineteenth century as an African American musical genre rooted in the phrasing of Negro spirituals, the work songs of enslaved, impoverished people and the cultural shouts and hollers that traditionally express sorrow, betrayal, and harm. But the blues was also an underground musical railroad to survival. While typically associated with the articulation of pain and revenge, the blues is also about becoming. In some cases, the expression is about a longing for freedom. Though associated with men, the blues has also been a destination for women seeking to articulate their truths, particularly as an expression of the racialized gender bias shaping their lives. Billie Holiday, Bessie Smith, Gertrude Ma Rainey, Big Mama Thornton, Koko Taylor, and others who would later weave their blueprints into rock and roll, rhythm and blues, country, and funk understood that their freedom could be accessed through their wails, moans, and dances. Millions of people consume the blues as entertainment without acknowledging its most important contributions to the freedom struggle: a platform for truth telling, a form of resistance, and thus a pathway to healing and learning.

Next page