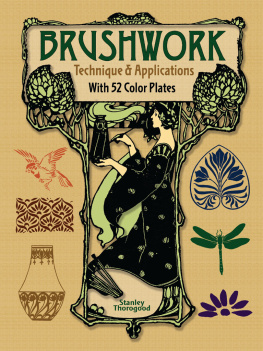

BRUSHWORK

Technique & Applications

With 52 Color Plates

BRUSHWORK

Technique & Applications

With 52 Color Plates

Stanley Thorogood

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC.

Mineola, New York

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 2015, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published by George Philip and Son, London, in 1907 under the title The Manipulation of the Brush as Applied to Design: A Course of Brushwork for Elementary and Secondary Schools, 4th edition, revised and enlarged.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Thorogood, Stanley, 18731953.

[Manipulation of the brush as applied to design]

Brushwork technique and applications : with 52 color plates / Stanley Thorogood.

pages cm.

eISBN-13: 978-0-486-80583-2

1. Brushwork. I. George Philip & Son. II. Title.

ND1505.T48 2015

751.4dc23

2014049005

Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation

79732501 2015

www.doverpublications.com

CONTENTS.

PLATES.

| . | Various Brush Strokes applied to Patterns. |

| . | Types of Natural and Conventional Forms drawn with the Brush. |

| . | Designs drawn with the Brush. |

| . | The Use of the Brush in suggesting ideas. |

| . | Decoration of Vase Forms. |

| . | Direct Freehand Drawing and Application. |

| . | Direct Designing on given Lines. |

| . | Historic Brushwork Examples. |

| . | Sketching direct from Plant Life. |

| . | Mass Drawing of Common Objects direct with the Brush. |

PREFACE.

T HE educational value of the use of the brush as a means of expressing form, and training the hand and eye, is gradually being recognised by educational authorities throughout the country.

I have compiled a few notes and illustrations that may be a guide to Teachers introducing the subject in Elementary and Secondary Schools, and Art Classes. No attempt has been made to arrange the work in progressive stages, as the drawings are not intended to serve as mere exercises or illustrations of design for scholars, but rather as a text-book on the subject of Brush Drawing for Teachers, showing different methods of interpretation, together with Historic examples.

In many instances the drawings illustrated are mere impressions sketched spontaneously with the brush as one would with a pencil, and are purposely left in that state to show how, in some cases, the brush should be used to sketch out IDEAS only (see ). Accuracy of drawing and detail must be the chief aim when working out the finished drawing.

Such exercise with the brush will be found invaluable, in order to apply it to practical use in designing and sketching from Nature.

It is a most difficult task to arrange Brush Drawing exercises in progressive stages, and experience teaches one that it is almost unwise to make the attempt.

In the case of the more advanced patterns or naturalistic studies it is impracticable. In many instances it would be impossible to state which particular example would present the greatest difficulty to the student. The chief aim in the lower classes should be to master the manipulation of simple strokes and the drawing of leaves, vegetable forms, and simple common objects, in silhouette.

A few photographs taken from the actual work of children attending Elementary Schools, ages varying from 5 to 13 years, have been added to illustrate the various stages of work from the lowest to the highest classes, both in Brush Drawing and Freehand and Application.

STANLEY THOROGOOD.

The Manipulation of the Brush as applied to Design.

M R . R USKIN , in his Oxford lecture on Line, says:

The fact is that, while we have always learned, or tried to learn, to paint by drawing, the ancients learned to draw by painting. The brush was put into their hands when they were children, and they were forced to draw with that until, if they used the pen or crayon, they used them with the lightness of a brush or the decision of a graver.

The use of the brush, hand-in-hand with the pencil, is rapidly being recognised as an important medium for use in a childs early artistic training, and is advocated by the leading craftsmen and artists of the day.

It is only fair to the children in our public schools that those showing ability should have every opportunity of developing their powers, and that they should be taught drawing in such a manner that it may form a stepping-stone to higher work when passing on to local Schools of Art. The importance of teaching children to use the wrist and arm in drawing, to sit well back from their work, and to draw in a free style, cannot be over-estimated for any good Art work. Students doing advanced work in Schools of Art have to accustom themselves to work from an easel, and it will be seen how important it is that this principle should be insisted on in the most elementary stages of work, whether drawing with the brush or pencil.

The scheme for drawing in Elementary Schools, as shown in the Alternative Syllabus of the Science and Art Department, is an excellent one, and it would be well if its principles were carried out in detail in every school.

It is necessary that cleanliness and good quality of line should be observed ; but it is to be feared in the past that success has depended on the result of making the pencil do the work of a pen, instead of insisting, first and foremost, on good proportion and consideration of masses. From the very first, children should be taught to see the value of this; and for this purpose the introduction of brush and colour work is an excellent one. The early application of drawing to pattern-making, the tinting in of masses by means of coloured chalks and water colour, together with the use of the brush, as practised in a number of our large public schools, is a step in the right direction, for this work should go hand-in-hand with drawing. One can fully realize how such a subject as brushwork must be looked upon by teachers and others who have only regarded it in a superficial way; but those with a knowledge of drawing, if they study the effect of the brush, will soon see how by practice they can become somewhat dexterous in the handling, and will, at the same time, learn what results can be produced by the brush that the pencil could not give.

By using the brush, greater freedom of hand is acquired, while it is capable of developing powers of drawing beyond any other means. It forms a direct means of expressing mass and space, as well as line: it consequently assists the student to more rapidly appreciate the value of quantities, by directing his attention to spacing and to the solidity of the forms used. It is invaluable for training scholars to use the wrist and arm in drawing ; in fact, it is in this teaching of handling and manipulation that the value lies in its use. Good results are the outcome of practice. To wield a brush with freedom requires a great amount of exercise and care. It is such a flexible tool, that, by varying the pressure, forms without number can be made ; and it will be found that by it shapes can often be suggested that no other tool could possibly give.