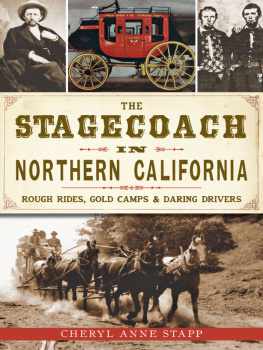

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2014 by Cheryl Anne Stapp

All rights reserved

First published 2014

e-book edition 2014

ISBN 978.1.62584.732.4

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Stapp, Cheryl Anne.

The stagecoach in Northern California : rough rides, gold camps & daring drivers / Cheryl Anne Stapp.

pages cm

print edition ISBN 978-1-62619-254-6 (paperback)

1. Stagecoach lines--California, Northern--History. 2. Stagecoaches--California, Northern--History. 3. Frontier and pioneer life--California, Northern. 4. California, Northern--History--19th century. I. Title.

HE5748.C2S74 2014

388.32--dc23

2014017910

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

For Murry

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Researching the times and lives of the individuals who made the stagecoach an enduring icon of Californias gold rush history has been fascinating, and I am indebted to the written accounts of observers who lived in the nineteenth century, as well as the works of modern historians. I wish to thank the dedicated professionals and other enthusiasts who helped me find a specific document or interesting story: the marvelous librarians at the California State Library, Sacramento, and staff members at the Placer County Archives, the Shasta County Historical Society and the Amador County Chamber of Commerce. Special thanks go to Dr. Kenneth Umbach for his invaluable assistance and to Allen Rountree, a wonderfully wise docent at the Sunnyvale Museum.

PART I

WESTERN STAGING BEGINS

California had no public transportation before 1849. Overland wayfarers rode their own, or borrowed, horses and mules. Families visited relatives in plodding oxen-powered carretas, simple carts with wheels hewn from solid slices of tree trunks.

Passersby who stopped for a nights rest at isolated ranches were entrusted to deliver letter mail to destinations along their expected routes. If no sojourner materialized, ranchers and town merchants pressed an employee into service as a mounted courier. When necessary or more expedient, private watercraft took small numbers of passengers over the rivers. For the most partuntil their peace was shattered in the summer of 1846 by the Mexican-American Warresidents of sparsely populated California, a half-neglected province of Mexico, lived their lives at a leisurely pace.

Everything changed with two near-simultaneous events in early 1848: gold was discovered in the Sierra Nevada foothills, and a week later the Treaty of Guadalupe Hildago that ended the Mexican-American War ceded California to the United States. The treaty was not announced until July, after it had been ratified by both governments. By then, however, upward of four thousand bedazzled gold prospectors from various Pacific Coast regions were working the streams and ravines. The following year, tens of thousands of gold seekers from all over the world swarmed into northern California by land and sea.

Before the stagecoach, those arriving by sea walked forty miles and more to the gold fields from inland river landings.

The volume of mail in the hulls of incoming ships increased a thousand fold, and lonely miners in isolated camps clamored for delivery of letters from loved ones back home. Successful prospectors needed reliable conveyance of their freshly mined gold to bankers safes down in the valleys and coastal towns, which were suddenly teeming with individuals of diverse skills who had come to exploit ground-floor economic and political opportunities. Before the stagecoach tied them all together, the exchange of news and commerce between mining districts and far-apart settlements was confined to mule teams, lumbering wagons and just two navigable rivers.

Alexander Todd, a luckless but enterprising young miner, is generally credited with being the first to establish a mail and express service in 1849when there was no official postal delivery providedbetween the San Francisco post office and the mining camps. He went from camp to camp soliciting subscribers, who gladly paid him one dollar apiece to list their names and an additional ounce of gold for each letter he brought them. He used surefooted pack mules and was so successful at delivering mail that miners and merchants alike asked him to carry their gold dust for deposit in San Francisco vaults. Todd purchased a rowboat to accommodate his increased cargoes, wending down the San Joaquin River and across San Francisco Bay. At the seaport, there were always men anxious to get to the mining districts, and Todd allowed passengers, charging each man a sixteen-dollar tax for the privilege of rowing his boat. The number of men he could take on any one trip was limited, and rowing upriverespecially in bad weatherusually wasnt fast.

Speed was the new imperativefor communication between sprouting civic centers and to transport shiploads of excited fortune-seekers who were in a hurry to reach the gold fields. Speed was the urgent need, but also welcome was the shelter from the elements that a stagecoach could provide. The iconic image of a rumbling Wells Fargo stagecoach drawn by six galloping horses has become the modern symbol of staging in the Old West, but Wells Fargo wasnt the first in gold-fevered California, and the company didnt own any stagecoaches until years after the gold rush ended.

Historians are divided in their opinions over who, between two primary candidates, established the first stage line in California: John Whisman or James E. Birch. Both started up in 1849 with borrowed, dilapidated equipment and fidgety horses; both charged a thirty-two-dollar fare. Whisman founded a fifty-mile stage service between San Francisco and San Jose. Birch founded stage transport from Sacramento to the gold-rich settlements of Coloma and Mormon Island in the Sierra foothills, ten miles shorter than Whismans route but over steeper and rougher ground.

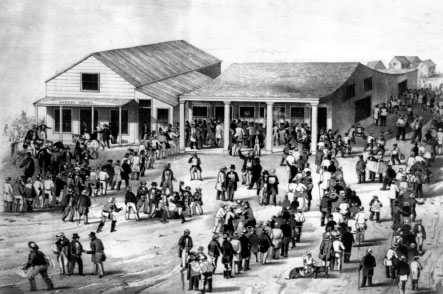

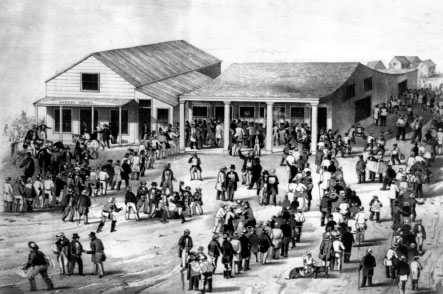

Crowds at the San Francisco Post Office in the 1850s, anxious for news from home. Library of Congress, from a lithograph by William Endicott & Co.

The claim for Whisman is based solely on the reminiscences of one of his drivers, Henry Ward. Ward stated that John Whisman was the first stage operator in this part of Californiain the fall of 1849without specifying the month. An advertisement in Sacramentos Placer Times confirms that James Birch was already in the staging business there before the end of July. Both are bested for first place by this June 28, 1849 advertisement in the Weekly Alta California:

MAURISON & COMPANYS EXPRESS AND MAIL LINE. The undersigned would respectfully inform the public that they have established a line of Stages between Stockton and the Stanislaus Mines, for the accommodation of passengers and baggage. A stage will leave Stockton every other day for the mines, at 4 oclock, A.M., and arrive at the other end of the route in 12 hours. Returning, a Stage will leave the mines at the same hour on the intermediate days, and arrive at Stockton at 4 oclock, P.M

Next page