Railroads Past & Present

GEORGE M. SMERK, EDITOR

A list of books in the series appears at the end of this volume.

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

601 North Morton Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47404-3797 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

Telephone orders 800-842-6796

Fax orders 812-855-7931

2013 by John H. White Jr.

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

Manufactured in the

United States of America

Library of Congress

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

White, John H., [date]

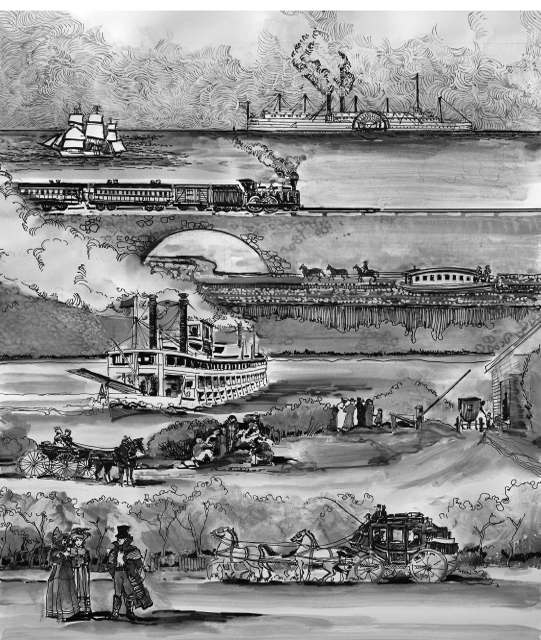

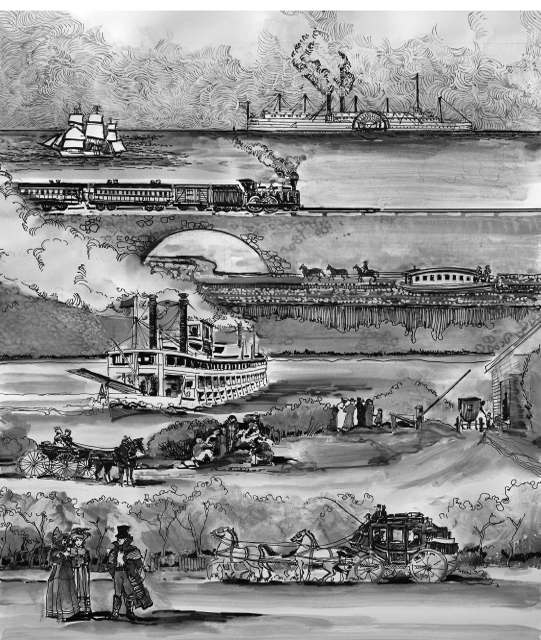

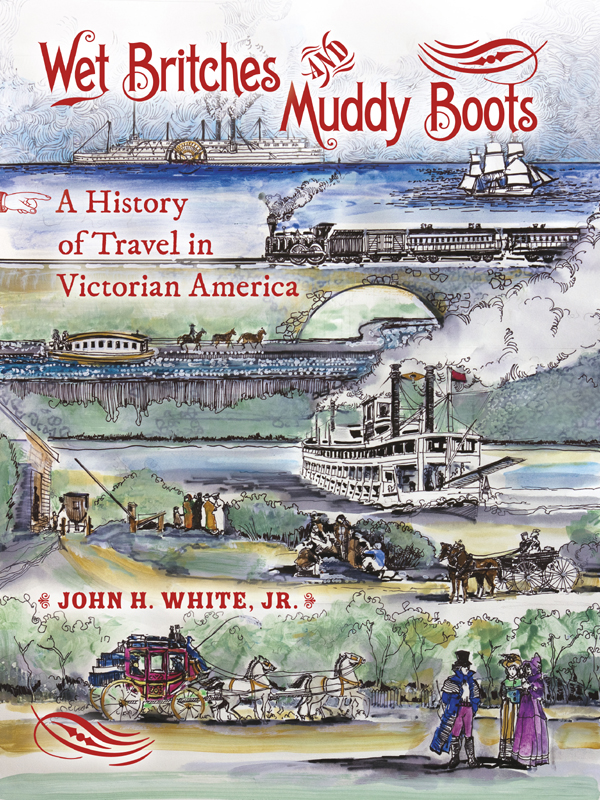

Wet britches and muddy boots : a history of travel in Victorian America / John H. White, Jr.

p. cm. (Railroads past and present)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-253-35696-3 (cl : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-253-00558-8 (ebook) 1. Travel United States History 19th century. 2. Transportation United States History 19th century. I. Title.

HE203.W45 2012

388.0973'09034 dc23

2011044593

1 2 3 4 5 18 17 16 15 14 13

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF CHRISTINE.

Foreword

ONE OF THE MOST ARRESTING IMAGES IN THE HBO ADAPTATION of David McCullough's best-selling biography of John Adams is the departure of the president from Washington, D.C., in March 1801. A huge horse-drawn coach pulls up in front of the White House. With some difficulty, the sixty-seven-year-old Adams climbs onto it, taking a seat among a group of ordinary Americans. Then the coach pulls away, launching Adams on his long journey back to his home in Quincy, Massachusetts.

The scene startled me because it was so unfamiliar. I knew I could hold forth at length on why Adams was leaving Washington against his will and the significance of his mingling with his fellow citizens. But I had no idea what this form of public transportation was, how long it had been in operation, how much it cost, how long it took to get from one place to another, and what it felt like. Like most of my academic peers, I was so used to thinking about large-scale questions of power and change that I had virtually no idea of what it was like to get around in the United States in 1800. It quickly dawned on me, of course, that I had just experienced the gap between the kind of knowledge constructed by academic specialists and the kind of knowledge most people want to know. The latter included the details of the Adams's family life, especially the relationship between John and Abigail, which had made McCullough's book so popular. It is, after all, the specifics of what we call material culture the sights, sounds, and texture of ordinary life that most satisfies a human curiosity about the concrete and personal aspects of the past.

When John Adams left Washington, most human beings traveled as their ancestors had traveled for centuries. They walked. But as the coach he boarded suggested, ordinary people were slowly joining the powerful and privileged in being carried, either by other people or by animals. The major exception to this rule was waterborne commerce. Then suddenly in the space of a couple of generations everything changed. The development of steam engines, telegraphs, railroads, and steel made it easier and cheaper to move people, goods, and ideas over long distances and to congregate in rapidly expanding urban areas. The new technology also made it possible for Europeans and North Americans to fight more wars, conquer more territory, and dominate much of the rest of the world. The pace of progress was astonishing, even in retrospect. The United States was a loose confederation of states in 1800, most of them hugging the Atlantic Ocean as they had as British colonies. By 1900, Americans had supposedly settled all of the inhabitable land within the borders of the present-day United States. The continental republic was an industrial behemoth poised to pass Great Britain as the world's greatest economic power, its great cities sprawling concentrations of people, wealth, information, and power.

None of this change would have been possible at least not in the same way without the sudden ubiquity of relatively cheap forms of transportation, not only from coast to coast, mines to factories, fields to markets, but also from suburbs to cities and workplaces to homes. A new breed of capitalist entrepreneurs rushed to exploit these developments, setting up streetcar companies and railroad corporations that would redefine American life and rearrange the structures of power in local communities as well as the nation as a whole. In the early twentieth century there were no greater incarnations of the wonders of modernity than Grand Central Station in New York City and Victoria and Waterloo in London or the traveling palaces of Pullman cars and Cunard liners. Journeys that had once taken weeks, if not months, were accomplished in days or even hours.

The technological revolution had enormous and largely unanticipated social and political consequences. Almost overnight the possibility of a daily commute accelerated the rearrangement of burgeoning urban landscapes into distinctive neighborhoods defined by class, ethnicity, and race, widening the difference between workplace and home and accentuating the separation between family and commercialized leisure. The same men and women who traveled several miles to work every day were also able to attend baseball games, visit amusement parks, and go to the theater. By the second half of the 1800s, trains and steamers encouraged Americans to travel to distant places as merchants, sailors, missionaries, and increasingly as tourists. They went to places famous for their culture (Italy), power (Great Britain), spirituality (the Holy Land), or natural beauty (Niagara Falls). Americans traveled in such large numbers that Mark Twain's 1869 satire, Innocents Abroad, became a runaway best seller.

Americans were not alone. Around the world people were dealing with the impact of railroads and telegraphs, repeating rifles and photographs, sewing machines and steamships. Improvements in transportation and communication made men and women more directly aware of cultural, religious, and political differences. Unexpectedly, they also promoted a convergence in customs. From Shanghai to Boston, people were wearing dark suits, ties, bowler and stovepipe hats, or the latest Paris dresses and bonnets; eating beef and pork, breads and rice; drinking coffee and tea sweetened with sugar; speaking standardized languages; living in cities that in terms of appearance and organization were variations on a global theme; and finding refuge from dirty, crowded public streets in the domesticity of elaborately decorated private homes. Writing of the Young American in 1859, Abraham Lincoln remarked on the interconnectedness and homogeneity produced by a revolution in transportation:

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.