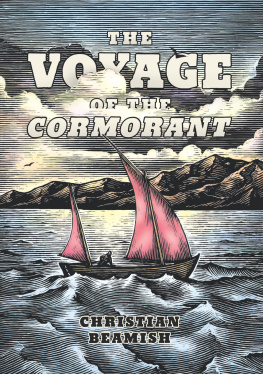

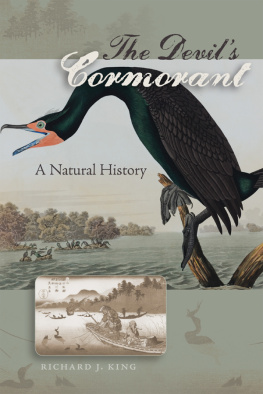

The Voyage of the Cormorant

Christian Beamish

CHAPTER 1

SHAKEDOWN

The fishermen sorted their meager catch on the beach in their workboats the ubiquitous pangas of Baja California. There were four men, two in each boat, and they used a rusted out truck with threadbare tires to drag the vessels from the surf. I left my station wagon also well on its way to rusting through with my boat and trailer on the bluff and went down to where they were working.

As I approached, one of the men gestured towards my boat, her freshly painted wood and fine lines too pretty by far amid the ruined lobster traps, discarded lines, and sun-bleached husks of fish on the beach.

You like the ocean? he asked in English. Not waiting for a reply, he held up his hands as if to ward off the sea and said, I dont.

The other fishermen glanced at my boat as they worked, pulling at their grimy nets and tossing out small crabs and strands of seaweed. Big surf rumbled shoreward in broad swaths of foam.

We go out because we have to to live, the man continued.

I nodded. But the ocean is very beautiful here, I said.

Not beautiful, he said. Peligroso.

Peligroso tambin I agreed.

He asked what I did for work as he wrenched a foot-long sand shark from his net with a popping sound, then pitched it to the sand.

Im a writer, un escritor, for a surfing magazine, I told him.

You better write a lot, he said, gesturing at the surf, if youre going out there.

I built Cormorant, my 18-foot open boat, in 22 months from August 2005 to June 2007 on weekends and nights in the single-car garage of the studio apartment I rented in San Clemente, California. Working from a set of plans drawn by Iain Oughtred on the Isle of Skye in Scotland, I laminated stem and stern pieces; set up molds for the hull on a building frame; cut, bent, and secured planks; and saw a vessel steadily emerge from my efforts.

Pointed at both ends, with sleek, even curves, Cormorant carries more than a hint of her Viking longboat lineage. Under sail she glides through the water, with a large, trapezoidal lugsail for the main and a smaller, triangular mizzen sail, both in tanbark, which glows red in afternoon light.

I also had a set of narrow-bladed oars meant for sea work, and two spare oars as well. There would be no motor.

Modeled on traditional Shetland Islands fishing craft called sixareens rugged, open boats that plied the North Atlantic from the Viking age until the advent of internal combustion Cormorant differed from them only in her modern materials: Marine-grade plywood for the hull, secured with epoxy to timbers of Douglas fir for the keel.

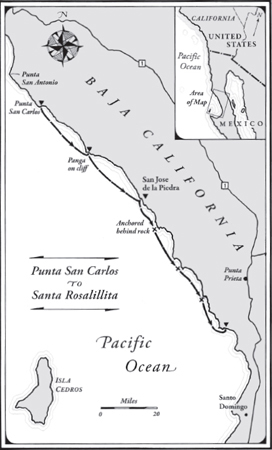

A two-week supply of food, water, and gear in dry bags fit neatly in the boat, and I secured my surfboard in a padded bag over the top of my stowed equipment. My plan was to sail the sparsely populated Pacific coast of central Baja, landing in coves to camp and ride waves. This was a test run, a short getaway from work to gauge the feasibility of longer trips in the future. For now, I budgeted 10 days to sail along 100 miles of coast.

A culmination of various impulses for time alone, for wilderness surfing, and for something I thought of as full nature immersion the expedition before me also represented a living experiment. I had the notion that traveling in an ancient mode, removed from the ceaseless roar and electronic thrum of contemporary life, I could connect to the most basic aspect of my nature. Not so much my nature as an individual, but my nature as a member of our species shaped by longstanding, elemental human practices and by the elements themselves.

I wanted to know more about what I had come to think of as blood memory a physical intimation I had of my ancestors knowledge. I felt it once, clearing brush under a low forest canopy in the Santa Cruz Mountains. It had come to me unmistakably, in the hard physical labor, that my body had been formed by the very work that I was engaged with: cutting limbs with a handsaw and hauling them down the steep hillside. Even the slant of the light through the trees all of it was already in me and was merely activated by repeating what my ancestors had done.

Cormorant was my way of trying to know the world as it was before a wilder place, where magic showed itself in weather and animal encounters.

Big waves, cresting far outside the point, with 10-foot walls of foam crashing in, prevented me from launching Cormorant on the morning I first met the fishermen. I surveyed the next point south through my binoculars and saw massive plumes of whitewater and muscular bands of swell stretching out to the horizon. Picturing Cormorant smashed to pieces in the shorebreak, I decided to wait, make coffee on the camp stove, and organize my gear. Later, I drove into the deserted fish camp, the plywood shacks leaning slapdash and empty like so many forts built by slingshot-toting boys. The place was empty, without even a skinny dog around to bark a warning.

Leaving my wagon and boat, I walked into the desert and climbed the first knoll about three-quarters of a mile back on the coastal plane. Brick-red pumice stones covered the ground, and little sage plants and delicate desert flowers splashed the hillside.

I made a sketch of the camp and the headland some miles south and Punta San Carlos to the north, with the broad sweep of the bay, and including the huge mesa between the two that tops a long run of steep ravines. Below my hillside perch, the 15 shanties of camp seemed the perfect representation of mans world ordered even in their loose conglomeration but paltry in design compared to these intricate and aromatic plants.

I was born in 1969, and I grew up in Newport Beach, California. I lived with my mother during the week and with my dad on the weekends, sleeping on a yellow vinyl pad on the floor of the room he rented from an elderly lady. In the morning, at first light, we surreptitiously put the pad back on her patio furniture, and set off for the beach.

Dad took me to surf spots all around Southern California from the time I was little, and I rode a foam surfboard he bought me, wearing a thick wetsuit with short legs and long sleeves. I loved the petroleum smell of neoprene and the pervasive smell of surf wax in the shops we visited in my yearning for a fiberglass board.

Dad would not let me get one at first, because hed almost drowned in the 50s at Malibu when the surfer-actor, Peter Lawford, ran into him on a redwood plank and knocked Dad cold. He would have preferred if I just bodysurfed like him, particularly since he didnt like the pot-smoking surf culture of the late 1970s, being more of a Tony Bennett and Frank Sinatra man.

We stopped at liquor stores after the beach, where Dad would get a Coors in a paper sack for the road and buy me Twinkies and chocolate milk. Lets not tell your mother about this, he said every time.