The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

This book is dedicated to my UNICEF colleagues on the ground and around the globe, who put their lives at risk on behalf of children, every day.

AUTHORS NOTE

This book was written as a personal story. It is based upon my own experiences, my memory of those experiences, and the perceptions I have formed as a result. It is not to be construed as a UNICEF publication or a U.S. Fund for UNICEF publication. I have chosen to direct 100 percent of royalties I would otherwise receive to the U.S. Fund for UNICEF to benefit vulnerable children around the world. For more information, please visit unicefusa.org/bookroyalties.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

If it takes a village to raise a child, it takes a universe to write about it. Thank you to Seth Schulman, who helped me to find the right words to tell my stories and whose editing of my writing helped them to come alive. Thank you to my agent, Lorin Rees, for believing in the project, and to George Witte and all the folks at St. Martins Press for sharing that belief. I am forever indebted to my dear friends and colleagues Brian Meyers, Emily Distel, Lisa Szarkowski, and Harry Wall. Their research, their additions, their willingness to read every word again and again (as well as the fact that they kept me laughing throughout the year of writing) were invaluable. Finally, thank you to the people who make me who I am: to my mom and dad, Manny and Edwin Stern, as well as to my brother, Mitchell Stern, who made our home a place where we learned to care about the world around us. To my husband, Donald, who not only kept the light on at home as I ran around the world, but whose arms welcomed me back each time. To my sons, Brian, Lee, and James, who accepted that work often kept me from being home at the end of the day, and to my friend Naomi, who listens to it all and helps me balance it. All of you have made possible the journey that has now become this book. I love you all.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

by Ta Leoni

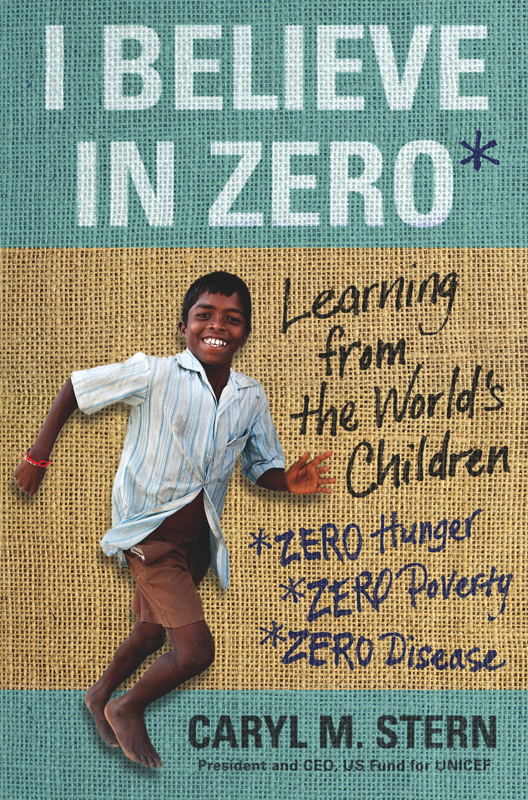

ACTRESS TA LEONI is a third-generation member of the UNICEF family. Her grandmother Helenka Pantaleoni cofounded the U.S. Fund for UNICEF in 1947 and served as its president for twenty-five years. Anthony Pantaleoni, Tas father, is an active member of the U.S. Fund for UNICEFs board of directors, serving as board chair from 2008 to 2012.

Though Ta has been a UNICEF volunteer since childhood, her formal service began in 2001, when she was named UNICEF ambassador. In 2006 she was elected to the U.S. Fund for UNICEF national board. She continues in both roles and has been a tireless fund-raiser and advocate for the worlds children in support of UNICEFs mission.

Heroes wear capes.

Capes are for those who dare to leap from tall buildings or pull stranded cats out of towering trees. The ones who always land on their never-tired feet, and whose story always ends with white teeth gleaming in a glory shot.

But there is no cape here, not for this author.

Because Caryl Stern didnt write this book as a hero, she wrote it as a mother. And like every mother in the world, she loves her children above all else. She would carry them down a mountain for air, she would find them in the middle of the farthest desert, and she would make the first flight back from anywhere to be with them when they needed her. Youll read more about that later.

Caryl came to the U.S. Fund for UNICEF for another job and became the president of the organization six months later. She came as an accomplished defender of human rights and quickly proved to be an outspoken and outstanding advocate for children. She also came without any field experience and a very pronounced, irrational fear of bugs (the latter of which has entertained every one of us who has ever had the chance to travel with her).

But it is Caryls strength as a mother that guides her eyes and ears and heart in these pages.

She writes about what it is to face another mothers loss or a childs pain when there is no chance to turn away or turn it off, and of the awesome and constant strength of the human spirit that she has witnessed in conditions most of us could never even imagine. She writes about the day she saw a mother in the middle of the desert and they shared an apple from New York, and the day she stood by and held the hand of a new mother as her baby took its last breath.

She doesnt write as some kind of fearless hero with all the answers, leaving pages full of solutions and cures in her wake. She tells these stories with a kind of honest humility that is rare.

She admits to missing the hot showers of home, to feeling ashamed of not doing enough, to being afraidwhether for her own life amid the aftershocks in Haiti, or just of something crawling into her tent. And she writes of wanting to get home to her children, like every mother in the world.

There isnt a need to exaggerate the plight of millions of women and children around the world, but there is always the need for an honest and powerful witness.

Caryl is that witness, because she isnt just reporting what she sees, she is telling us what is there.

On one of her earliest trips, to Sudan, Caryl made a promise to those she met in one of the camps, that she would use her voice to tell their stories and to get others to listen. These are their stories.

After reading this book, I realized that perhaps more than anything else, Caryl has written about why we must believe in zero.

Because these are not their children, they are all our children, each and every one. As for the cape? I may know better, but I bet there are children out there in the world that would love to peek into Caryls duffel bag to see where she keeps hers.

1. ROSAS WALK

Mozambique, January 2007

REGARDLESS OF WHERE I HAVE TRAVELED, to a major city in an industrialized country or a small remote village in a developing nation, I have found three things to be true.

First, where I see children, there will be some sort of ball. Sometimes the ball is made of rubber or plastic, often just rags held together by twine, but always I see a child tossing it or kicking it and at least one other child returning it in much the same fashion.

Second, my lap is not my personal property. If I plop down on the ground and sit patiently, a child will eventually find his or her way onto my lap.

Third, and most important, parents everywhere want the same things for their children. We want them to be healthy. To be safe. To feel loved. To have an education. To dream big dreams and have a fighting chance to realize those dreams. This is the same everywhere in the world, no matter how much people have to eat, how accessible education may be, or whether the community has running water, electricity, or basic health care. We each define success differently, but as parents, we all want the best for our children.

It was in Mozambique, at a birthing clinic, that I first met Rosa. The site was accessible only by a rutted dirt road, so far from stoplights or street signs or any other markers that I marveled the driver of our jeep had even found it. The clinic was a primitive structure composed of two rooms, a birthing room and a maternity ward. It did have walls, windows, electricity, and running waterfour things I had rarely seen as we had driven through the countryside. Still, no air-conditioning or ceiling fan, only the relief that comes from being inside and thus shaded from direct sunlight. It was hot, stifling, hard to breathe.