Sommaire

Pagination de l'dition papier

Guide

InterVarsity Press

P.O. Box 1400, Downers Grove, IL 60515-1426

Internet: www.ivpress.com

E-mail:

Introduction and chapters one, two, three, five, nine and eleven 1998 by InterVarsity Christian Fellowship/USA. Chapter four 1998 by Susan Cho Van Riesen. Chapters six and eight 1998 by Peter Cha and Susan Cho Van Riesen. Chapter seven 1998 by Peter Cha and InterVarsity Christian Fellowship/USA. Chapter ten 1998 by Peter Cha.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from InterVarsity Press.

InterVarsity Press is the book-publishing division of InterVarsity Christian Fellowship/USA, a movement of students and faculty active on campus at hundreds of universities, colleges and schools of nursing in the United States of America, and a member movement of the International Fellowship of Evangelical Students. For information about local and regional activities, write Public Relations Dept., InterVarsity Christian Fellowship/ USA, 6400 Schroeder Rd., P.O. Box 7895, Madison, WI 53707-7895, or visit the IVCF website at .

Scripture quotations, unless otherwise noted, are from the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

ISBN 978-0-8308-7524-5 (digital)

ISBN 978-0-8308-1358-2 (print)

This digital document has been produced by Nord Compo.

To our parents

Introduction: Learning Our Names

Paul Tokunaga

ON THAT 1-10 SCALE MANY OF US LIVE BY, WHITE FOLK WERE always a 10. I was convinced, as an Asian American, that the highest I could ever hit was a 7. I grew up in a predominantly white suburb in the San Francisco Bay area. It was clear to me, even as a child, that whites set the standards and I had to fit into their society if I was going to prosper, or even just survive.

In third grade at Hamilton Elementary, two large fifth-grade boys took me aside. OK, kid, open your eyes as wide as you can. Yessir, two large fifth-grade boys, can do, I thought. I practiced all the time at home in front of a mirror. All the Japanee, Chinee, slant-eye jabs from my classmates told me round eyes were much better than my more angular model. With all the elasticity my eye muscles could muster, I made like an owl, which sent my fifth-grade antagonists rolling in their racist laughter.

When we took the standardized tests in sixth grade to determine how we measured up to the rest of the country, I penciled in my name: Paul Michael Tokunaga. I proudly admired it. When my mother later saw it, she did not. She sat me down to write five hundred times: My name is Paul Minoru Tokunaga. I was doing all I could to blend in. I was embarrassed by my Japanese heritage. I wanted to be as white aS I could. White was right. Japanese was not.

The physical comparisons wouldnt let up. No matter how much I yanked on my nose and pinched my wide nostrils, they still wouldnt look like Joe Montanas or Clint Eastwoods. My jet-black hair would not curl unless I slept on it the wrong way, and none of my stretching exercises made me into a six-footer. Of course, the worst came in the high-school locker rooms: why, why, why couldnt I grow hair on my chest like my Italian friends?

Going away to college and having friends who werent so hung up on appearance, I was able to relax some. But it was clear: if I could choose, Id pick being white over Japanese any day. Any day.

It took an earth-shaking breakup with a Caucasian woman in college for racial reasons (her mom: What will the neighbors say? What will your children look like?) to make me face reality: Paul, you aint white, you aint never gonna be white in fact, why do you even wanna be white? That Damascus Road-like experience forced me to stare at the mirror to see my face and my heritage. God did make me Japanese. Did he goof? Was it a celestial computer error? Was I supposed to be Paul Michael or Paul Minoru?

How Could I Affirm Both as One Person in One Body?

It has not been a smooth road of self-discovery. I have Japanese days and I have American days. Some days I think my Japanese values are the best and American qualities stink to high heaven. Then, when I hear of an Asian American student who is totally stymied by her parents adamant goals for her life (Christine, you must be doctor! Must!), I ache and get angry at the level of control in many Asian American parents. I am very grateful for the freedom to choose our own road that my parents somehow were able to give us children.

At some point in my early twenties, Mom and I were sitting around the kitchen table, working on our fourth cup of coffee, catching up with each other. For some reason, Im proud to be Japanese came out of my mouth.

What? was Moms dumbfounded response. I thought you were ashamed to be Japanese.

I had to admit that for years I had been, but in recent years I had begun to own my Japaneseness and it was growing on me. Later that night, I reflected, Maybe, just maybe, I can be a 10.

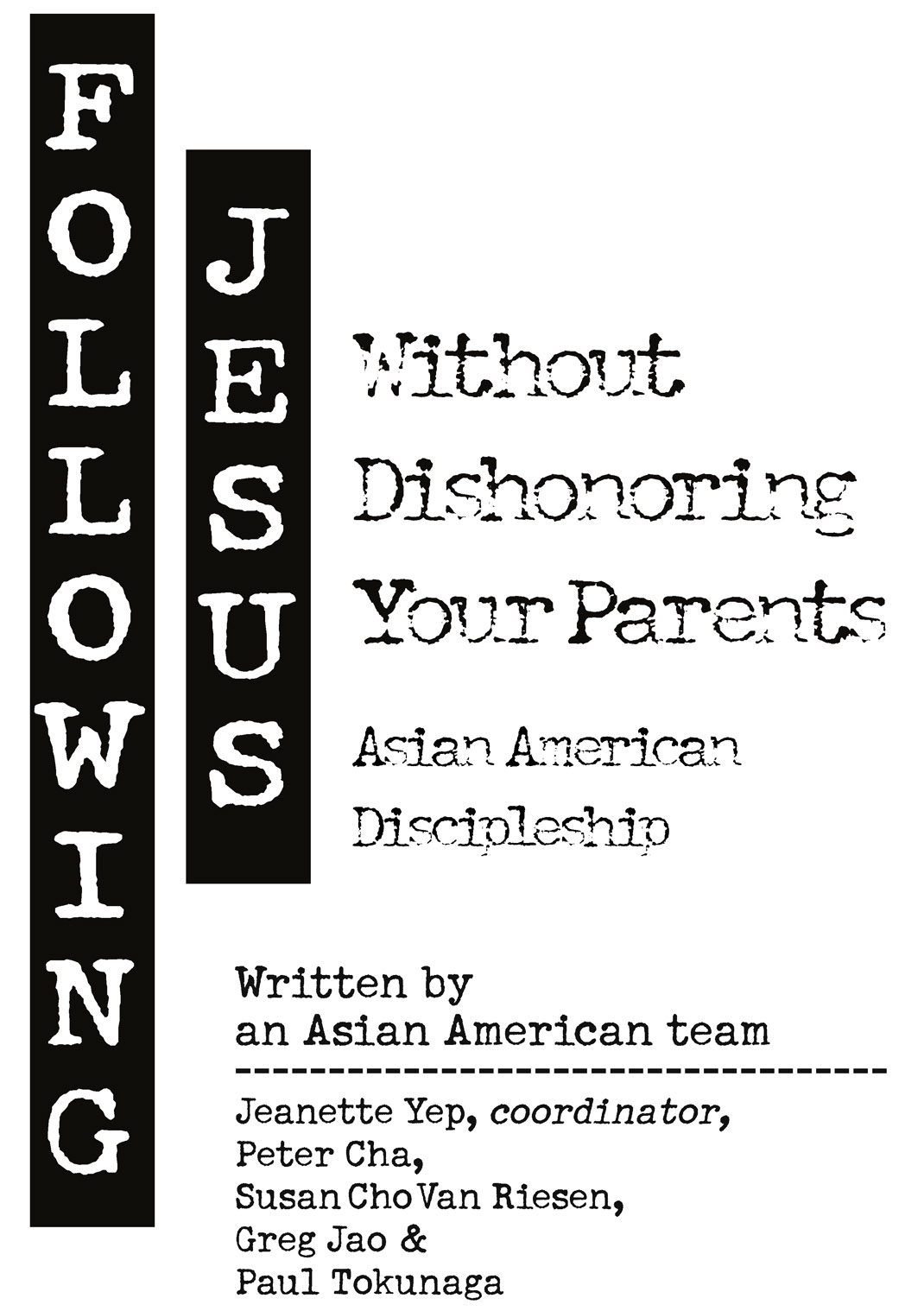

The Fight for Asian Americans

A couple of decades ago, John White wrote a wonderful book on Christian discipleship called The Fight. As our writing team wrestled with the thrust of the present book, we sensed a need for a sort of The Fight for young Asian Americans. DiscipleshipAsian American stylewas what we wanted to address.

In this book we seek to address a large question: How can I, as an Asian American (primarily college age to thirtyish), follow Jesus with all my heart, mind, soul and strength? The natural follow-up questions are What unique qualities about us enhance our ability to love Jesus? and What unique qualities or circumstances keep getting in the way of fully giving our lives to him?

Our aim is to speak to Asian Americans who are somewhere on the journey of discovering they are both Asian and American. Being both means always living with a built-in tension. Those of us who experience less tension than others may celebrate their ethnic heritage. Thats great! We hope that reading this book will help you grow in your depth of understanding and obedience. If you are not Asian American, we warmly invite you into this book as a way to get to know us better.

Each chapter addresses what we feel are the major issues we face as Asian American Christians. In each chapter we seek to bring in the insight and authority of Gods Word to shed light and bring wisdom from on high.

An interesting phenomenon occurred as we began writing and then reading each others chapters: our parents kept emerging everywhere! Although we devote two chapters exclusively to relating to our parents, their influence showed up in almost every other issue we addressed. Thats because they are so important and integral to who we are. On the one hand, we have tried to honor them. On the other hand, we also want to be truthful about some of the pain we feel from being our parents children (recognizing, as well, that we have often caused them great pain). We prayerfully hope we have been both loving and honest.

Our book has several shortcomings, and we want our readers to be aware of what they are. We struggled with each of these because we knew they were important and deserved addressing, but space limitations forced us to narrow our focus. We offer our apologies for these shortcomings.