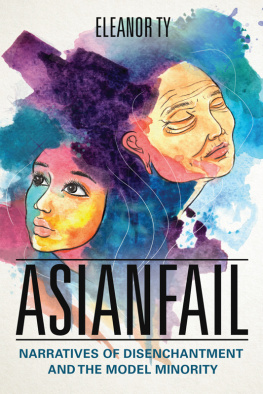

Asianfail

THE ASIAN AMERICAN EXPERIENCE

Series Editors

Eiichiro Azuma

Jigna Desai

Martin F. Manalansan IV

Lisa Sun-Hee Park

David K. Yoo

Roger Daniels, Founding Series Editor

A list of books in the series appears at the end of this book.

Asianfail

Narratives of Disenchantment

and the Model Minority

ELEANOR TY

The University of Illinois Press gratefully acknowledges

financial assistance provided by Wilfrid Laurier

University Office of Research Services for the

publication of this book.

2017 by the Board of Trustees

of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

1 2 3 4 5 C P 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016958953

ISBN 978-0-252-04088-7 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-0-252-08235-1 (paperback)

ISBN 978-0-252-09938-0 (e-book)

Contents

Illustrations

FIGURES

TABLE

Acknowledgments

I thank my colleagues and students in the Department of English and Film Studies at Wilfrid Laurier University for their friendship and for providing a stimulating teaching and working environment. Thanks are due to the Research Office and the Vice-President: Academic for encouraging my project with course releases and with the University Research Professor award in 2015. The project was initially funded by a grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

For lively and thought-provoking conversations about reading and teaching Asian North American and graphic narratives, I am grateful to Monica Chiu, Patricia Chu, Roco Davis, Don Goellnicht, Y-Dang Troeung, Julie Rak, Thy Phu, and members of the Toronto Pacific Exchange reading group. It was a pleasure to work with intelligent and efficient editors at the University of Illinois Press, especially Dawn Durante and Jennifer L. Comeau. And thank you to my family members, David, Jason and his wife Clare, Jeremy, and Miranda Hunter, for their continuing love and patience.

were originally published as Little Daily Miracles: Global Desires, Haunted Memories, and Modern Technologies in Madeleine Thiens Certainty in Moving Migration: Narrative Transformations in Asian American Literature , edited by Johanna C. Kardux and Doris Einsiedel (Berlin: LIT Verlag, 2010), 4560.

Parts of were originally published as Affect, Family, and the Past in Two Plays by Catherine Hernandez in Asian Canadian Theatre , edited by Nina Lee Aquino and Ric Knowles (Toronto: Playwrights Canada Press, 2011), 21222.

Asianfail

Introduction

The hashtags #Asian Fail, #failasian, and #Asianfailure on Tumblr, Instagram, and Twitter feature tweets, pictures, and anecdotes of Asians who fail at doing what Asians are supposed to be good at. Asians make insider jokes about their own inability to pick up food with chopsticks, to cook rice, or to shine at math and computers. Many of these posts are funny, riffing on cultural stereotypes of Asians who are supposed to excel at playing the violin or who are so nerdy that they have no social or sex life. Some examples:

FailAsian, July 7, 2011: I only got an A instead of an A+

@Asian_Failure, September 2, 2011: 30% of Chinese adults live with their parents

FIGURE 1. High-expectation Asian father on Spelling B meme

FIGURE 2. #Asianfail examples from Twitter, February 2015

Jenny C.: being destroyed in badminton failAsian

July 22, 2011, High Expectations Asian Father: You got B+ on blood test? Failure runs through veins.

The U.S. Context: Model Minority Discourse

The more serious side of this phenomenon of high expectations of Asian subjects in North America has been referred to as the problem of the model minority, especially in the United States. Since the 1960s, Asian Americans have been used as examples in contrast to other minority groups, such as blacks and later Latinos, who were perceived to be less successful in schools and in their professions (see Osajima 215ff.). An oft-cited 1966 article in U.S. News and World Report praised Asian Americans for discipline, low crime rates, a willingness to work hard, and strong family values. Besides presenting the questionable view of America as the land of opportunity for individuals who worked hard (Osajima 217), the article reinforced stereotypes about Asians and the myth of the model minority, entrenching some problematic assumptions that would last for the next couple of decades. As Keith Osajima explains, Asian American success constituted a direct critique of Blacks who sought relief through federally supported social programs. The achievements of Asians diffused the black militants claim that America was fundamentally a racist society, structured to keep minorities in a subordinate position. The Asian American experience identified cultural values and hard work as the keys to success(217). One critical issue was the blunt use of race, which, as Tomo Hattori notes, functions as the general equivalent, as the standard measure that makes human bodies and racial culture commensurable and equal to each other, resulting in a flattening of human diversity into racial fact (230). Sze Wei Ang also notes the paradoxical use of race: the myth of the model minority allows critics to dismiss the fact that race plays a part in socio-economic processes, but even then, the myth continues to depend upon race for its very construction. Historical materialist critiques of this myth furthermore identify it as a function of capitalist ideology that tries to protect private property rights at the expense of state policies, such as affirmative action (12122).

Scholars have questioned the kind of success model minority discourse lauds, as it is seen as the (re)production of representations of the successful formation of a particularly constructed Asian American subjectivity (Palumbo-Liu, Asian/American 396). Remarking on the popularity of novels such as The Woman Warrior , The Joy Luck Club , Typical American , and China Boy in the 1990s, David Palumbo-Liu argues that in model minority discourse we find the instantiation of a collective psychic identification that constructs a very specific concept of the negotiations between social trauma and private health ( Asian/American 398). Happiness is promised to those who subscribe to hegemonic ideologies (398) that promote the work ethic of self-affirmative action or the attainment of upward mobility on the strength of inner conviction and self-help (399). Like self-affirmative action, model minority discourse assumes that individuals can transcend specific historical and material conditions in order to achieve happiness. The need for structural change, for governmental support of programs that enable minority groups to gain equal access to privileges usually accorded to dominant groups, is thus elided. Palumbo-Liu notes that popular Asian American narratives animate the expected themes of subject-split, cultural alienation and confusion, and coming-to-terms that fits the stereotypical image of the model minority (410). This type of literature of an assimilated group now at peace after a phase of adjustment is dangerous in its powerful closing-off of a multiplicity of real, lived, social contradictions and complexities that stand outside (or at least significantly complicate) the formula of the highly individuated identity crisis (410). Similarly, Victor Bascara criticizes model minority discourse and argues that critique of the model minority stereotype can be understood as a critique of U.S. imperialism: The model-minority myth has functioned as a way of reading progressive historical change. That is, the present has reckoned with uncomfortable pasts and is doing right by the wronged by incorporating them, or more precisely, by allowing a putatively color-blind and gender-neutral market to sort things out. The resulting vision is the smooth and compliant incorporation of Asian difference into American civilization (2).

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.