Buffalo Bird Womans Garden

Buffalo Bird Woman, 1910 (photographed by Gilbert Wilson; Minnesota Historical Society 9771-A)

Buffalo Bird Womans Garden

Agriculture of the Hidatsa Indians

GILBERT L. WILSON

With a new introduction by

Jeffery R. Hanson

MINNESOTA HISTORICAL SOCIETY PRESS

ST. PAUL

Borealis Books are high-quality paperback reprints of books chosen by the Minnesota Historical Society Press for their importance as enduring historical sources and their valuable accounts of life in the Upper Midwest.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

Minnesota Historical Society Press, St. Paul

www.mnhs.org/mhspress

Originally published as Agriculture of the Hidatsa Indians: An Indian Interpretation,

copyright 1917 by the University of Minnesota

New material copyright 1987 by the Minnesota Historical Society

International Standard Book Number 0-87351-219-7

E-book ISBN: 978-0-87351-660-0

10 9 8 7 6

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wilson, Gilbert Livingstone, 18681930

Buffalo Bird Womans garden.

Reprint. Originally published: Agriculture of the Hidatsa Indians.

Minneapolis. 1917.

1. Hidatsa IndiansAgriculture.

2. Indians of North AmericaGreat PlainsAgriculture.

3. Waheenee, 1839? .

4. Goodbird, Edward.

I. Title.

E99.H6W74 1987 630.978 8720355

ISBN 0-87351-219-7

CONTENTS

PHOTOGRAPHS

INTRODUCTION

Buffalo Bird Woman, known in Hidatsa as Maxidiwiac, was born about 1839 in an earth lodge along the Knife River in present-day North Dakota. In 1845 her people moved upstream and built Like-a-fishhook village, which they shared with the Mandan and Arikara. There Buffalo Bird Woman grew up to become an expert gardener of the Hidatsa tribe. Using agricultural practices centuries old, she and the women of her family grew corn, beans, squash, and sunflowers in the fertile bottomlands of the Missouri River. In the mid-1880s, U.S. government policies forced the break up of Like-a-fishhook village and the dispersal of Indian families onto individual allotments on the Fort Berthold Reservation, but Hidatsa women continued to grow the vegetables that have provided Midwestern farmers some of their most important crops.

In Buffalo Bird Womans Garden, first published in 1917 as Agriculture of the Hidatsa Indians: An Indian Interpretation, anthropologist Gilbert L. Wilson transcribed in meticulous detail the knowledge given by this consummate gardener. Following an annual round, Buffalo Bird Woman describes field care and preparation, planting, harvesting, processing, and storing of vegetables. In addition, she provides recipes for cooking traditional Hidatsa dishes and recounts songs and ceremonies that were essential to a good harvest. Her first-person narrative provides todays gardener with a guide to an agricultural method free from fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides.

For many white Americans and Europeans, the very idea of farmer-Indians on the Great Plains is unfamiliar. Most people think of Plains Indians as the nomadic tribes who, mounted on horseback and free from agrarian ties to the soil, roamed the Plains in search of the buffalo. Hunters and warriors, provident with nature and fiercely resistant to subjugation, tribes like the Dakota, Comanche, Cheyenne, and Blackfeet have come to typify Plains Indian life. In dime novels, fiction, movies, and history books, these Plains Indians have symbolized not only the drama and romanticism of the Old West, but a disappearing lifeway as well. The nomadic Plains tribes became, in the American mind, the quintessential Indians: standard-bearers of a bygone age, remembered for their noble qualities of courage, freedom, and a oneness with nature.

The other kind of Plains Indian is one to whom popular sentiment and to a lesser extent historians have paid far too little attention. These are the Village Indians of the Great Plains, sedentary farming peoples whose ancient lifeways and contributions to history and civilization have gone largely unsung. In the Northern Plains, the Hidatsa, Mandan, and Arikara (known now as the Three Affiliated Tribes) were once numerous, powerful, and independent tribes controlling practically the entire Missouri River Valley in what is now North and South Dakota. Their cultural adaptations represent a much more ancient and indigenous Plains Indian tradition than the typical cultures of the nomadic Plains tribes, which depended on horses introduced by Euro-Americans.

The Hidatsa inherited a cultural legacy that had long withstood the test of time. Archaeologists have named their lifeway the Plains Village Tradition and traced it back to A.D. 1100 in the Knife River-Heart River region of the Missouri Valley, the historic homeland of the Hidatsa and Mandan.

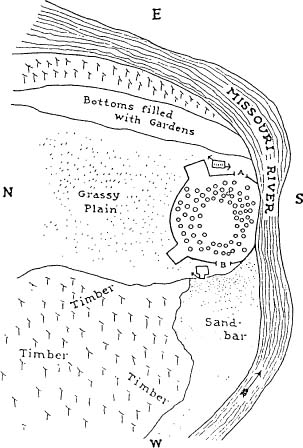

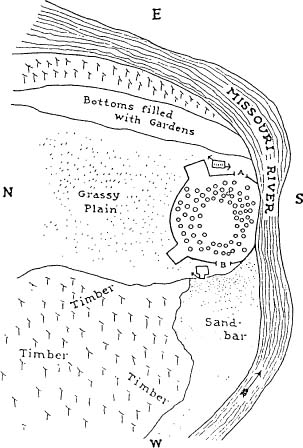

Agriculture provided the distinctive flavor of this lifeway. The commitment to permanent villages, the unique and complex architectural achievements shown in the earthlodges, the settlements and community plans of villages (see Figure A), and the ceramic traditions, all testify to an agricultural legacy that lasted over seven centuries in the Northern Plains. This legacy is imbedded not only in the soil but also in the lives, minds, and hearts of those who inherited it, nourished it, and preserved it. It is to these people, the Hidatsa, Mandan, and Arikara, that historians and anthropologists have turned for this knowledge.

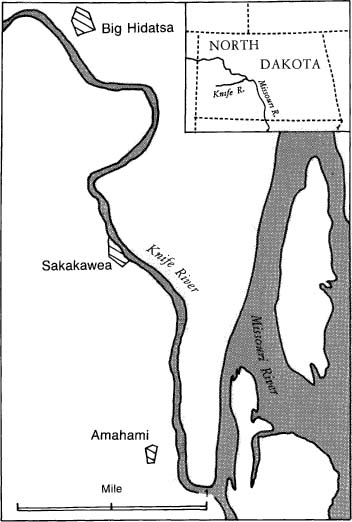

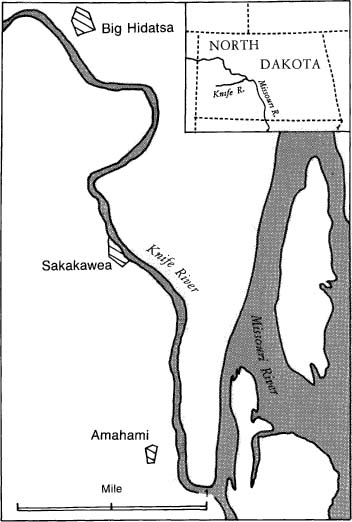

Before the 1830s, members of a large and powerful Hidatsa tribe farmed, hunted, and traded from their traditional villages near the mouth of the Knife River. The Hidatsa were divided into three closely related subgroups who, from about 1787 until 183445, maintained distinct and independent villages: the Hidatsa-proper, who inhabited Big Hidatsa village on the north bank of the Knife River (see Figure B); the Awatixa, who lived about a mile downstream from the Hidatsa-proper in Sakakawea village; and the Awaxawi, who lived in Amahami village about one mile south of Sakakawea at the mouth of the Knife River.

Figure A. The site of Like-a-fishhook village (Old Fort Berthold), which followed a typical Plains village settlement pattern (drawn by Frederick Wilson and published in The Hidatsa Earthlodge, Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History 33[1934]: 341)

These subgroups had much in common. They shared a language, a family organization in the form of matrilineal clans (where descent, property, and subgroup identity was traced through the mothers family), fraternal and sororal organizations graded by age, and a cultural commitment to agriculture. The subgroups, however, had different origin stories, dialects, and ceremonial patterns, and it has been said that they had no collective name for all three village groups before the arrival of the whites.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.