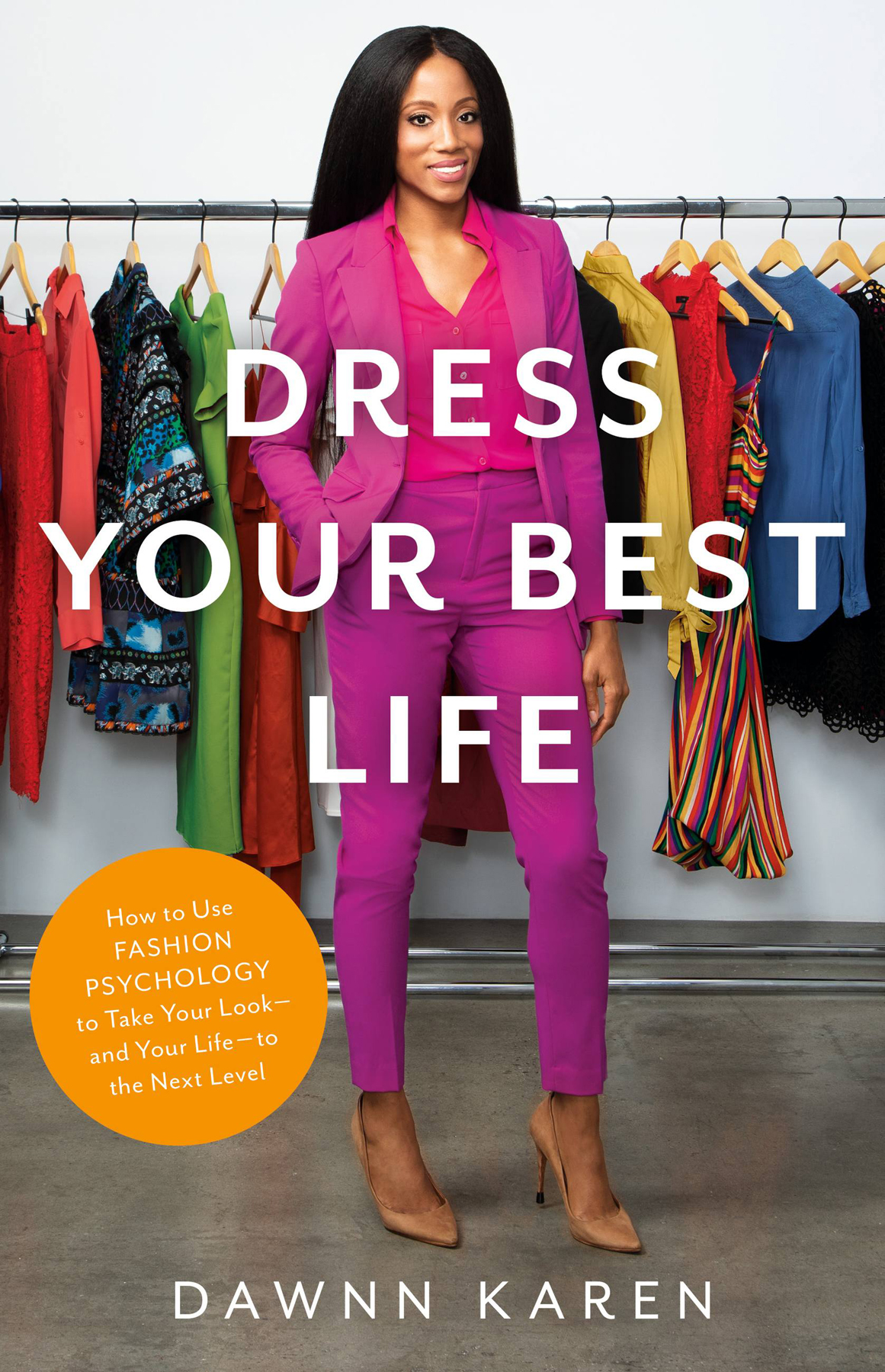

Copyright 2020 by Dawnn Karen Mahulawde

Cover design by Lauren Harms

Cover photograph by Heidi Gutman

Cover 2020 Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Little, Brown Spark

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

littlebrownspark.com

twitter.com/lbsparkbooks

facebook.com/littlebrownspark

First ebook edition: April 2020

Little, Brown Spark is an imprint of Little, Brown and Company, a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown Spark name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

ISBN 978-0-316-53098-9

E3-20200229-JV-NF-ORI

To Rosa-Lee Baby Cooper Cooper

We delight in the beauty of the butterfly, but rarely admit the changes it has gone through to achieve that beauty.

Maya Angelou

W hat if I told you fashion was a readily available, solidly reliable way to feel more in control of your life? That there are ways to match your clothing to your mood, to use accessories to conjure comfort, to reduce anxiety through color and fabric choices, to project power when you need it most? Clothes can help us maintain our cultural identity even when our environment demands we assimilate. Conversely, they can help us fit in when doing so is advantageous. With everything Ive discovered about Fashion Psychology, I cant wait to help you break out of style ruts, create uniforms when useful, prevent the dreaded I have nothing to wear feeling, curb compulsive shopping behaviors, and avoid trends when they wont work for your lifestyle or your budget. What if I told you clothes can help you lift yourself up out of despair? Fashion is not meaningless. Far from it. Fashion is the voice we use to declare ourselves to the world.

The first time it occurred to me to practice psychology within the framework of fashion, I was twenty-one, working toward dual masters degrees (a Master of Arts and a Master of Education) in the Counseling Psychology Department at Columbia Universitys Teachers College. As a recently graduated psychology major from Bowling Green State University in Ohio, I had spent my entire life in the Midwest. But when I arrived in New York for grad school, I hit the ground running. In addition to taking classes, I quickly achieved some side-hustle success as a runway model and fashion PR assistant. Though I served up fierce lewks on the runway, the truth is Im an introvert and a keen observer of those around me. I was awed by the kaleidoscope of styles I encountered on the subways and streets of my new city. As I clocked the outfits of my fellow students, other models backstage, and everyday New Yorkers, I just couldnt get this question out of my head: What do your clothes reveal about your psyche? This idea was the seed from which Fashion Psychology (as I came to call it) would grow. I knew back then by instinct what I know now from academic research and clinical experience: People express their emotions, their well-being, even their trauma through their clothes. And clothes, in turn, can be a powerful tool for healing. I know this because Ive lived it.

From the moment I set foot in Manhattan, I was home. The rhythm of the city just felt right. I was already accustomed to a rise-and-grind lifestyle, ready to balance rigorous academic demands with my creative passions. Growing up, I was a singer, studying opera and musical theater at the Cleveland School of the Arts. I had always excelled in my classeseven skipping the fifth gradethanks to my curious mind and unending desire to please my parents. Achievement meant a lot in my family, especially to my father, a Jamaican immigrant who worked as a middle school janitor. My mom was an administrative assistant in a hospital, raising my brothers and me largely on her own, because my parents were never married. My twin brother and I shuffled back and forth between our parents homesthe weekdays at our moms and the weekend at our dads. (My baby brother has a different father, whom he visited separately.) Studying hard and being onstage gave me an identitythe performer and the risk takerthat helped me distinguish myself from my shyer, more reserved siblings.

But life in the spotlight definitely created some tension between my peers and me. In middle school I was bullied for my appearance (I was tall and thin with glasses) by a guy who, fifteen years later, asked me out on Facebook. One girl in particular (a best friend who was anything butknow the type?) loved to talk about her designer clothes and would ask me pointedly about mine. I owned none. My father felt fancy labels were wasteful since, he reasoned, you could buy the same quality itemminus the brand namefor a fraction of the cost. In high school I was targeted for having an operatic voice and not a church voice. In college a sorority sister relentlessly made fun of me for deciding to shave my head and later, in colder weather, for experimenting with head scarves similar to the hijabs worn by Muslim women. Insecure as all of this made me, I always felt a deep urge to challenge norms with my look. Being creative with my style, utilizing whatever I had in my closet, was a major source of joy for me. It still is. Good grades and cheering audiences were external affirmations that I belonged where I was, and that I wasnt as out of place as my bullies would have me believe.

So when I started grad school at Columbia, I followed my trusty formula. I studied hard, worked hard, and said yes to every modeling gig that came my way. In my downtime, I designed and hand-made dramatic pearl and feather jewelry and christened my line Optukal Illusion (#truth). I made some fierce new friends, and they modeled my creations for promotional photos. I also volunteered at the Barnard/Columbia Rape Crisis Anti-Violence Support Center. It was work that felt like a calling, and it would become meaningful in a way I could not have foreseen. I was what my professors might call an ambitious self-starter. Being one of only a handful of black students in my program and from a lower-middle-class background, I felt I had everything to prove.

I was motivated, focused, and firing on all cylinders. I enthusiastically approached several professors for guidance, pitching this idea I had to practice Fashion Psychology, hoping they could help me find a job. But the field, as far as I could tell at the time, didnt seem to exist. One professor acknowledged that my rsum seemed to be a fifty-fifty split, with half my experience rooted in the world of fashion and the other half in the world of Freud. She urged me to seek an entry-level position assisting a renowned celebrity stylist. The stylist, however, had an infamous reputation for tearing down clients before building them back up with a makeover. Her approach just didnt sit right with me. Nor did it seem forward-thinking, given the messages of self-acceptance, body positivity, and inclusivity that were beginning to bubble up in pop culture, though they hadnt yet reached critical mass in the fashion industry at the time.