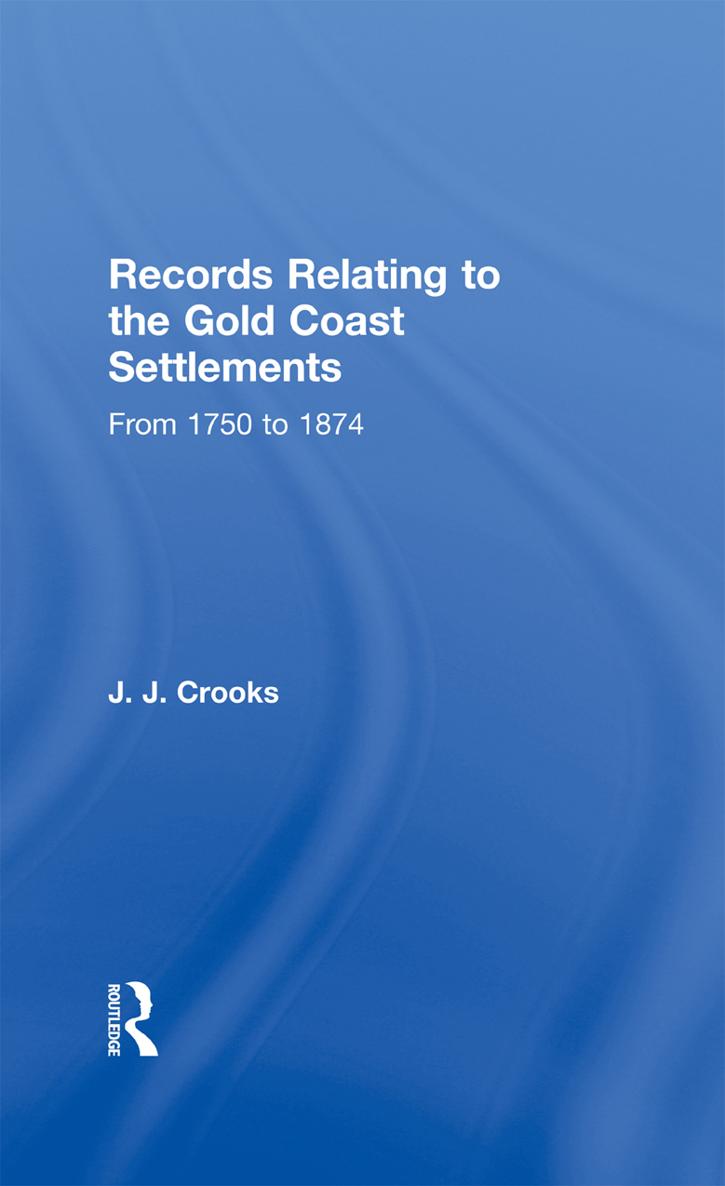

First published 1973 by

FRANK CASS AND COMPANY LIMITED

This edition published 2012 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

First edition 1923

New impression 1973

ISBN 0 7146 1647 8

RECORDS

RELATING TO THE

Gold Coast Settlements

From 1750 to 1874

BY

J. J. CROOKS (Major)

Sometime Colonial Secretary of Sierra Leone

AUTHOR OF

A History of Sierra Leone

History of the Royal Irish Artillery

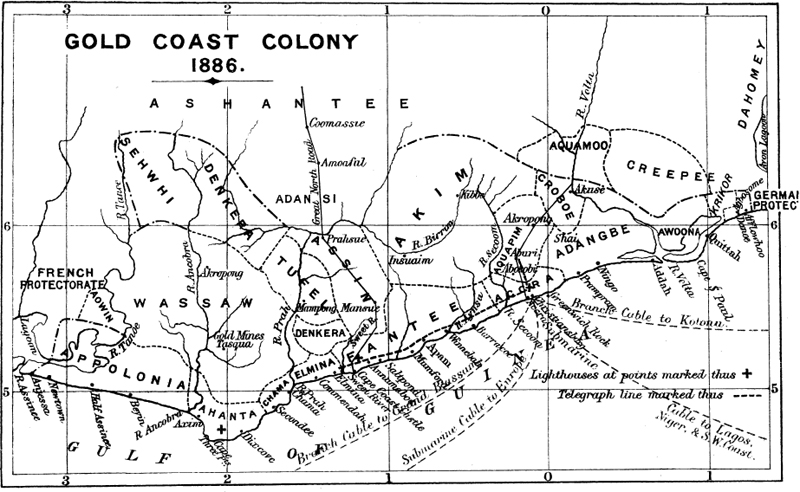

The African Companys Arms 1750

DUBLIN

BROWNE AND NOLAN, LIMITED

Branches: Belfast, Cork, and Waterford

1923

(ALL RIGHTS RESERVED)

FOREWORD

ALTHOUGH various books have been written giving a description of the Gold Coast, there is room, I think, for this volume, which is intended to cover the period from the formation of the last African Company of Merchants in 1750 until the conclusion of the third Ashantee War in 1874.

The British Settlements on the Gold Coast had a very chequered career; now they were under the Government jurisdiction, and again they were abandoned to the Merchants.

For the information comprised in this book relating to the Company of Merchants (17501820) I am indebted to the valuable Records of the English African Companies, deposited at the Public Records Office, London, where I received ready and useful help from the authorities. It is hoped that the events of most note reproduced here from these records* will give the reader an idea of the form of government on the Gold Coast in the days when the Forts were under the management and direction of a mercantile company.

Upon the historical matters relating to the government of the Settlements by the Crown, I have availed myself of the information contained in such State Papers as are open to public inspection at the Records Office, London, the Reports issued by the Colonial Office, and the House of Commons Papers.

Notwithstanding that the African Companys jurisdiction extended only over their Officers and Slaves, still at times we come upon instances where the guns of the Fort were fired upon the town, causing loss of life and the destruction of many of the native houses. And it may be added that the Company also exacted deference from Ashantee visitors on their passing the gate of the Fort as the following will show. Extract from a Letter* from Governor Smith to T. E. Bowdich, Esq., dated Cape Coast Castle, 17 August, 1817:

The day before yesterday an Ashantee man was guilty of a most daring insult to the Fort. On passing the gate, he was desired by the sentinel to take his cloth off his shoulders, but instead of complying, he turned round and struck him. The offender was instantly secured, and I ordered him to be put in irons. Last night, about nine oclock, the captain of the guard came to me to say that the sentry on duty had reported the Ashantee to have hung himself. The place in which he was, with others, confined was immediately opened, and he was found in a room adjoining to that in which the prisoners sleep, with his under-cloth attached to a beam not more than three feet high, and very tightly drawn round his throat, part of his body was lying on the ground, and it must have been by the most determined resolution that he succeeded in strangling himself.

The year 1782 saw English troops stationed on the Gold Coast for the first time. Early in February two Independent Companies disembarked at Cape Coast for the defence of the Settlements and the reduction of the Dutch Forts in the neighbourhood. On February 17th of that year an attack was made upon Elmina by a combined land and sea force, and continued till the 21st, when the British were repulsed with loss. The literature on the subject of the attack is scanty, due possibty to the dispatches sent to England in the sloop Alligator being thrown overboard when that vessel was captured by a French frigate and brought to Brest. Fortunately, duplicates of the Naval Commanders dispatches were sent by the cartel Mackarel. In March, 1782, Captain Shirley, in the Leander, ran down the coast, and without the assistance of the Independent Companies succeeded in taking five of the Dutch Forts.

The records of the European troops on the Gold Coast in these days do not make cheerful reading. The casualties amongst the Independents during their short-lived existence of less than three years were considerable. The total strength of the Companies on landing had been 200. In six months the force was reduced to 60. Besides the deaths that had occurred 39 men deserted to the Dutch, and 28 had been put on board a captured vessel. The two Companies were disbanded in 1783.

The following extraordinary cases of the infliction of Capital and Corporal Punishments make one shudder to think what the soldiers lot on Africs West Coast must have been in the seventeen-eighties:

In 1782, at Mouree Fort, near Cape Coast, a Private of the Independent Companies was, by his Captains order, blown from the muzzle of one of the guns.*

In this year also, at the Island of Goree, the Commandant ordered a Serjeant of the African Corps, who was charged with Mutiny, to receive 800 lashes. The Serjeant died shortly afterwards. The Commandant was tried for the murder and was hanged.

In 1821 an Act of Parliament was passed for abolishing the African Company of Merchants, and for transferring to the Crown all the Companys Forts and Possessions on the Gold Coast, which were to be placed under the government of Sierra Leone.

In March, 1822, Sir Charles Macarthy, Governor of Sierra Leone, arrived at Cape Coast Castle, and to provide for the defence of the Forts he formed the native troops in the service of the late African Company into a Colonial Corps, composed of three Companies, under the name and denomination of the Royal African Colonial Light Infantry. On the outbreak of the first Ashantee War in 1823, two European Companies of the late Royal African Corps were sent to Cape Coast to join the newly-formed Light Infantry, and in 1824 and 1825 the garrison of Cape Coast was further increased by reinforcements from England and the Cape of Good Hope. Owing to the frightful mortality among the European troops, the Government decided in January, 1826, that the Royal African Corps should in future be recruited either from the natives or the liberated Africans; and the custom of transferring to the Corps Deserters and Culprits from other Regiments Avas ordered to be discontinued. In the end of 1826 the few white troops who survived were withdrawn, and their place supplied by natives.