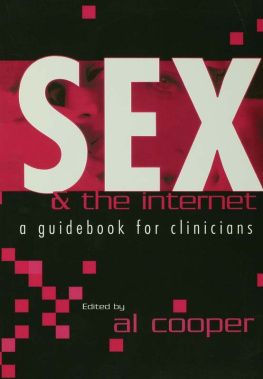

SEX AND THE INTERNET

SEX AND

THE INTERNET:

A Guidebook for Clinicians

Edited by

Al Cooper

First published 2002 by

Brunner-Routledge

29 West 35th Street

New York, NY 10001

Published in Great Britain by

Brunner-Routledge

27 Church Road

Hove, East Sussex BN3 2FA

Copyright 2002 by Brunner-Routledge

Brunner-Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group.

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Cooper, Al.

Sex and the Internet : a guidebook for clinicians / by Al Cooper.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 1-58391-355-6 (pbk.)

1. Sex addiction. 2. Computer sex. 3. Sex counseling. I. Title.

RC560.S43 C664 2002

616.8583dc21

2002018287

CONTENTS

| Albert Ellis |

| John Bancroft |

|

Al Cooper and Eric Griffin-Shelley |

PART I

POPULATIONS OF CONCERN |

|

Sandra Leiblum and Nicola Dring |

|

Michael W. Ross and Michael R. Kauth |

|

Mitchell S. Tepper and Annette F. Owens |

|

Robert E. Longo, Steven M. Brown, and Deborah Price Orcutt |

PART II

CYBERSEX PROBLEMS:

THERAPEUTIC CONSIDERATIONS |

|

Al Cooper, Irene McLoughlin, Pauline Reich, and Jay Kent-Ferraro |

|

David Greenfield and Maressa Orzack |

|

David L. Delmonico, Elizabeth Griffin, and Patrick J. Carnes |

|

Jennifer P. Schneider |

|

Nathan W. Galbreath, Fred S. Berlin, and Denise Sawyer |

PART III

OTHER AREAS OF SPECIAL INTEREST |

|

Al Cooper, Coralie Scherer, and I. David Marcus |

|

S. Michael Plaut and Karen M. Donahey |

|

Eric P. Ochs, Kenneth Mah, and Yitzchak M. Binik |

|

Azy Barak and William A. Fisher |

FOREWORD

The Internet is here to stay, and in the future it will most probably be much more widely used for psychological and clinical education than it is at the present time. The Internet is already used to disseminate a considerable amount of mental health information, to provide psychotherapy, and as an adjunct to more traditional forms of psychotherapy. I predict that this trend will steadily increase in the coming years. At the psychological clinic of the Albert Ellis Institute in New York, we have started using the Internet for personal sessions of rational emotive behavior therapy (REBT) with both American and international clients. We have found this type of usage to be so effective that we will soon expand it considerably.

Sex, relationships, and family involvement on the Internet has greatly widened in recent years, and will most probably continue to do so. This kind of participation has its problems and dangers, as shown in some of the chapters in this book. But it also has distinct advantages for communication that are not readily available through other media. Both private and public presentations in these areas provide fascinating alternatives to other means of communicating.

In Sex and the Internet: A Guidebook for Clinicians, Al Cooper and his collaborators present a wealth of relevant material about the Internet's facilitation of sex, relationships, and family matters. The various chapters describe the Internet's present coverage in these areas, as well as its future possibilities. They include a surprising amount of enlightening material that has not previously been available in book form. Readers will gain unusual knowledge of the Internet itself and how it can beneficially be adapted to dealing with significant sexual and relationship issues. Read it and enjoy!

Albert Ellis, Ph.D.

PREFACE

One of the most fundamental conclusions from Alfred Kinsey's research of more than 50 years ago was that human sexuality is extraordinarily variable in its expression. Basic biological mechanisms interact with a variety of sociocultural factors to shape a bewildering array of patterns of sexual response. This interaction between biology and culture is poorly understood, but the capacity to associate sexual response with diverse stimuli, based on the principles of learning, is fundamental, and sociocultural influences can both encourage and discourage, intentionally or unintentionally, what stimuli are involved.

When we consider the society that Kinsey studied, we can see how easily sexual expression was distorted by socially driven guilt and anxiety and by the social promotion of sexual stereotypes, fostering problematic power relationships between men and women and ostracizing those with unconventional sexual values. The negative consequences, to both the individual and society, were plain to see. But have we been moving toward a better socially determined pattern of sexuality since Kinsey's time? That is also questionable. The past 50 years have seen social change at a rate and extent unprecedented in history. A number of changes that are clearly to be welcomed have combined with other changes of less certain advantage to impact sexuality at the end of the 20th century, and we enter the 21st century far from certain where we are heading.

One fundamental part of this changing picture has been called the triumph of the individual over society (Hobsbawm, 1997). People have increasingly been giving their own individual welfare and personal development top priority in their lives. Primary allegiance to the family is becoming a thing of the past. While traditional marriage has been taking a beating, at least as a long-term commitment, we have seen the impact of the women's movement on the structuring and negotiating of what have been called pure relationships. The

Next page