The publisher and the University of California Press Foundation gratefully acknowledge the generous support of the Simpson Imprint in Humanities.

The Kingdom of Rye

A BRIEF HISTORY OF RUSSIAN FOOD

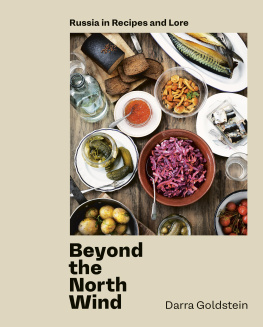

Darra Goldstein

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS

University of California Press

Oakland, California

2022 by Darra Goldstein

This book was prepared with the assistance of the Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow.

Excerpt from The Collected Works of Velimir Khlebnikov: Volume 3Selected Poems , translated by Paul Schmidt, edited by Ronald Vroon, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, copyright 1997 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Excerpt from Broccoli and Other Tales of Food and Love by Lara Vapnyar, copyright 2008 by Lara Vapnyar. Used by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Goldstein, Darra, author.

Title: The kingdom of rye : a brief history of Russian food / Darra Goldstein. Other titles: California studies in food and culture; 77.

Description: Oakland, California: University of California Press, [2022] | Series: California studies in food and culture; 77 | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021045269 (print) | LCCN 2021045270 (ebook) | ISBN 9780520383890 (hardback) | ISBN 9780520383906 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : Food habitsRussiaHistory. | FoodRussiaHistory. | Cooking, RussianHistory. | RussiaSocial life and customs.

Classification: LCC GT 2853. R 8 G 65 2022 (print) | LCC GT 2853. R 8 (ebook) | DDC 394.1/20947dc23/eng/20211015

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021045269

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021045270

Manufactured in the United States of America

31 30 29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For my sister, ARDATH WEAVER , whose creativity and support have guided me all these years

, .

If the rye ripens, its a good year.

RUSSIAN SAYING

!

What I wouldnt give for a piece of black bread!

ALEXANDER PUSHKIN , A Journey to Arzrum (1835)

Contents

Illustrations

MAP

FIGURES

MAP 1. Russia and places mentioned in this book.

Preface

In my family, Russia was a place to escape from. My grandparents had fled in the early twentieth centuryI never knew exactly whenand they refused to share stories of their past. So the country loomed large in my imagination. I tasted it in my grandmothers beet kvass, in her sorrel soup, in her stuffed cabbage.

In college, I decided to study Russian to learn more about this beguiling place. In those days we werent taught oral proficiency; we entered the language through grammar and literature. I struggled through texts that refused to yield their meaning; then suddenly Id happen upon a passage describing food, and the language would magically open up to me. These passages occurred surprisingly often. I absorbed the sentences first as sensations, even before I understood the actual words. Only after Id figuratively savored the dishes did I look up the unfamiliar words in the dictionary to memorize their exact meaning.

One literary meal led to another. My language skills improved, and I longed to visit Russia. The mere thought of my traveling there horrified my grandmother, but in 1972 I went nonetheless. My first breath of Soviet air immediately dispelled any romance: the place smelled of overcooked cabbage. The gray food I encountered matched the dingy surroundings. This wasnt the French-inflected haute cuisine I had encountered in nineteenth-century literature; nor was it the rustic food of the peasantry. This was Soviet food in an era when few ingredients were available. On that first visit I didnt taste the famous fish pie, kulebiaka , so erotically described by Chekhov, or the plump pancakes known as bliny that Gogols hero Chichikov downs three at a time after dipping them in melted butter. But I thrilled to the flavors of coriander-studded rye bread, to open-faced buns filled with sweetened farmers cheese, to Siberian dumplings laced with vinegar and mustard, to half-sour cucumbers and golden, brined cloudberries. Only later, after I broke through the surface (and the rules about what foreigners could and could not do), did I finally begin to experience all the vibrant flavors of Russia.

Once I got to graduate school, I intended to write my dissertation on food in Russian literature. But I was ahead of the times. In 1974 hardly anyone in American academia took food seriouslycertainly not my Stanford professors, who maintained I would have no future with such a trivial pursuit. So I focused instead on Russian modernist poetry (which I dont regret). But I never abandoned my subversive idea of writing about Russian food. As I studied for my qualifying exams, I jotted down every reference to food I encountered over two centuries of Russian literature. Many of these quotations eventually found their way into my first cookbook, A la Russe: A Cookbook of Russian Hospitality , which came out in September 1983, just as I started teaching Russian literature at Williams College. The book may have begun as a metaphorical thumbing of my nose at the stuffy attitudes of my professors, but it became a response to the year when Id taken a break from grad school, working instead for the United States Information Agency in Russia. I served as a guide for the exhibition Agriculture USA, an outcome of the 1958 cultural agreement between the US and the USSR. The exhibitions presentation of American agricultural bounty was not apolitical. It was a finger in the eye to a country suffering severe food shortages heightened by the Cold War. I had a fleeting but nasty encounter with the KGB, made worse by a debriefing by US State Department security, and by the end of my ten-month stint, I was ready to give up Russian studiesno matter that Id already invested so much. But something pulled me back, and that something was Russian hospitality. Ordinary people asked me to dinner. We crowded around tiny tables, eating with mismatched plates and forks in tiny, rudimentary kitchens, and the food was delicious. My pursuit of things Russian was saved by the generosity of all the people who opened their homes to me, often at considerable risk, to share whatever they could put together from the scarce resources at hand. My book was my thank-you note.

Over the years, as I traveled throughout the Soviet Union and then Russia, my interest in Russian food only deepened. I was still working in archives, researching Russian poetry, but my real aim was to understand Russian food culturethe origins of dishes, the role of the traditional Russian stove, the superstitions surrounding preparation, the influence of the Orthodox Church, gender roles in the kitchen, etiquette at the table, the introduction of foodstuffs from East and West and how Russians adapted them to their own taste. It was a pleasure and a passion to uncover Russias most elemental flavors, the ones that stretch back over a thousand years, to try to define the basics of the cuisine.

![Goldstein Darra - Fiery Ferments [eBook - Biblioboard]: 70 Stimulating Recipes for Hot Sauces, Spicy Chutneys, Kimchis with Kick, and Other Blazing Fermented Condiments](/uploads/posts/book/201436/thumbs/goldstein-darra-fiery-ferments-ebook.jpg)