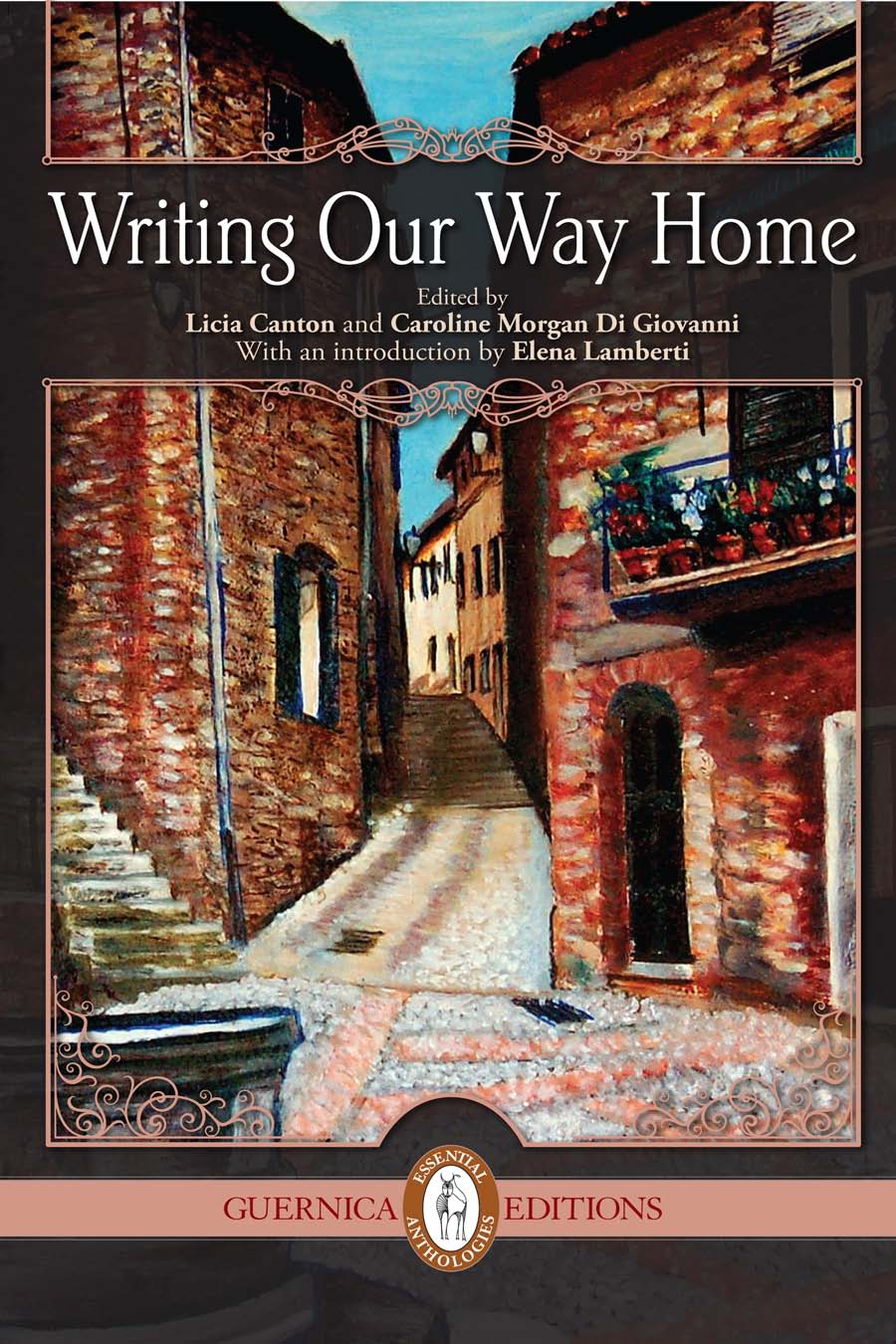

Writing Our Way Home

Edited by Licia Canton and Caroline Morgan Di Giovanni

With an introduction by Elena Lamberti

Guernica Essential Anthologies Series 5

Toronto Buffalo Lancaster (U.K.) 2013

In memory of

Anna Carlevaris (1954-2012)

Giovanni Costa (1940-2011)

John G. Madott (1918-2011)

al di l di quel vasto orizzonte

c un lungo acciottolato di memorie

from the poem Ricordi by Giovanni Costa

Contents

Introduction

Elena Lamberti

I REMEMBER WELL MY JOURNEY FROM Bologna, the city where I live and work, to Atri, in Abruzzo. Thats where, in June 2010, the thirteenth biennial conference of the Association of Italian Canadian Writers was held. I travelled on a slow train along the Adriatic Coast. The train stops in Pineto and, from there, someone can pick you up by car or you have to wait for the right bus. It was a typical hot, Italian summer day. On that train, I couldnt help but think that even in 2010 Italy was still a country travelling at different speeds, metaphorically and literally. Travelling North to South and vice versa, Italy moves much faster along its western corridor than along the eastern one. Never mind how long it takes and how slow it is to travel from coast to coast: the railway lines that connect the Tyrrhenian Sea to the Adriatic have been the same for ages. There, through time, it is the railway that stands still, while the surrounding territory moves. A typical Italian paradox.

I was thinking of the peculiar mapping of Italian railways while going to a conference whose theme was connected to the idea of travelling: Writing Our Way Home or, in Italian, Il viaggio di ritorno.

That title would immediately render the idea of both a real and an imaginary journey, combining different landscapes and suggesting an open idea of Home, to be questioned and assessed at the symposium. I would be listening to stories of Italians who arrived in the Nuovo Mondo long ago. If truth be told, I was afraid of those stories or, rather, I was afraid I would have to listen to stories told too many times: redundant stories of Italian immigrants abroad, grown into a self-referential myth blurring the intensity of the historical archetype which had originated them. Stories that felt more and more distant from my changing self and from my modern, changing world Italy in 2010. Dont get me wrong, I have a deep respect for the stories and history of all those who, for different reasons, were forced to leave their Motherland. (When you are forced to leave, you never leave a country; you leave a Motherland; a Patria not a nation). My respect is born out of my historical sense and my cultural memory. It is rooted in my personal knowledge of many Italian immigrants abroad whose lasting trauma and pain are also well known to me. However, I must confess that, on my way to Atri, I also couldnt help but think of the many times I had felt subtle impatience and a pervasive frustration in seeing that intense trauma imploding in a series of narrative clichs. These narrative clichs have shaped the two main characters of the early immigrants commedia (or perhaps tragedia) dellarte: the victim (the Italian immigrant) and the persecutor (the new country). A Motherland, the old country cannot be a stepmother, even if it can no longer hold us close as a mother does.

Having said this, I recognize the important role of Italian-Canadian literature. Through time, determination and talent, Italian-Canadian writers have established a cultural and artistic heritage which matters to both Canada and Italy. I remember the work of Raffaele Cocchi, a colleague at the University of Bologna, who was one of the first to bring new and emerging Italian-Canadian voices to our attention as early as the 1980s. Although he passed away unexpectedly in 2004, his lessons remain. His contributions to the Fondazione Giovanni Agnelli Altreitalie, and to CISEI Centro Internazionale Studi Emigrazione Italiana are still landmarks in the study of the culture and history of Italians abroad. He also taught us how to appreciate those new works not simply to acquire sociological knowledge about Italian emigration, but more importantly to value their intrinsic aesthetic and literary merits. Raffaele Cocchi taught us to be passionate about Italian-Canadian voices while not exempting us from a critical response and appreciation. Of course the immigrants stories and nostalgia are traditional tenets of Italian-Canadian literature, but they can no longer be narrated in the same ways. The impatience and frustration alluded to above did not originate from a lack of appreciation for traditional themes in Italian-Canadian literature, but rather from my desire to see that literature grow and bloom. I want to see it change and face new contingent challenges because we change through time and history is always in the making.

In other words, as an Italian reading Italian-Canadian literature in Italy (the motherland), I maintain that todays Italian-Canadian writers could contribute much more to the literary community which includes Italians, Canadians and all those who think that literature plays a fundamental role in our global and globalised brave new world. History has changed rather quickly: Italy is now the promised land for newcomers forced to leave their own motherland. Italy is to these new immigrants what Canada was to Italian immigrants not too long ago. It does not matter that, in fact, Italy IS NOT Canada. Yes, its an old story: history repeats itself. What if my own old immigrants, as well as their literary children, those Italians who have been so successful, who have made it, help us (old and new Italians) to find ways of better understanding each other, our stories and our histories? After all, our Italian immigrants have been able to overcome, through literature too, all those material, cultural and social obstacles that Italian-Canadian writers and artists have so well described in their novels, poems, paintings, songs and movies. The time has come to speak in the present and for the present. It is time to listen to second and third generation children who were born in Canada and who have a different understanding of home and Motherland. That does not mean to deny history. On the contrary, it means using history wisely and speaking to Italy from Canada as Italian immigrants who suffered the same experiences not too long ago, but who were successful nonetheless. Who better than the sons and daughters who have experienced the trauma of forced immigration can talk to a mother, a nation, Italy, which is now playing the role of the persecutor in the literary works written by new X-Italian writers? Yes! There are new writers in Italy. They were not born in Italy, but they have a sense of belonging there. In their stories, too, there are homes, mothers and stepmothers, countries and nations. History repeats itself, but sometimes well, often in reverse.

Travelling on slow trains gives one time to think. Italian immigrants in the world, journeys from and to the motherland, Raffaele Cocchi and his lessons, newcomers to Italy: thats what I reflected on as I travelled from Bologna to Pineto. Once in Atri, I met the old and new voices of Italian-Canadian literature. I was comforted. My worries disappeared. I thought of Raffaelle Cocchi even more. He would have been very happy in Atri and not just because of the superb location and memorable meals. He would have been happy to witness the literature he loved so much reaching a new prime and moving on. Looking back, I dare say that the gathering in Atri was a turning point in the history of the Association of Italian Canadian Writers. As a consequence, it was a turning point in the history of the reception of Italian-Canadian literature outside of Canada, and especially in Italy. Yes, we want the best for what we love most! Atri was a good moment for the AICW: it revealed a mature literary group which is still blooming not only in numbers (members), but mostly in themes, content, ideas. Certainly, the immigrants stories are still being told (it goes without saying!), but nostalgia now has a different flavour. Italian-Canadian writers and scholars have assaulted, so to speak, the clich, bringing new registers and innovating the intergenerational dialogue. It is now possible to laugh about old grievances: not to diminish them, but to turn pain into energy. Its no longer survival: its a new, full, happy and tragic life.