ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My grateful thanks to the following for their help and support: Alan Watts, Clive Davis, Marcus Lester, Adrian Cypher, David Wakefield, Peter Davison, Steve Lynch, Paul Willis, John W Henderson, Rob Campbell, Iain Carr, Ken Beresford, Scott Whitehouse, Martin Aidney, Tony Jennings, my publisher and, of course, Linda and Jess Dyer.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

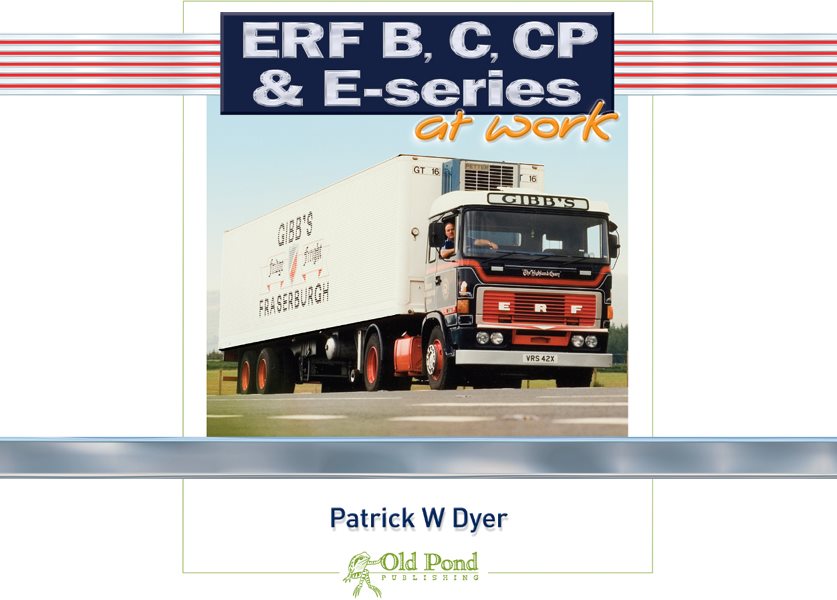

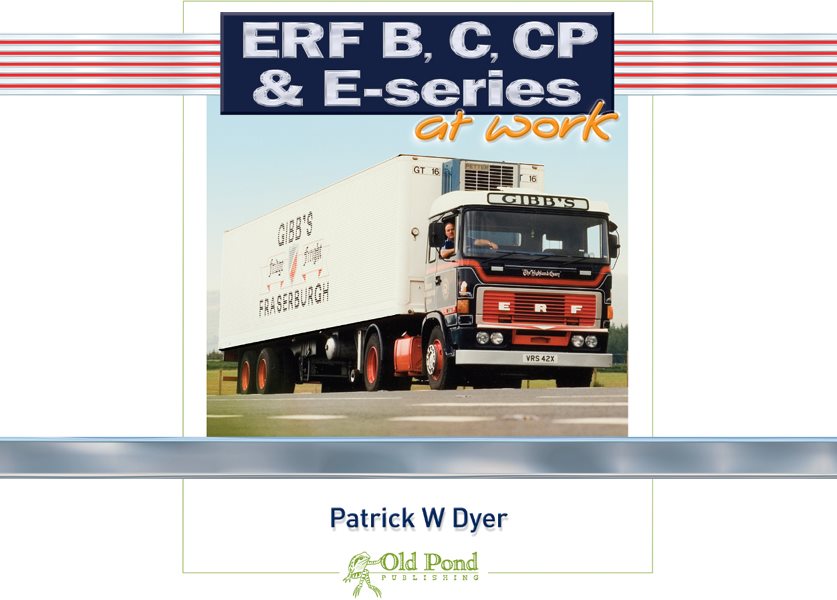

Patrick Dyer, born in 1968, grew up during one of the most notable and exciting periods of development for heavy trucks and the last of the real glory days for trucking as an industry. This is reflected in his subject matter. Previously published in his growing Trucks at Work series are: Scanias LB110, 111 and 141; DAFs 2800, 3300 and 3600; Fords Transcontinental; Volvos F88 and F89, followed by the F10 and F12; and Seddon Atkinsons 400, 401 and 4-11 and Scania 112 and 142.

DECLARATION

There were at least six recognised methods of measuring engine output for trucks during the period covered by this book. Manufacturers and magazines often quoted different outputs for the same engine using BS.Au, SAE, DIN and ISO systems, some gross and some net, much to everyones confusion. Therefore, for clarity, only the figures quoted by ERF at the time are used throughout this work.

DEDICATION

This one is for Graham Baker, a good friend and self-confessed Gardner fan, without whose help and knowledge my Volvo F12 restoration would never have been finished. Thanks, Graham!

By Reg Crawford

I write this foreword with a great deal of humility and more than a little trepidation out of respect for ERF as a manufacturer that became a powerful symbol and representative of the Great British Truck Industry, and for Peter Foden CBE, its late Chairman, and his management team who I worked for and with during a brief period in the 1980s. My day job for many years now has been working as a business writer. I write and indeed ghost-write editorial articles and other material on the subject of trucks, road transport and the people who work in the industry. It is a privileged position that has given me access, by necessity, to what is often proprietary information and people at all levels. That is why I have only been published under my own by-line on a few occasions and then mostly in in-house articles and journals.

When Patrick Dyer approached me with a request to write this foreword, I was somewhat bemused as all my working life I have preferred to work in the background, believing that, as I am paid to write about the achievements of others, my customers and editors are, quite rightly, not interested in my opinions. At first, I was minded to turn down Patricks request. However, on reflection, I decided to accept and present my personal observations for scrutiny in this excellent book.

The period covered in this book encompasses the launch of the B-Series in 1974 to the years immediately after the launch of the E Series in 1986. In that time ERF the company changed and grew in stature and its products developed into serious competition for the continental manufacturers who by then had successfully made huge inroads into the indigenous truck parc in all sectors from 16-tonners to multi-axle rigids and the big-hitter tractor units. Their success was down to building what customers needed as businessmen and women and what drivers wanted:

A consistent level of service, good back-up and a comfortable workplace for the driver usually with a synchromesh gearbox. Until the advent of the E-series, ERF had tended to rely on the other, equally important operational virtues of good fuel economy, good payload and a long working life. In fact, ERF was known rather disparagingly by its German, Dutch and Swedish rivals as the no-nonsense builder of a gaffers truck. As Patrick Dyer points out in these pages, that meant a solid, dependable, no-frills workhorse that delivered a good payload. But things were about to change.

In the mid-1980s, the company made a quantum leap, first with the CP and then with the E-series. ERF began to offer trucks that appealed to drivers and yet still delivered those qualities that had ensured the marques appeal to hauliers and national fleets for so many years.

In my opinion, the success of the E-series was largely down to the foresight and relentless drive of the companys charismatic Sales & Marketing Director, Bryan Hunt. His enthusiasm for change and a positive turnround in the companys fortunes, both fiscal and in terms of its standing and repute as a manufacturer that could stand up to the might of the Europeans, carried his co-directors with him. Particularly so, Peter Foden, who was very much a champion of change and growth. In 1985 and 86, Bryan Hunt charged at any remaining naysayers in the wood-panelled offices of Sun Works and drove through changes in the product range that made it vastly more appealing to new customers as well as die-hard traditionalist hauliers, the bedrock of the customer base, who had unstintingly supported ERF through good times, bad and indeed very bad. I saw first hand how he would professionally and logically present the options to his colleagues. His background was as a consultant and a director at Cummins Engine Company and Solar Turbines. He was not an engineer but he knew how to persuade the engineering team and the board to accept that the product range needed to be rationalised. Gardner and Rolls-Royce engines continued to be offered, but were not in the preferred spec. That rationalisation resulted in the CP range, followed by the E-series, and was patently good both for the business and its customers. Rationalisation of the driveline down to a simple and at the time highly controversial powertrain of Cummins, Eaton and Rockwell, meant that the manufacturing side of the business benefited from the cost reductions associated with reduced inventories and fewer parts in build lists reducing the number of snags faults found on inspection at the end of the build line. Customers could benefit from the reduced parts inventory if they ran their own workshops, and efficiencies were gained in training workshop technicians to service and repair a narrower range of components and assemblies. If a CP or E-series truck broke down, and if it was equipped with the rationalised driveline, the likelihood of the repairing dealer having the parts in stock increased exponentially. All in all, the CP and E-series represented an easier-to-understand and simpler, more modular concept that appealed to many operators who ran foreign-built trucks. It became a virtuous circle and ERF won many new customers as a result. So much so that, at a press briefing, cheekily held at Thame, the home of DAF Trucks in the UK in 1987, Peter Foden announced that ERF now had over 3,000 customers on its books.

The understated Built in Britain badges on the cab tilt lock handles of the E-series were a tangible demonstration of ERFs core identity. It was a company and a brand that successfully offered its patriotism and Britishness as one of its unique selling points. It appealed to customers, suppliers and employees alike. With the non-rusting sheet moulded compound plastic cab, its panels pressed by ERF Plastics at nearby Biddulph, and British Steel chassis frame rails, it was positioned as the epitome of the British underdog company battling it out with the dark forces of the continental manufacturers. The truck media were usually pretty friendly and forgiving of ERF and enjoyed playing along with the underdog theme when it suited.