To my parents, Yuri and Musa Goldberg

CONTENTS

ix

xiii

PART I

HYPOCHONDRIA OF THE HEART: NOSTALGIA, HISTORY AND MEMORY

PART 2

CITIES AND RE-INVENTED TRADITIONS

PART 3

EXILES AND IMAGINED HOMELANDS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Nostalgia is not only a longing for a lost time and lost home but also for friends who once inhabited it and who now are dispersed all over the world. I would like to thank writers and artists whose friendship inspired me as much as their work: Maya Turovskaya, Dubravka Ugresic, Ilya Kabakov, Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid. I am grateful to my colleagues, scholars and friends who read portions of the manuscript in spite of our collective shortage of time: Greta and Mark Slobin, Larry Wolff, William Todd III, Donald Fanger, Richard Stites, Evelyn Ender and Peter Jelavich. I began to develop the idea of writing about nostalgia while on a Bunting grant from 1995 to 1996, and benefited from the discussions at the Institute. The first chapters of the future book were presented at the Conference on Memory at the Center for Literary and Cultural Studies at Harvard in 1995 and at the memorable meeting in Bellagio in April 1996. I am grateful to the organizers, Richard Sennett and Catherine Stimpson, as well as to its participants for their comments and remarks. Two summer IREX grants allowed me to complete the research on my project. Finally, a Guggenheim fellowship and sabbatical from Harvard University in 1998 and 1999 permitted me to write the book. My participation in various international conferences helped challenge and shape my ideas: the Conference on Soviet Culture in Las Vegas in 1997, the Conference on Myth and National Community organized by the European University of Florence and the discussions and lectures at the Central European University of Budapest in summer 2000. My collaboration on the board of the ARCHIVE organized for the study of ex-Soviet immigrant culture in the United States and many long conversations with Alla Efimova and Marina Temkina inspired me to begin my interview project on immigrant homes. Larisa Frumkina and the late Felix Roziner inspired me in that work and shared their immigrant souvenirs and stories with great generosity.

Each city I visited and described became my temporary home, at least for the duration of the chapter. In Petersburg I am grateful to Oleg Kharkhordin, a scholar of friendship and a good friend; OlesiaTurkina and Victor Mazin for artis tic guidance; Victor Voronkov and Elena Zdravomyslova for introducing me to their project on the "free Petersburg"; Nikolai Beliak for sharing dreams and masks of the Theater in the Architectural Environment; and Marieta Tourian and Alexander Margolis for being the best Petersburg guides. My high school best friend, Natasha Kvchanova-Strugatch, brought hack some not-so-nostalgic memories of our growing up in Leningrad. In writing on Petersburg I benefited from the work of Eua Berard, Katerina Clark and Blair Ruble. In Moscow I enjoyed Masha Gessen's hospitality, political insight and excellent cooking. Thanks to all my Moscow friends who reconciled me to their city and even made me miss it: Masha Lipman and Sergei Ivanov, Daniil Dondurei, Zara Abdullaeva, Irina Prox- orova, Andrei Zorin, Joseph Bakshtein, Anna Al'chuk and Alexander Ivanov. Grig- ory Revzin provided necessary architectural expertise. Masha Lipman shared wisdom and integrity and good humor; Ekaterina Degot', radical visions in art and politics. Alexander Etkind was a great intellectual companion and friend on all continents.

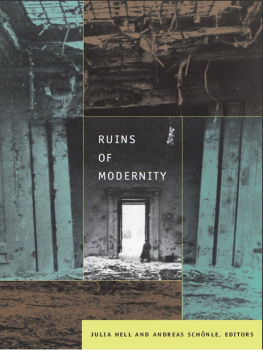

In Berlin I found a perfect home in the apartment of my Leningrad friend, Marianna Schmargen. My Berlin guide was a scholar and friend, Beate Binder, who showed me the best ruins and construction sites. Thanks also to Dieter Axelm-Hoffmann, Sonia Margolina and Karl Schlogel, Klaus Seghers, Georg Witte and Barbara Naumann. In Prague I enjoyed the hospitality and insight of Martina Pachmanova, and in Ljubljana the wisdom and good company of Svetlana and Bojidar Slapsak.

To my friends and fellow travelers who shared with me their longing and aversion to nostalgia: Nina Witoszek, Dragan Kujundic, Sven Spieker,Yuri Slezkine, Giuliana Bruno, Nina Gourianova, Christoph Neidhart, ElenaTrubina, David Damrosch, Susan Suleiman, Isobel Armstrong and Eva Hoffman, whose books inspired me long before our meeting. Thanks to Vladimir Paperny for real and virtual travels and for the photographs, and to Boris Greys for heretical discussions about absolutes.

I am enormously indebted to all the photographers who shared with me their pictures and their visions, especially Mark Shteinbok, Vladimir Papernv and Mika Stranden.

It wouldn't be worth writing books were it not for my students, who were my first and most attentive readers and critics. Julia Bekman gave invaluable editorial suggestions and together with Julia Vaingurt advised me on subjects ranging from Mandelstam's poetry to Godzilla movies. To my other readers and reseach assistants: David Brandenberger, Cristina Vatulescu, Justyna Beinek, Julia Raiskin, Andrew Hersher and Charlotte Szilagyi, who graciously took care of all the last-minute loose ends. Our graduate workshop "Lost and Found" helped us all to find out what we didn't know.

I am grateful to Elaine Markson, who encouraged and inspired me throughout, to my editor at Basic Books, John Donatich, who believed in the project for as long as I did and shared with me his own nostalgias. I am grateful to Felicity Tucker for her gracious help in putting the book together, and to the most patient and intelligent copyeditor, Michael Wilde.

Finally, special thanks to Dana Villa, who persevered against all odds and shared with me everything from Socrates to the Simpsons, and more. And to my parents, who never made a big deal out of nostalgia.

INTRODUCTION

Taboo on Nostalgia?

In a Russian newspaper I read a story of a recent homecoming. After the opening of the Soviet borders, a couple from Germany went to visit the native city of their parents, Konigsberg, for the first time. Once a bastion of medieval Teutonic knights, Konigsberg during the postwar years had been transformed into Kaliningrad, an exemplary Soviet construction site. A single gothic cathedral without a cupola, where rain was allowed to drizzle onto the tombstone of Immanuel Kant, remained among the ruins of the city's Prussian past. The man and the woman walked around Kaliningrad, recognizing little until they came to the Pre- golya River, where the smell of dandelions and hay brought back the stories of their parents. The aging man knelt at the river's edge to wash his face in the native waters. Shrieking in pain, he recoiled from the Pregolya, the skin on his face burning.