"Lucas, let me show you how bugs can tell a story of clean water," I say to my little brother, wiggling my eyebrows. He hates that.

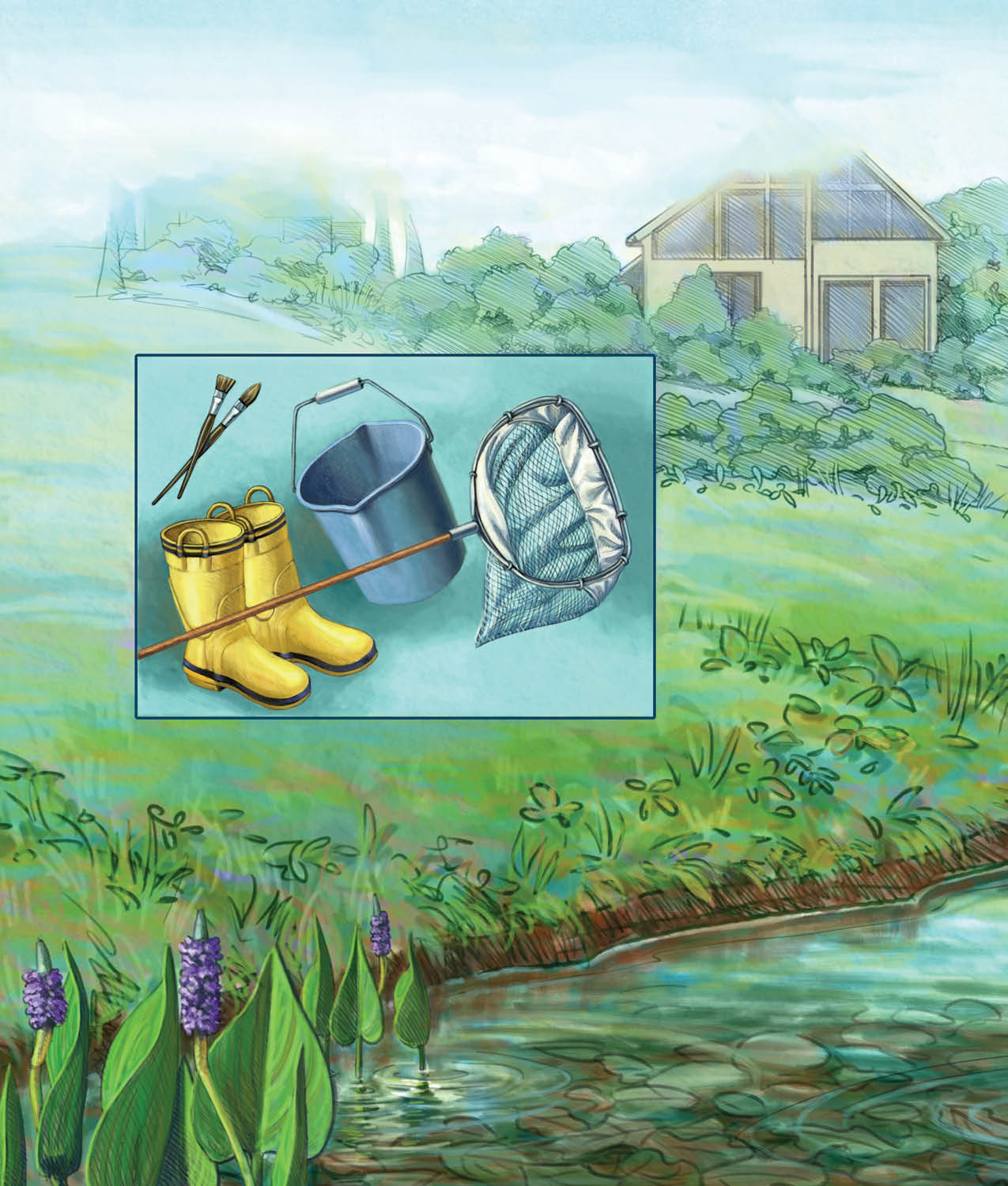

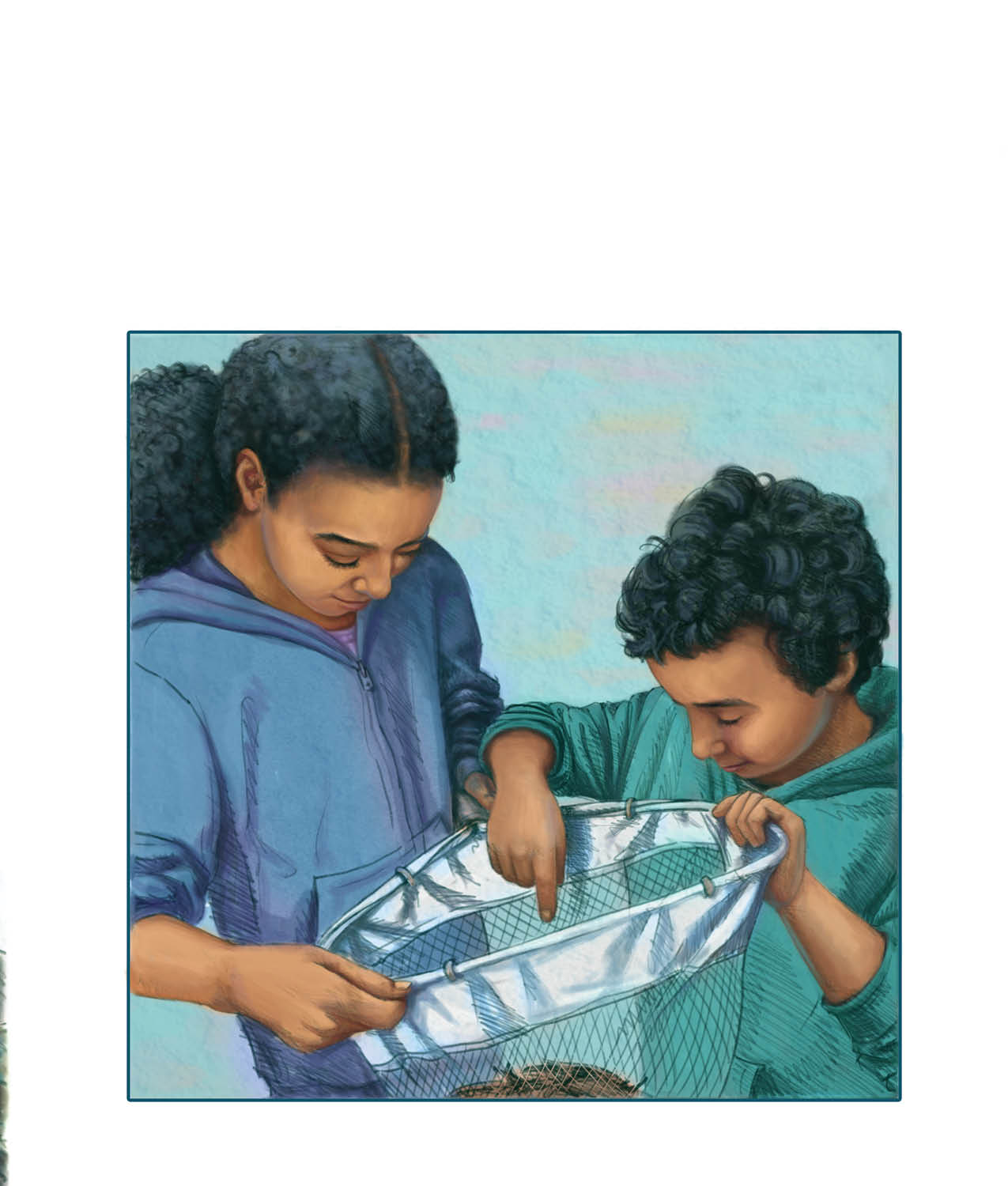

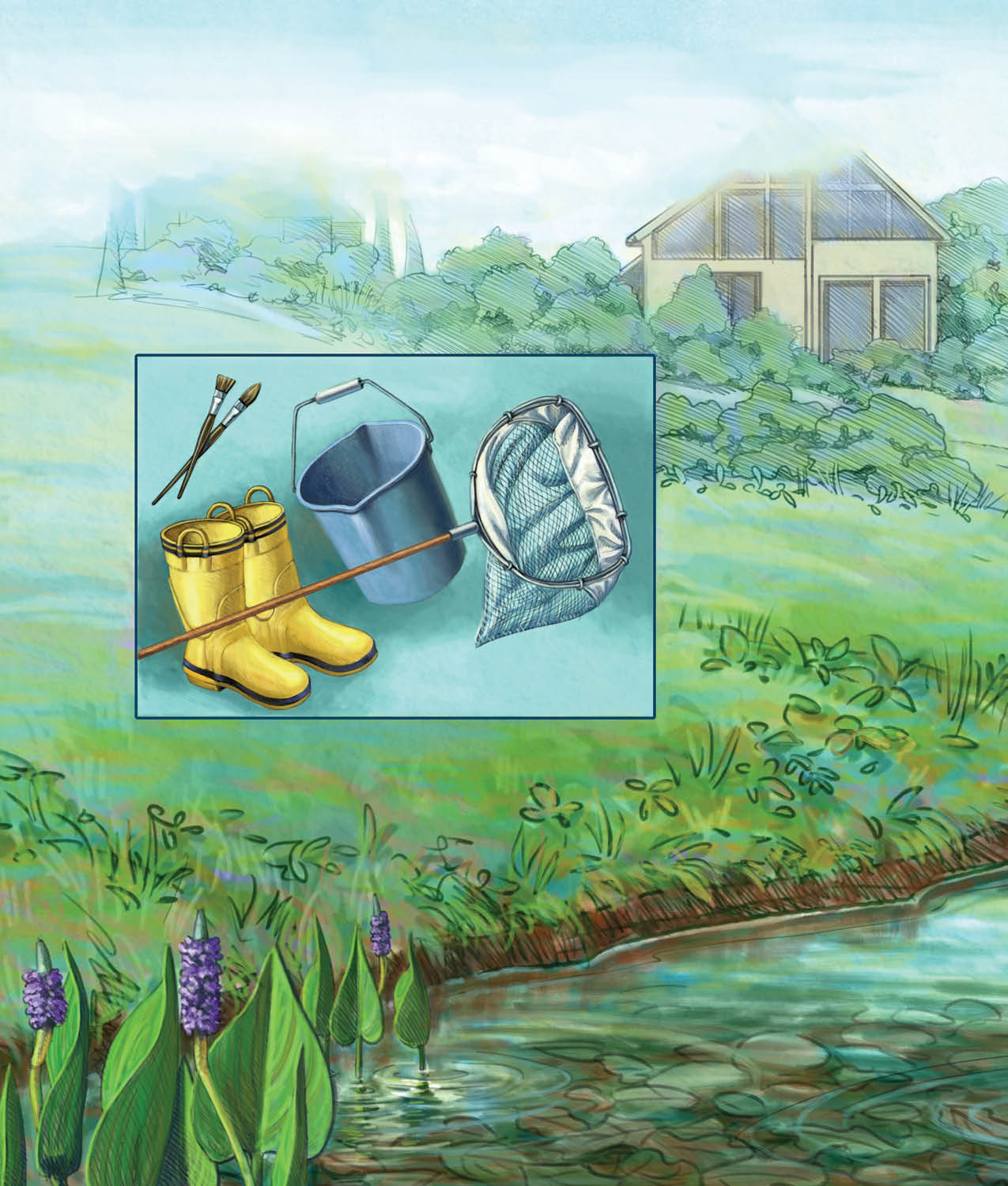

Lucas rolls his eyes but follows me to the house. We grab the same tools that scientists use: rubber boots, a net, a bucket, and small paintbrushes.

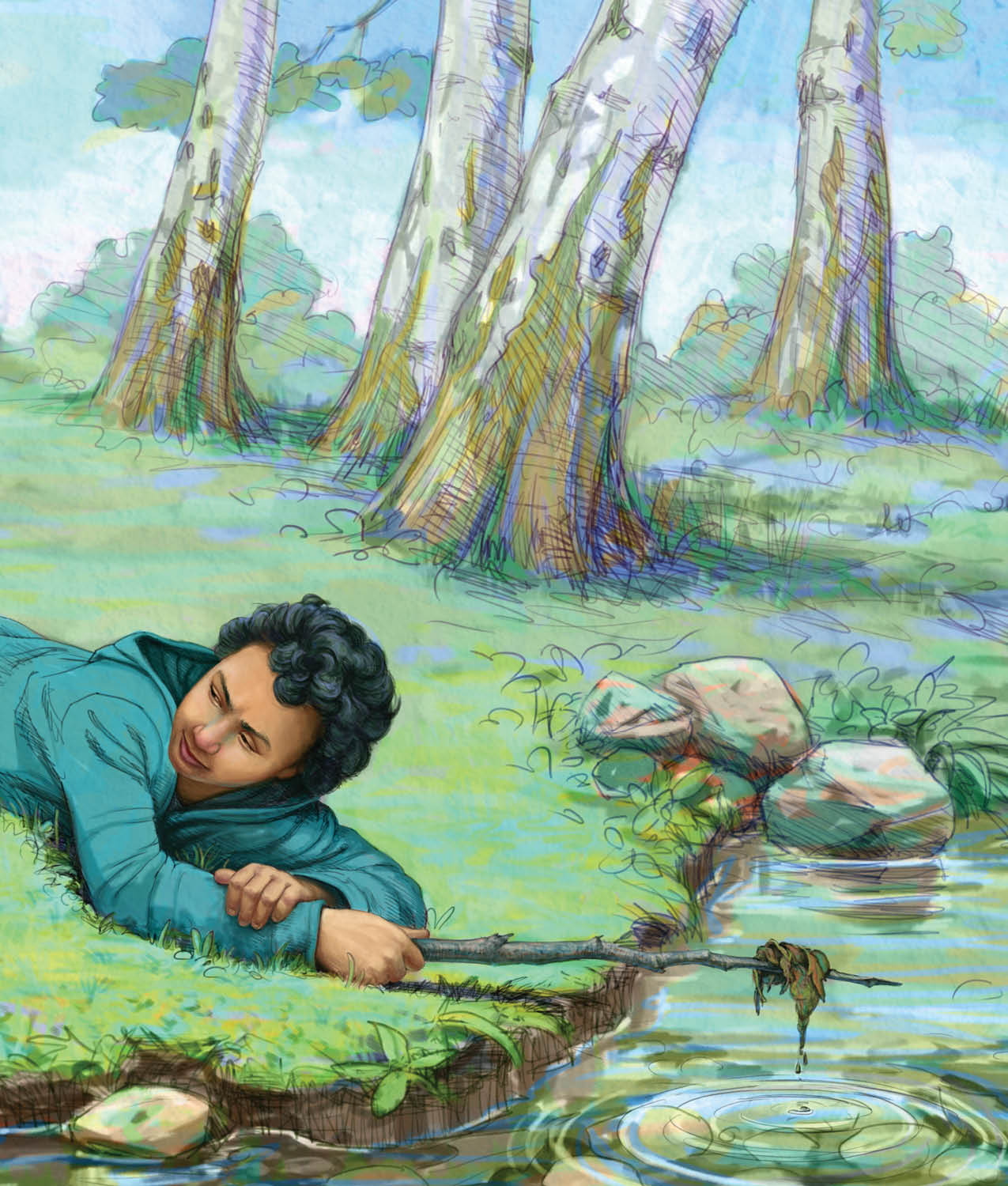

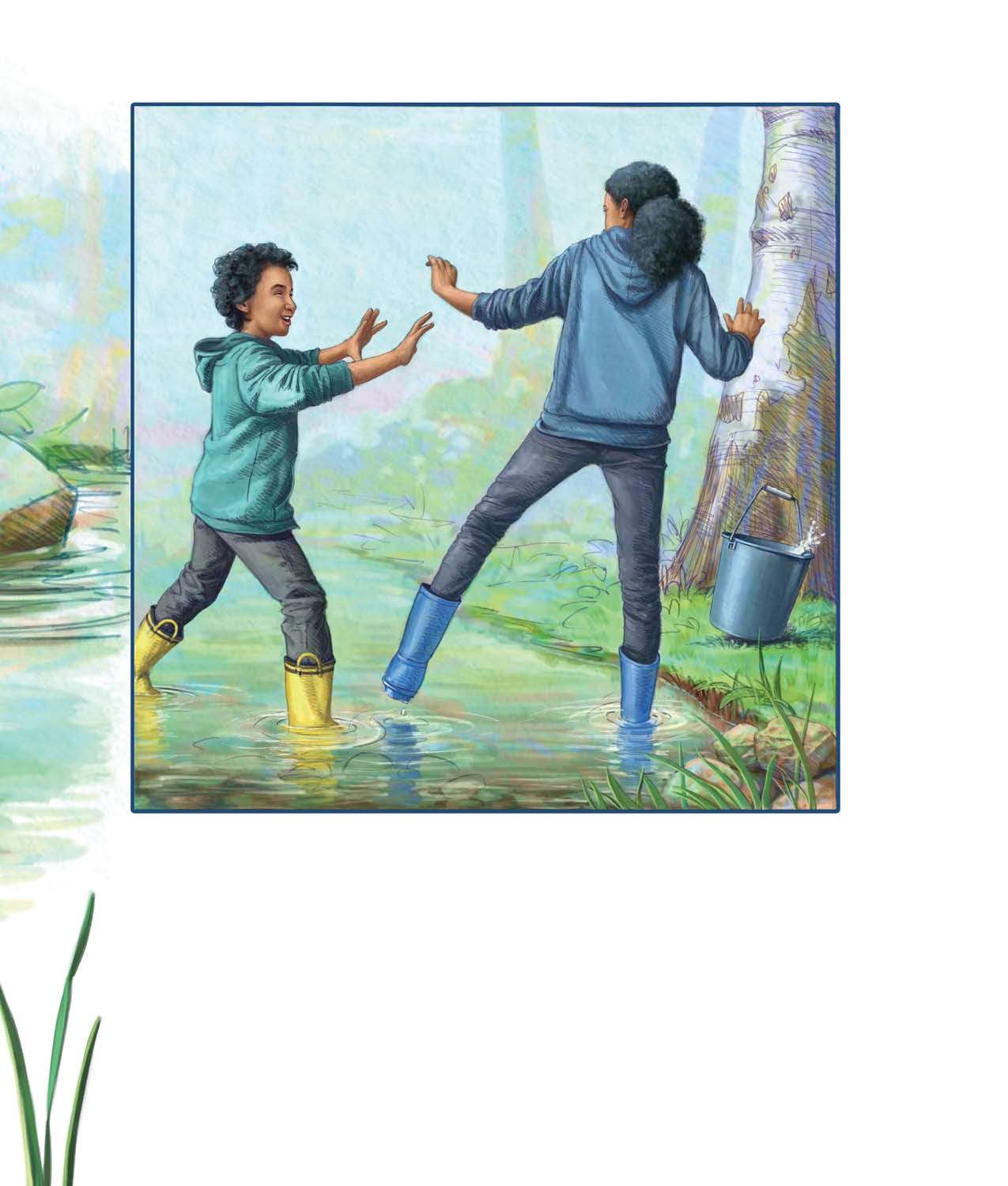

I splash water into our bucket and plop it next to a tall sycamore tree. Quickly, I spin around before Lucas can push me in. That water is cold!

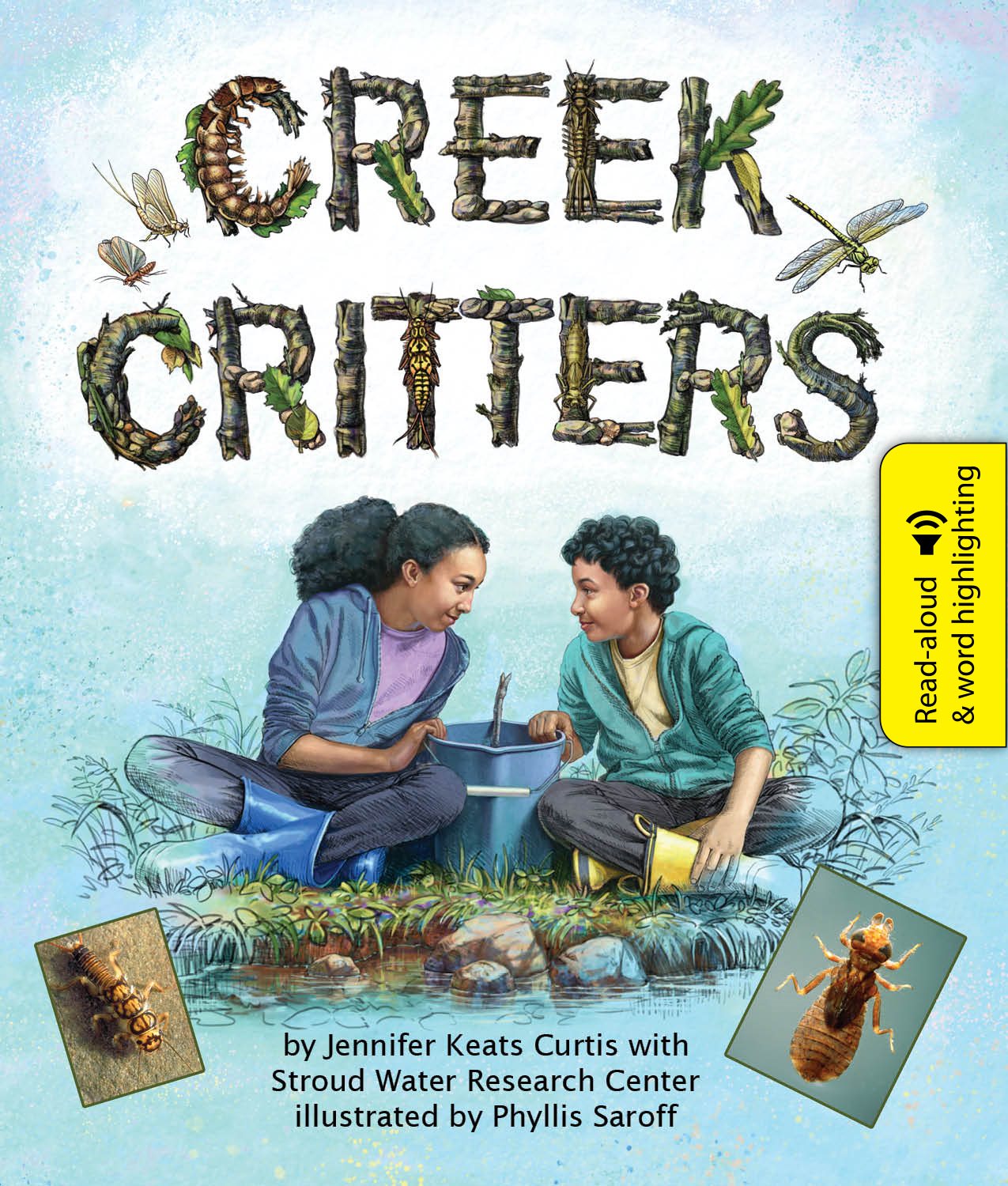

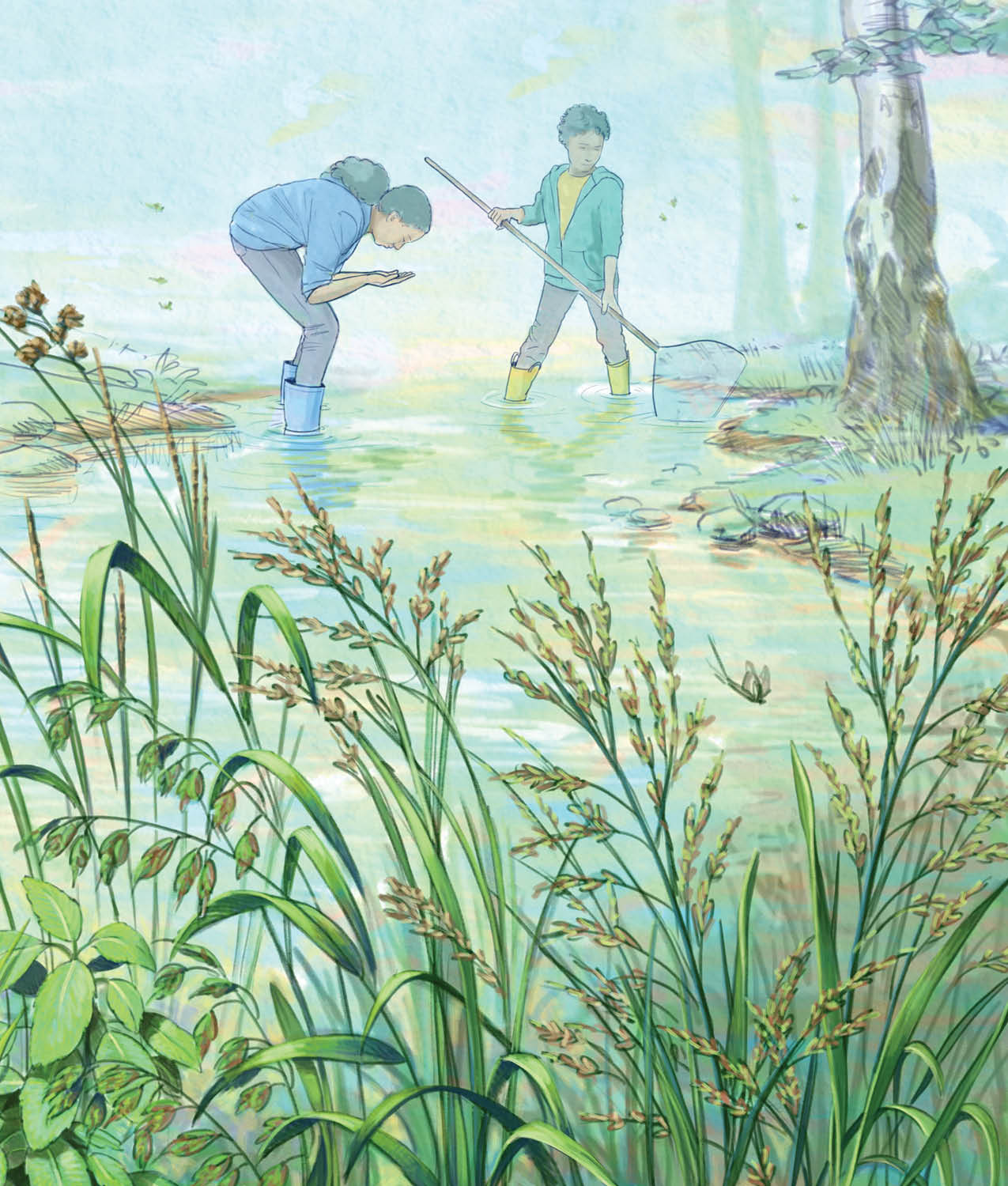

Like a team of scientists, we work together, searching for bugs that can only live in healthy water. Aquatic macroinvertebrates (or macros for short) is the fancy name for these creatures. If you break down the word, it's easy to understand. Aquatic means water. Macro means big; in this case, big enough to see with our eyes. No microscope needed. Invertebrate means no backbone. Young macros, called larvae or nymphs, live in water. As they grow older, some kinds of macros change-they go through metamorphosis. These adults fly around and live near the water, while other adults may spend their whole lives underwater.

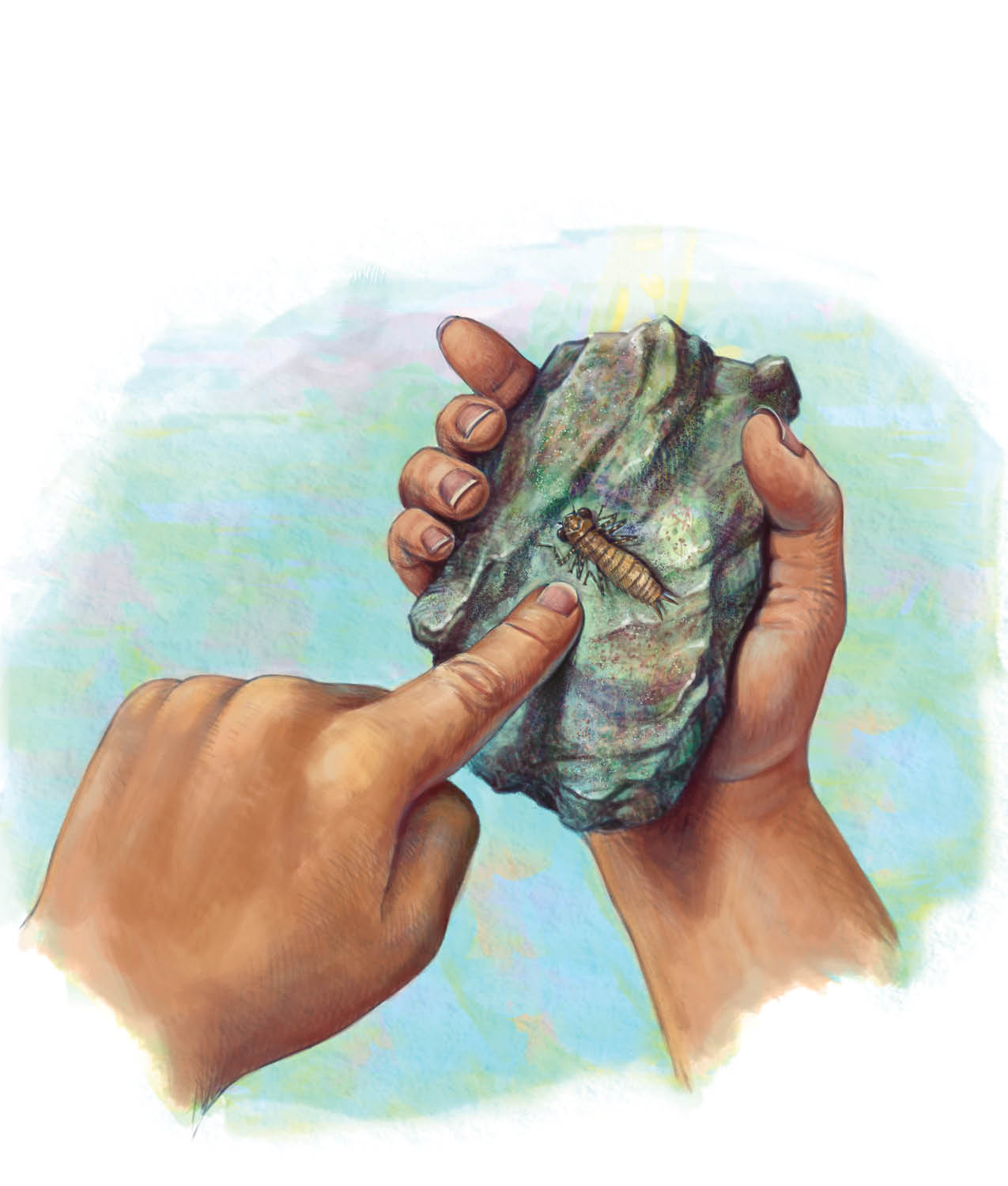

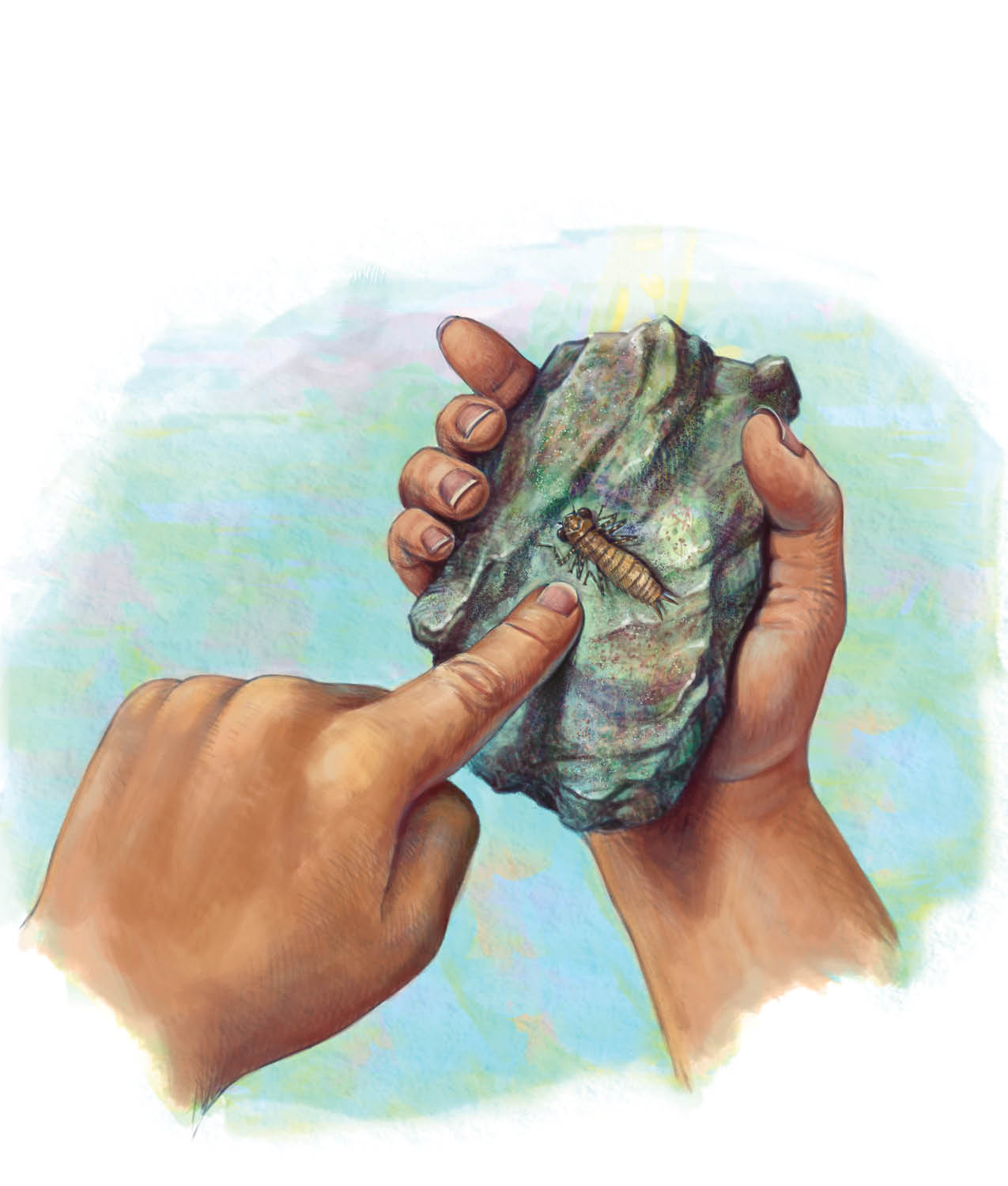

I yank up a rock. Lucas and I check the slimy bottom. Nothing. We wade over two steps. I snag a smaller grey stone for inspection. "There's some weird-looking crawler with big eyes on there," Lucas says very unscientifically.

I carefully scrape the bug into the bucket. He's a small but mighty dragonfly nymph! The young dragonfly spurts around as if he's wearing a jet pack. He sucks water in and spurts it out back, zooming from one side to the other. We put some sticks and leaves in the bucket so he can hide.

Lucas flips over another rock. I spy what looks like the smallest turtle I've ever seen. It's hanging on for dear life. It's actually a water penny, a beetle larva whose back looks like a turtle's shell. These beetles don't like creeks with pollution or muddy buildup (sediment). We put the water penny in the bucket.

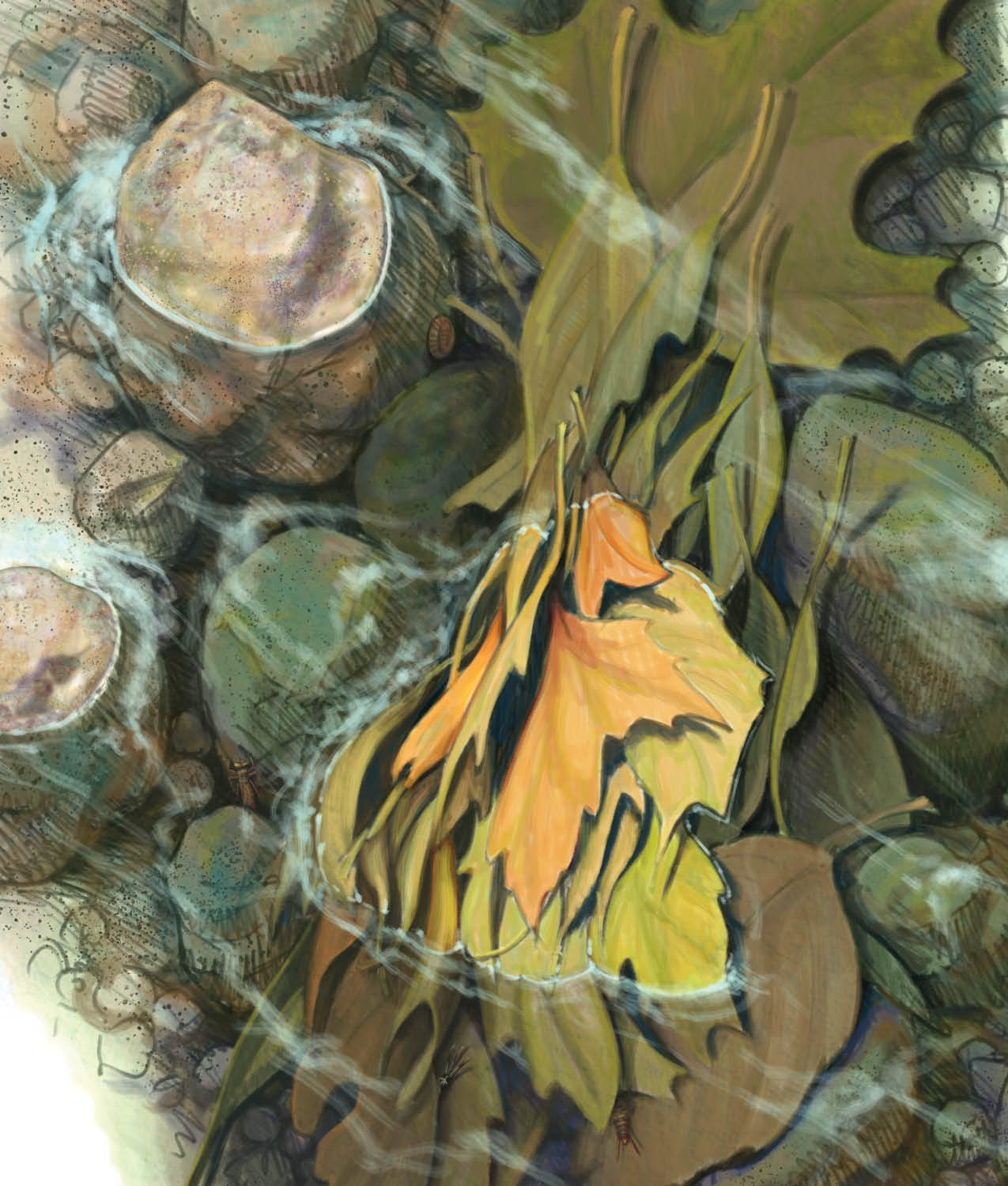

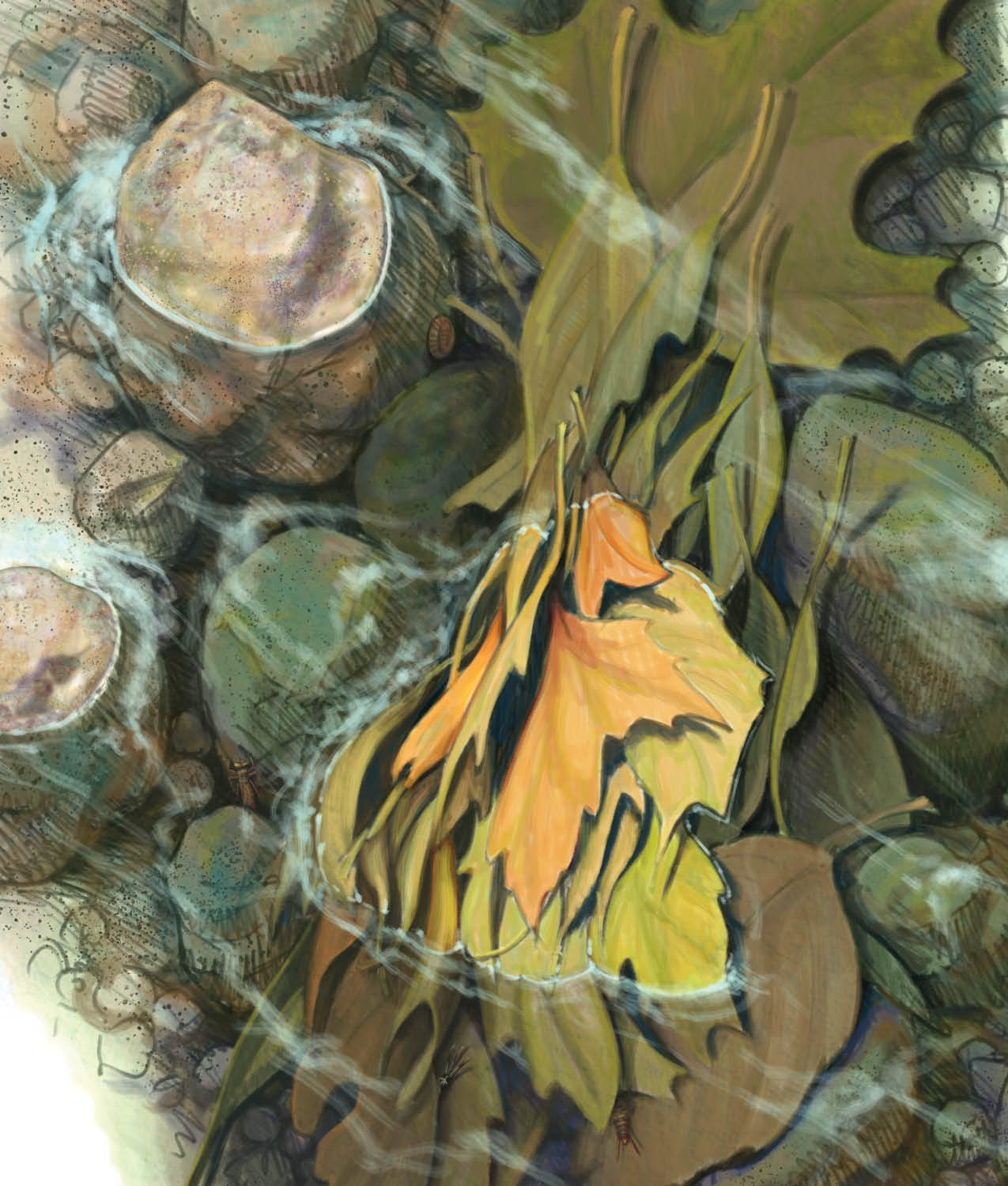

You can probably tell; these camouflaged creek critters are hard to spot. They can be as small as your eyelash or as big as your thumb. They hide, under, in, and around stones and pebbles. Some skitter into large bunches of leaves, called leaf packs. You can scoop up the pack with the net and slowly sift through it to check what's in there. We really want to find mayflies, stoneflies, and caddisflies. These bugs are the most sensitive to pollution. They often cannot live in dirty water. If we find them, we'll know our creek is healthy.

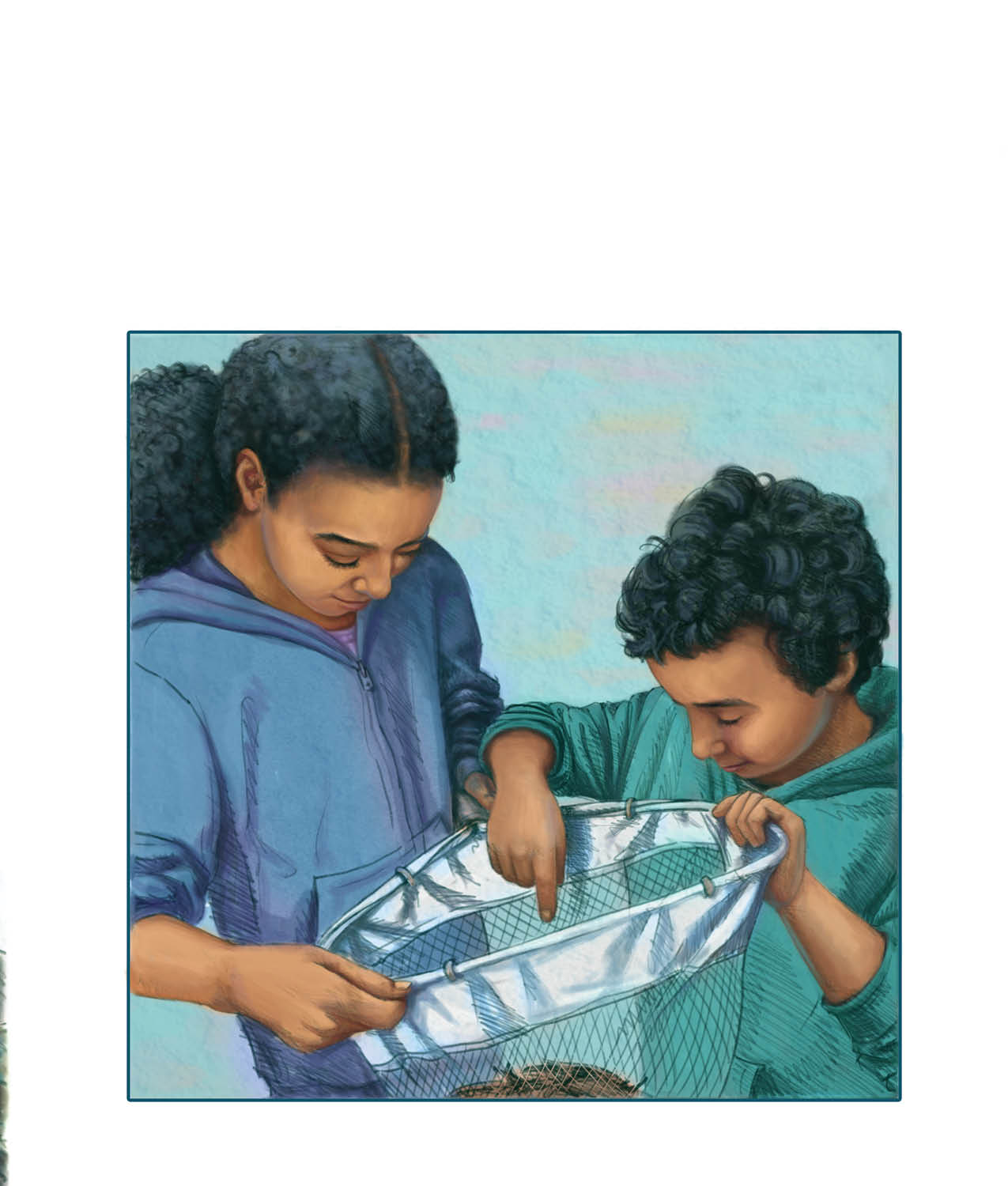

Lucas and I push the net underwater along the creek's edge. We shuffle our feet, kicking around so lots of stuff floats into our net. I pull up a hunk of rotting leaves, one of the best bug-hiding places. Of course, Lucas grabs a slimy leaf and flings it at me. Ugh, Lucas is always doing stuff like that. I wipe off the brown goo with a groan.

We quietly stare into the net. It's hard, but you have to be patient. The itty-bitty bugs are almost the same color as the leaves and are so small that you have to look for movement to find them.

There! A caddisfly larva pokes his head out of a homemade case of rocks, leaves, and twigs. This crafty critter creates his house using sticky silk as underwater glue. Lucas gently plunks him into the bucket. Before moving on, we examine the rest of the net to make sure there are no more bugs. They'll die if they dry out.

Now it's Lucas's turn to scoop with the net. We shuffle our feet again and a heap of grey, gooey, leaves glides in. As we pluck out the last leaf,