Introduction

If you ate today , thank a farmer

sign on a fence post, south of Perth, Ontario, July 2011

Kids take everything for granted. I was no different. Growing up on Torontos rural fringe, I explored the land and buildings of abandoned farms with more a sense of adventure than a sense of loss. Abandoned barns with buggies suspended from the rafters were more playgrounds than nostalgia to me then, but what I wouldnt give now to tuck my middle-aged brain into my boyhood skin to go back with a camera and a notebook and at least document what I saw in a respectful fashion.

This book then, must partly be regarded as an apology to the families who worked so hard to build their beautiful farms to feed us all; an apology from a boy on a bike who was more impressed by the bulldozers than what they were bulldozing. We can never go back. Life doesnt flow in that direction. We will never again see fields of grain at the corner of Leslie and Finch or hear the blacksmiths hammer ringing out across Hoggs Hollow, but we can take comfort in the stories and photos of the past, close our eyes and imagine a quieter time.

We can learn to appreciate the lives and accomplishments of these families whose names we may have only seen on street signs or historical plaques, and in so doing, offer our long overdue thanks.

Each chapter in this book describes either a specific farm or a specific family and follows their stories from the original Crown land grants near the dawn of the nineteenth century to the present day. It is my sincere wish that this book will give readers a new connection to present-day Willowdale and a new appreciation of those who have gone before. Its a lot easier to be stuck in traffic if you know whose farm you are on and can take the time to consider what they had to go through to make ends meet.

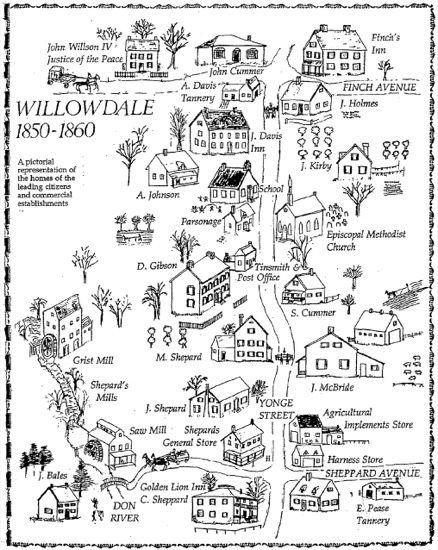

The name Willowdale has defined different areas through different eras. The origins of the name date back to 1855 when David Gibson successfully petitioned the government of Upper Canada for a post office to serve the area around his farm at Yonge Street and Park Home Avenue. He suggested the name Willow Dale, which was adopted. The area to the north, between Cummer and Steeles Avenues, was referred to as Newtonbrook at this time. In 1866, another post office opened to the south of Willow Dale at the intersection of Yonge Street and Sheppard Avenue. It was called Lansing, as was the community that grew up around it. As time went by, however, postal delivery was streamlined, and by the middle of the twentieth century the slightly renamed post office of Willowdale was serving the entire area from south of Sheppard to Steeles and from Bathurst Street to Leslie Street. The names Lansing and Newtonbrook continued in use on a localized basis as the whole area gradually came to be known as Willowdale. After the amalgamation of the six separate municipal governments in Metropolitan Toronto into the new City of Toronto in 1998, the post office address for the entire city officially came under the collective name of Toronto.

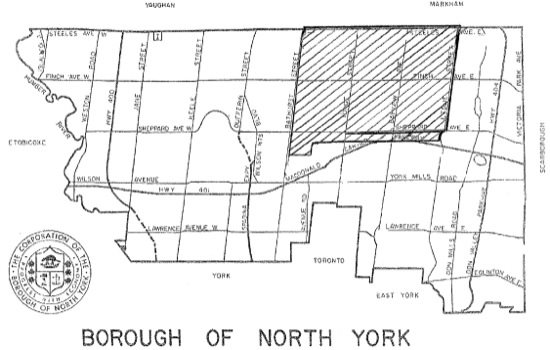

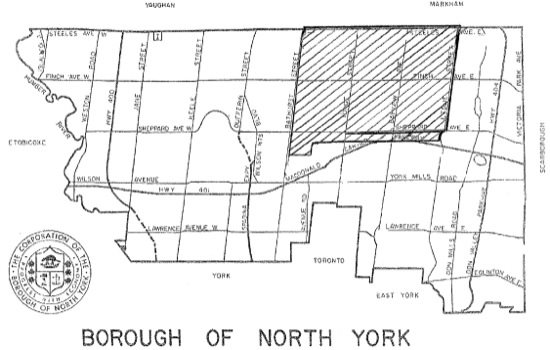

For the purpose of this book, Willowdale is defined as the area south of Steeles Avenue; north of Highway 401, west of Leslie Street, and east of Bathurst Street. Street names used in these stories are present-day names to allow for an easier visualization of the location of various farms.

Map of North York with Willowdale highlighted, adapted from the Borough of North York Historical Site Map, circa 1970.

Courtesy of North York Central Library.

{Background}

The Lives of the Early Settlers

and the Birth of North York

There are 44,442 acres in North York, enough for 222 full-sized two-hundred-acre farms. It was a great place for farms, with some of the most fertile land in the world, thanks to the deposits left behind by receding glaciers after the last ice age. The area had seen its fair share of nomadic, aboriginal activity for thousands of years before the first permanent settlements were established at the surprisingly late date of 1400 A.D. French priest and explorer tienne Brl was thought to be the first European to set foot in North York when he travelled down the Humber River, on his way from northern Ontario to Pennsylvania, in September 1615. For the next 170 years or so the only other Europeans would be fur traders and explorers passing through on their way to points north and west. It was not until the late 1700s that any thought was given to permanent white settlement in the area.

As Canadians, much of our time is spent wondering what our neighbours to the south are up to and back then a similar curiosity existed. Lieutenant Governor Simcoes arrival in 1791 was prompted by Great Britains desire to understand and maintain the land mass that would one day become Canada. The United States had already fought for and won its independence from the British who had no intention of losing all of North America.

John Graves Simcoe was appointed lieutenant governor of Upper Canada in 1791. He immediately had the jurisdiction, known then as the Home District, surveyed and divided into townships and ultimately nineteen separate counties to ensure that local issues would be addressed locally and not by some distant central government.

The Queens Rangers, which he had commanded during the American Revolution, accompanied Simcoe when he moved the capital of Upper Canada from Newark (Niagara-on-the-Lake) to York (Toronto) in 1792. Early in 1793 he began construction of Yonge Street from Lake Ontario north to the Holland River. This route, named after his friend, the British Secretary of War, Sir George Yonge, was critical to the future of Upper Canada in two ways. First, it was deemed the easiest trade route for reaching the north and west, but it also held great military significance. Hostilities between Great Britain and the United States were always bubbling just below the surface and Simcoe needed a back door to the Great Lakes. In the event that battles might erupt on Lake Erie or Lake Ontario, Simcoe wanted a route he could use to sneak up on the enemy from behind and take them by surprise. Yonge Street was central to his plans for preserving Upper Canada as a British colony.

With the West Don River being navigable as far north as Hoggs Hollow in those days, Simcoe decided that the best route to Georgian Bay and the Great Lakes was to use the Don River as far north as Hoggs Hollow, then portage his vessels by wheeled wagons all the way north to the Holland River. Once there they could once again be put in the water to head west to Georgian Bay and Lake Huron. Try to imagine the rigorous task of pulling lake bateaux out of the river in York Mills and then dragging them overland to Holland Landing. Such military moves would be unimaginable today.