Table of Contents

List of Figures

List of Tables

Copyright 2018 by Peter Lovie

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the author, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law.

Disclaimer:

The information and images provided have been

attributed as best as practically possible. Sources for content in

tables are identified where known. Best efforts have been used

to give a historical idea of what was done and sometimes

corrobrated with recollections of former colleagues.

ISBN-13: 978-1-945532-82-5

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018953493

Printed in the United States of America

Published, Edited, and Cover Design by:

Published, Edited, and Cover Design by:

Opportune Independent Publishing Co.

113 N. Live Oak Street

Houston, TX 77003

(832) 263-1700

www.opportunepublishing.com

Peter M Lovie PE, LLC

P.O. Box 19733 Houston TX 77224

Peter.Lovie@FPSOsinGoM.com

An email to discuss your ideas or point out any errors or typos would be welcomed.

If you enjoyed this book and felt others might like it, please consider writing a review on www.FPSOsinGoM.com , Amazon, or on the website you purchased your copy.

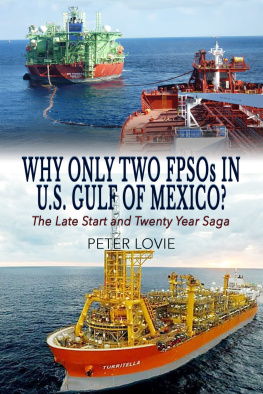

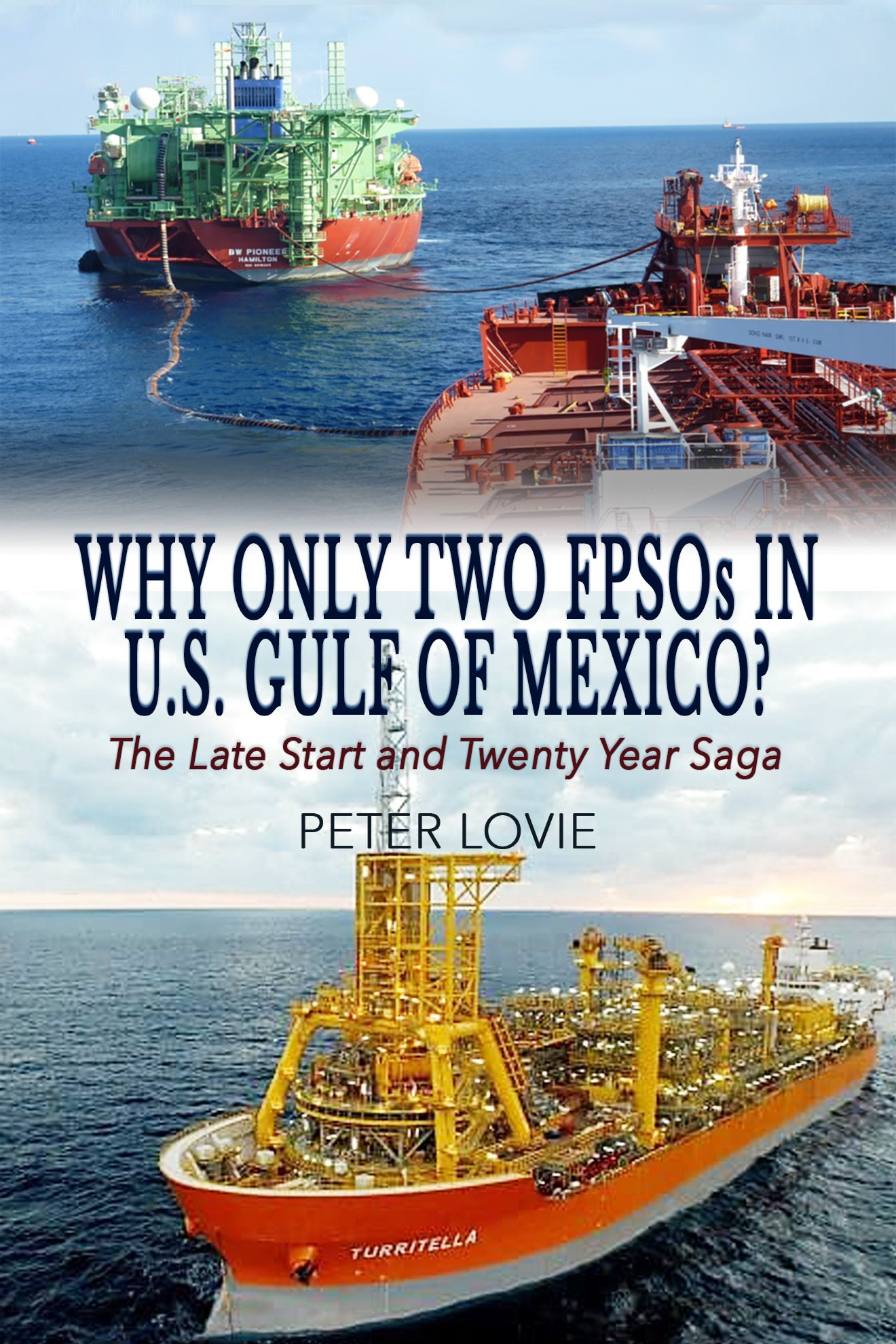

The upper image is of the FPSO BW Pioneer , owned by BW Offshore. It is the first FPSO in the U.S. Gulf of Mexico (US GoM) shown here while offloading to a shuttle tanker at the Petrobras operated Cascade/Chinook field development. First oil was 25 February 2012.

(Courtesy: BW Offshore)

The lower image is the second FPSO in US GoM: the SBM owned Turritella , shown on arrival at the Shell operated Stones development in US GoM in early 2016. Ownership has since been taken over by Shell.

(Courtesy: Shell)

Both FPSOs are discussed in the subsequent text, and the pictures repeated with more information.

Acknowledgements

The twenty-year saga for FPSOs in the GoM came about through the actions of thousands in the industry. The five individuals pictured here deserve particular recognition for their leadership: Allen Verret (Chevron, OOC, now retired), George Rodenbusch (Shell, now retired), Dave Bozeman (Devon, now retired), Cesar Palagi (Petrobras America) and Curtis Lohr (Shell, now retired). Their feedback has been invaluable in the preparation of this text.

For the historical background on the shuttle tanker business in Tables C and D, I am indebted to a former colleague: Alex Tischendorf, managing director for Teekay do Brasil Servicos Maritimos Ltda.

Preface

Introducing FPSOs into the U.S. Gulf of Mexico took much longer and was more difficult than anyone had imagined.

2016 saw the arrival of the second FPSO (floating production storage and offloading unit) in the U.S. Gulf of Mexico. Oil and gas industry experts recognized this as a major event because of the technical and business feats it accomplished. Although the U.S. Gulf of Mexico (GoM) has been a prominent pioneer for offshore oil and gas, FPSOs are the most used floating production system elsewhere and yet, the U.S. Gulf of Mexico has been curiously slow in adopting FPSOs.

The first FPSO arrived in 2010, but events beyond the control of the operating oil company led to first oil being delayed to February 2012.

This saga traces the events which made FPSOs in the GoM possible, starting in 1996 when GoM operating oil companies had already been producing offshore for fifty years. It tracks the steps from securing regulatory approval in principle, through the unexpected events which impacted the oil industry. It also explores the changes in design criteria and the decision-making process leading to the state of the industry in 2016, with one FPSO in operation and a second about to start production. Both employ unique Jones Act shuttle tankers.

Peter Lovie recounts frank anecdotes from the middle of it all. His unusual succession of Houston-based careers with an FPSO contractor, a shuttle tanker contractor, an operating oil company, and (currently) an independent consulting company give him an insiders insight on these events and a compelling outlook for future FPSOs in the GoM.

How Did It All Start?

It was not until fifty years after World War II that the idea of FPSOs in the U.S. GoM started to gain traction. Although the U.S. had started offshore production (most dramatically in 1947 with Kerr McGees first platform out of sight of land), there had been only one U.S. FPSO precedent during that fifty-year period: an operation where Exxons OS&T was moored in 490 ft. of water at their Hondo development offshore Santa Barbara, California. From 1981-1994, the location employed a 50,000 DWT tanker for production, with export by tanker. By comparison, elsewhere in the world, offshore Spain Shells Castellon FPSO started operation in 1977, and on the Mexican side of the Gulf of Mexico, there had been occasional experiments with FPSOs since 1989.

It was not until 1995-1996 that Texacos Fuji prospect drew attention to the possible use of an FPSO in the GoM with an unusual requirement in 1,700 feet of water deep water in these days and at a relatively remote location from pipelines. Back then, the leading regulatory authorities were the Minerals Management Service (MMS), concerned with safe petroleum production, and the United States Coast Guard (USCG), concerned with issues of vessel safety and operation. These realms were particularly relevant to FPSOs, which float, store, and offload oil.

In late 2001, the MMS Record of Decision stated that: In 1996, Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) operators, as well as builders and operators of FPSO vessels, began having serious discussions with the MMS about the possibility of using FPSO systems in the Gulf of Mexico.

Operators in the U.S. GoM took the initiative to open discussions with the MMS. These talks revealed that MMS would require an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) before they would consider any application to use an FPSO for any specific field development in the U.S. GoM. An EIS had not been required for earlier facilities in deep water such as jackets, guyed towers, tension-leg platforms (TLPs), spars, and semisubmersible production platforms; however, apparently what made all the difference was the FPSOs novelty, its storage of oil on the production facility, and its transport to shore by tanker instead of by pipeline. The Valdez oil spill had occurred just a few years earlier in 1989, and there was serious public concern over the potential of future spills.

Further, MMS did not see why they should undertake the effort of adopting FPSOs at their cost.

Preparation of an EIS meant a serious delay of at least two years. To any operator with the philosophy time is money, it posed an excruciating obstacle to developing newly discovered reserves. This move eliminated the option of FPSOs from practical consideration. Other operators besides Texaco also wanted to have FPSOs in their toolbox for immediate action in future developments without the EIS delay.

Published, Edited, and Cover Design by:

Published, Edited, and Cover Design by: