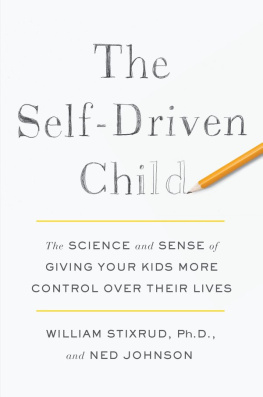

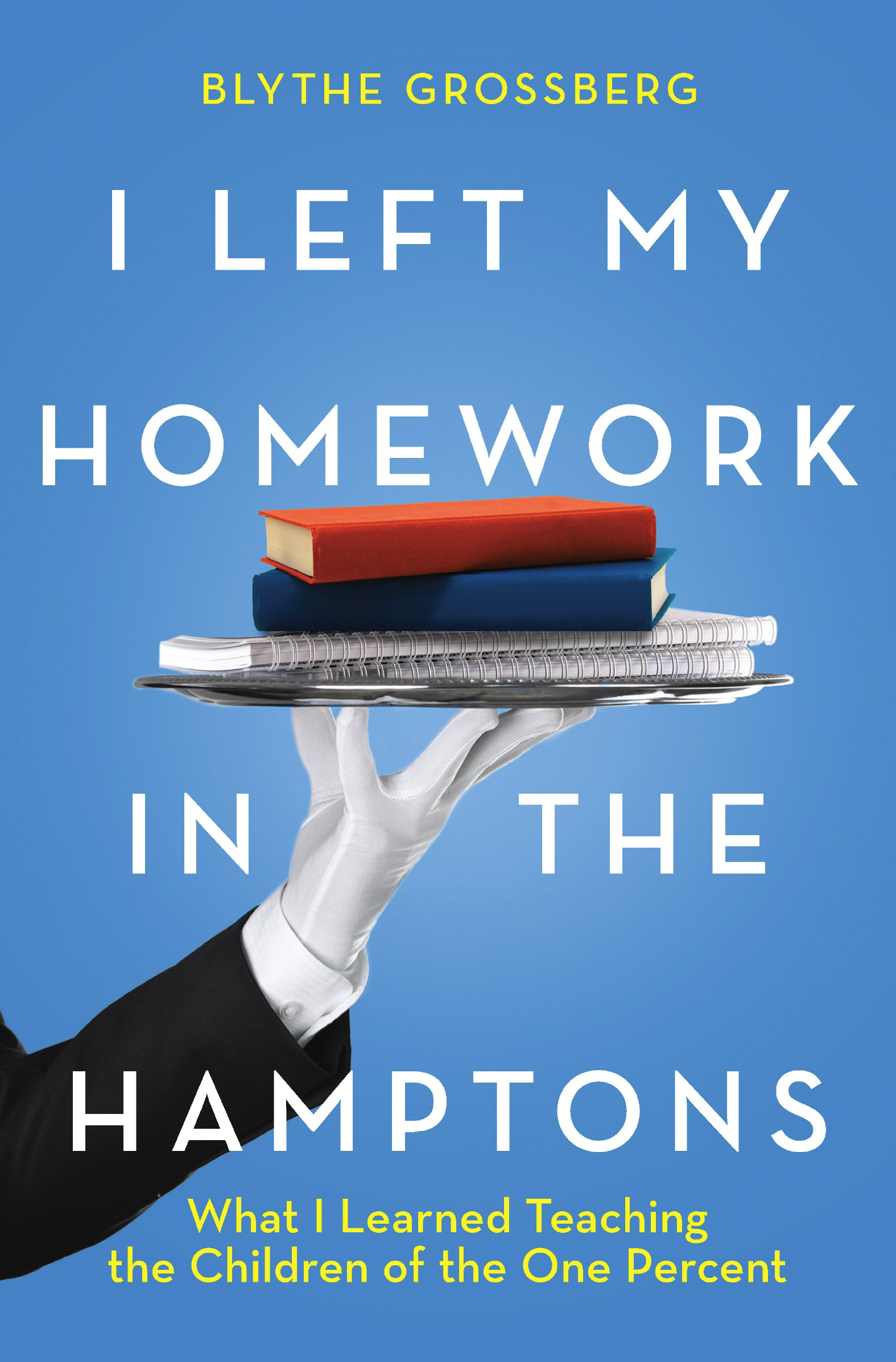

I Left My Homework in the Hamptons

Blythe Grossberg

What I Learned Teaching the Children of the One Percent

For J.D. and T.D.

Table of Contents

Authors Note

A note about the characters in this book: The characters are based on the nearly twenty years I spent working with thousands of students in New York City. I have changed the names and identifying details and created composite characters to protect the identities and privacy of the people in the book. This book has elements of memoir, which reflect the authors present recollections of experiences in the past. Some events have been compressed, and some dialogue has been re-created. I tried to represent with accuracy the world I portray. Human memory is not perfect, but my intent was always to render the characters, particularly the children at the heart of the book, with fidelity and humanity.

1

The Doors of Fifth Avenue Open

When I meet my first tutee, fifteen-year-old Sophie, she sweeps down a grand, winding staircase covered with white carpet. Her Park Avenue duplex is appointed entirely in white, from the couches to the shag carpet to the miniature poodles yapping at her feet. The short skirt of her private-school uniform flaps as she scoops up one of her dogs, orders it to be quiet, and tweaks the bow on its tiny head. Before we ascend to work on writing, her housekeepers, two Filipino women, ask us if we would like anything to eat or drink.

In her room, a pink gingham bedspread matches the fabric on her desk chair. Everything else is white and spotless. The usual mess of a teenagers room is nowhere in sight. She has neatly stacked up her school books, but they are the only sign of clutter. Even her flat-screen TV is stored behind a wood console, and the only objects disturbing the whiteness and pinkness of her space is her collection of Limoges boxes, carefully arranged at right angles to each other. There is a photo in a crystal picture frame of her with her dad taken at a golf tournament in the Hamptons. It is only when she opens the built-in cabinets over her desk that I see the magazine cutouts that clutter most teenagers rooms alongside photos of her friends wearing too much makeup, dressed to the nines in designer dresses and high heels.

After getting out her copy of The Great Gatsby , she begins to speak about her assignment: to write an expository essay about whether Gatsby achieved the American dream. Her two white dogs start barking again until one of the Filipino women comes to hush them and haul them downstairs.

Im going to say that Gatsby did not achieve the dream, she says, because thats what my teacher thinks. She pauses for a minute and licks her lips nervously. Unless you think I should write something else.

We go back and forth talking about the ideas, and I can sense that shes nervous that I think theres no one right answer. Instead, I ask her to find support in the text for her contention that Gatsby failed to achieve the dream. She leafs through the pages mechanically, her nails painted with glittering polish that she has half picked off. She reads the following passage about Gatsbys riotous, lavish parties:

Every Friday five crates of oranges and lemons arrived from a fruiterer in New Yorkevery Monday these same oranges and lemons left his back door in a pyramid of pulpless halves.

She is ready to skip ahead, until I ask her to slow down and think about this image. My parents kitchen looks like that during a party, too, she says. All those lemon rinds next to the bar. And my mom almost looks like a wrung-out lemon after a long night. She realizes that partygoers have trampled Gatsbys house, just as they regularly trash her parents Hamptons house in the summer, and that the result is a sense of lethargy and letdown. The passage seems to make sense to her and to connect to her personal experience.

She uses the intercom on the wall next to her desk to buzz her maids to bring up some green tea, which appears in a matter of minutes in porcelain cups and saucers with thin lemon wedges teetering on the rims. We eventually hammer out an outline, and I think she has done a good job coming up with an arguable thesis and marshaling some evidence from the text. She musters a faint smile as I leave.

Or did Gatsby achieve the dream? she wonders aloud.

I leave elated. This has been a heady experiencethe green tea, the white dogs, and getting paid to talk about Gatsby. I never dreamed that all my years of reading and being made fun of for loving poetry in public high school would actually result in something lucrative and fulfilling.

My route to Sophies house was a circuitous one. While earning my doctoral degree in psychology, I had two major problems. The easier of the two was rejecting Freudianism in favor of behavioral approaches after I deemed Freud out of touch with modern realities. The harder one was being able to afford new shoes, instead of walking with holes in both of my flats, or an iced coffee for the homeless man who lived in the lobby of my building in Park Slope, Brooklyn. Or even buy one for myself, for that matter. It was also hard to afford subway fare, hence the walking, hence the holes in my shoes. I had essentially discovered that while my Harvard undergraduate education had made me very well-read, it did not automatically earn me subway fare. That was my fault, though, as I had bypassed lucrative financial jobs to study psychology, while my husband, also an Ivy grad, had become a magazine editor. We had a lot of books packed into our shabby apartment. Still, I believed that psychology would unravel the mysteries of the human mind, everything from altruism to irrationality, and just peeking into these mysteries was worth more to me than a six-or seven-figure income.

I thought a great deal while treading the streets of New York in my worn-down soles, and I was fortunate enough to strike upon the idea of writing a dissertation about ADHD that helped pave my way to working with students with learning differences and ADHD. When I got a job as a learning specialist, a teacher who helps students with such learning differences, in an elite Manhattan private school at an annual salary of $54,500, I felt secure for the first time in a long time, even with a newborn to care for at home. After years of earning a subsistence income, I decided I needed something steadier now that I had a young one of my own. I had lived in New York for ten years, and I so far had been able to scrape by without dipping into the gig economy. But when my friend who taught at an Upper East Side girls school asked if Id help a sweet, stressed-out sophomore with writing, I was ecstatic. This was the kind of work Id do for free. The idea of getting paid for itand on top of my salarywas nirvana, almost unthinkable. Back in rural Massachusetts where I grew up, kids used to cheat off me for nothing.

To enter the calm, secure, sedate Park Avenue lobby of the building where this girl lived was to enter a world that promised the freedom of the rich, the transcendence of an art museum, and the satisfaction of calming a nervous fifteen-year-old. Little did I know that Freud, whom Id so casually rejected in graduate school, was lurking, waiting for me in the hushed, lily-filled interior of those Park Avenue buildings, where neuroses of all sorts waited.

After Sophie earns her first A on a paper, rocketing up magically from her usual B+, I become a bit of a hot commodity in the duplexes and brownstones of Brooklyn and Manhattan. I am like the restaurant that is so trendy it isnt even in Zagats yet. Later, after Ive found some more students to tutor, mothers refer to me as their secret , and one is upset that her daughters rivals mother has found out about me, too. But we discovered you, she wails.

Next page