Jesse Wente - Unreconciled: Family, Truth, and Indigenous Resistance

Here you can read online Jesse Wente - Unreconciled: Family, Truth, and Indigenous Resistance full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, publisher: Penguin Canada, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

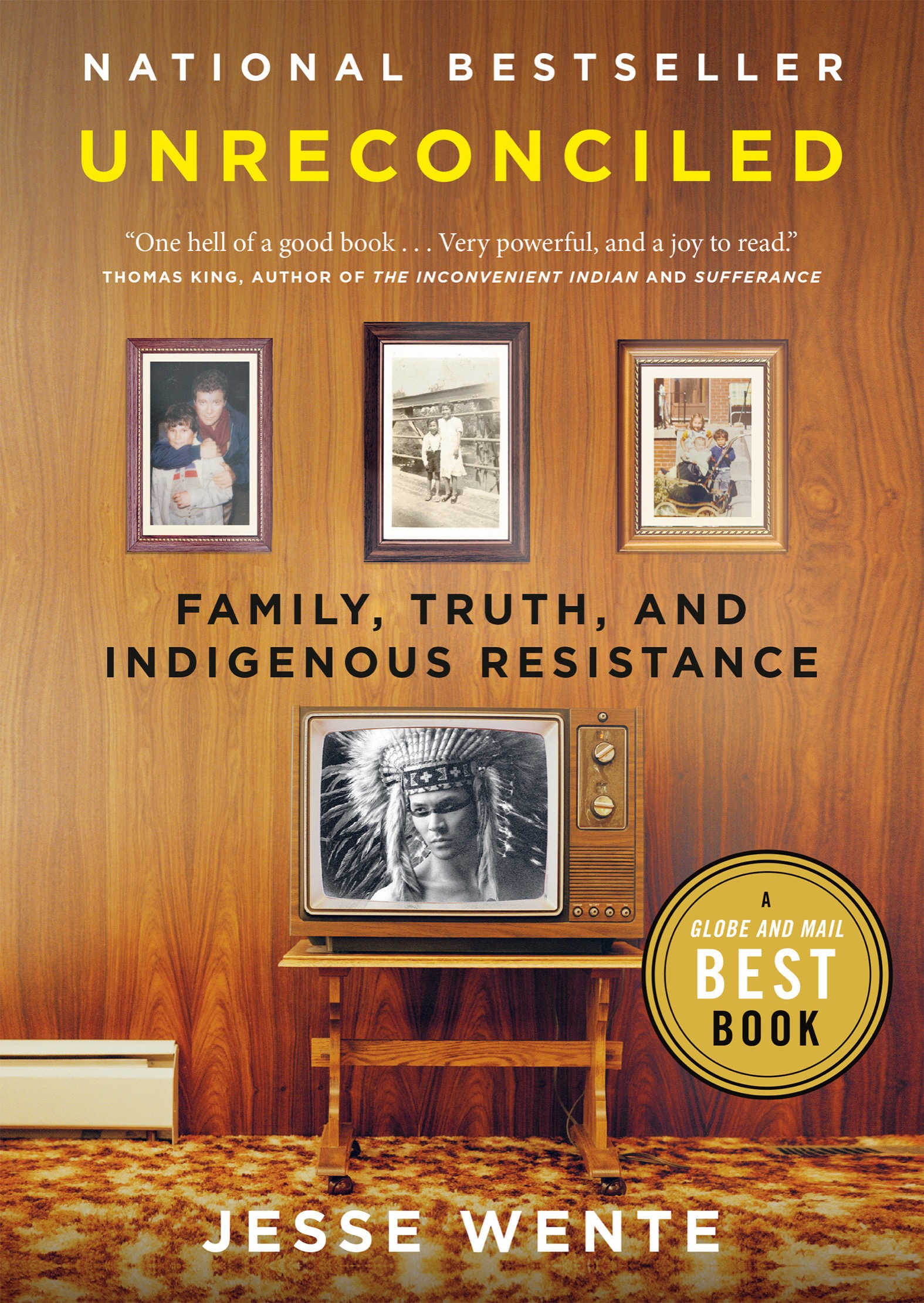

- Book:Unreconciled: Family, Truth, and Indigenous Resistance

- Author:

- Publisher:Penguin Canada

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

Unreconciled: Family, Truth, and Indigenous Resistance: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Unreconciled: Family, Truth, and Indigenous Resistance" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

WINNER of the 2022 Rakuten Kobo Emerging Writer Prize for Non-Fiction

A GLOBE AND MAIL BEST BOOK OF THE YEAR

Unreconciled is one hell of a good book. Jesse Wentes narrative moves effortlessly from the personal to the historical to the contemporary. Very powerful, and a joy to read.

Thomas King, author of The Inconvenient Indian and Sufferance

A prominent Indigenous voice uncovers the lies and myths that affect relations between white and Indigenous peoples and the power of narrative to emphasize truth over comfort.

Part memoir and part manifesto, Unreconciled is a stirring call to arms to put truth over the flawed concept of reconciliation, and to build a new, respectful relationship between the nation of Canada and Indigenous peoples.

Jesse Wente remembers the exact moment he realized that he was a certain kind of Indiana stereotypical cartoon Indian. He was playing softball as a child when the opposing team began to war-whoop when he was at bat. It was just one of many incidents that formed Wentes understanding of what it means to be a modern Indigenous person in a society still overwhelmingly colonial in its attitudes and institutions.

As the child of an American father and an Anishinaabe mother, Wente grew up in Toronto with frequent visits to the reserve where his maternal relations lived. By exploring his familys history, including his grandmothers experience in residential school, and citing his own frequent incidents of racial profiling by police whod stop him on the streets, Wente unpacks the discrepancies between his personal identity and how non-Indigenous people view him.

Wente analyzes and gives voice to the differences between Hollywood portrayals of Indigenous peoples and lived culture. Through the lens of art, pop culture, and personal stories, and with disarming humour, he links his love of baseball and movies to such issues as cultural appropriation, Indigenous representation and identity, and Indigenous narrative sovereignty. Indeed, he argues that storytelling in all its forms is one of Indigenous peoples best weapons in the fight to reclaim their rightful place.

Wente explores and exposes the lies that Canada tells itself, unravels the two founding nations myth, and insists that the notion of reconciliation is not a realistic path forward. Peace between First Nations and the state of Canada cant be recovered through reconciliationbecause no such relationship ever existed.

Jesse Wente: author's other books

Who wrote Unreconciled: Family, Truth, and Indigenous Resistance? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.