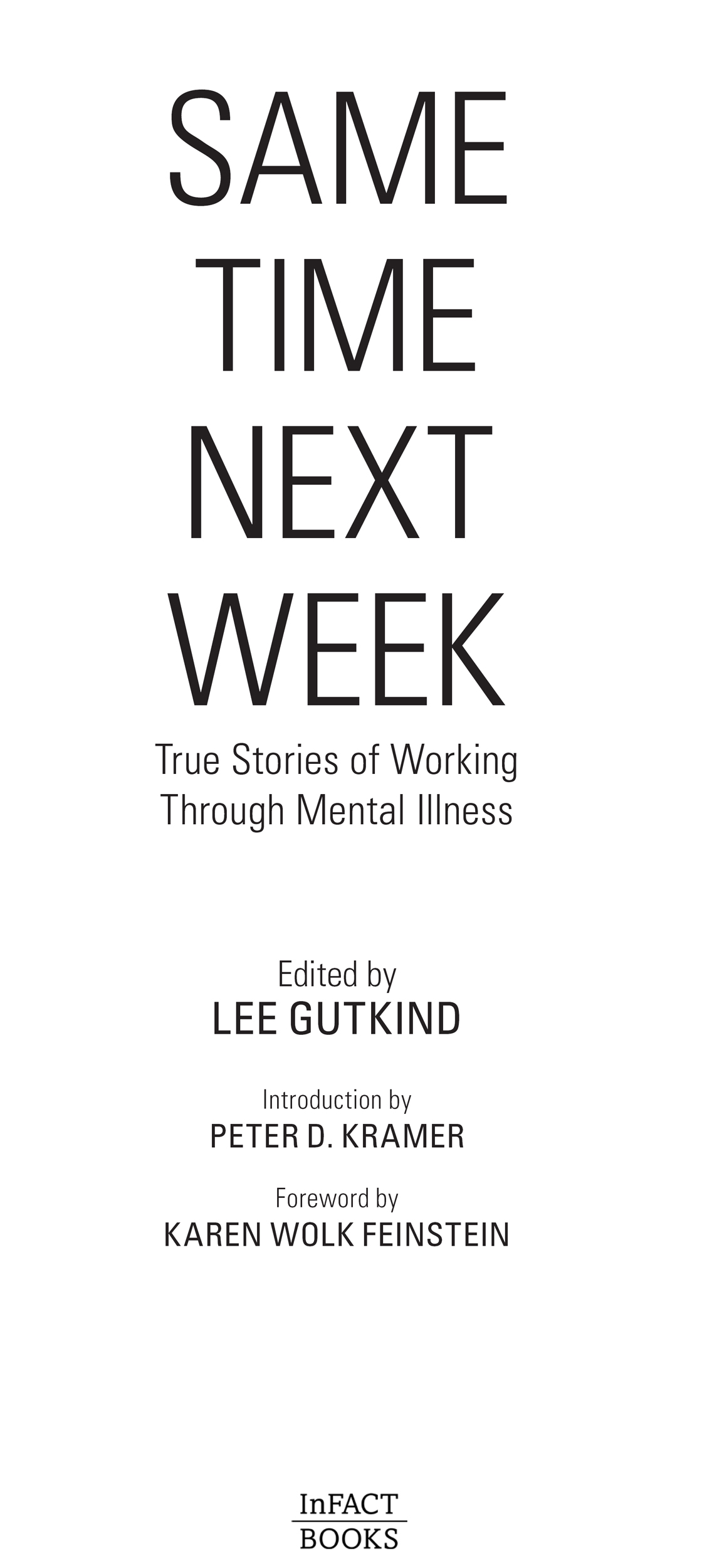

Copyright 2015 Creative Nonfiction Foundation.

All rights reserved.

Tom Mallouks Im Not a Noun Either is excerpted and adapted from Reflections on Psychiatry, the Fear of Insanity, Trauma and Psychotherapy, originally published in the Spring 2014 issue of Solstice, and appears here by permission of the author.

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to:

Rights and Permissions

In Fact Books

c/o Creative Nonfiction Foundation

5501 Walnut Street, Suite 202

Pittsburgh, PA 15232

Cover and text design by Heidi Roux

ISBN: 978-1-937163-20-4

CONTENTS

Peter D. Kramer

D isorders of mind and brain can be powerful. Something goes wrong. The glitch or, worse, major disturbance may involve reasoning, perception, feeling, energy, relationship patterns, personality traits, or repeated behaviors. The problems rarely remain delimited. They can claim much of a life, unless a solution emerges. Sometimes, after years of slippageintrusive thoughts, destructive impulses, paralyzing mood states, relentless addiction, intractable paina person finds a footing. But how? What works when nothing has worked?

These memoirists, whether healers or sufferers, are mostly in agreement: relief comes from outside the mainstream of care. Its not that there are no good guys; in What Would My Mother Say? Annita Sawyeronce suicidal and hallucinatingwrites of a psychiatrist whose steady centeredness, flexibility, and sense of humor got through to me. But Sawyers story is also one of institutional failure: over-aggressive treatment, grounded in a failure to explore, to listen, to elicit the crucial elements of history and experience.

Most often in these stories of recovery, the source of change is idiosyncratic, unexpected, a step or two off the common path. Standard-issue treatments garner scant respect. Cognitive behavioral therapy, the current darling of the professions, is no favorite. Its the existential approachpersonal presence, radical acceptancethat does the job, if the job can be done through psychotherapy.

Unconventional moves in psychotherapy receive the occasional nodholding, walking, digging a hole to bury misery and shame. Generally, the cure is partial. Thats fine, too. The first goal, when people are drowning, is to get them afloat. Reaching shore comes later.

Medication earns mixed reviews. Ronald Bassman, a patient turned psychotherapist, finds them overused: Research has shown that these drugs do physical damage and inhibit recovery. J. Timothy Damiani, a psychiatrist, works a one-off transformation with lithium, a drug thats on my own short list of favorites.

And what if, as is mostly the rule here, mainstream effortstalk therapy and drugsare not enough? We learn about religious retreat, reading, speech therapy, self-advocacy, and the kindness of relatives, friends, and fellow patients. For Candy Schulmans brother-in-law, Will, laid low by an especially debilitating form of schizophrenia, the miracle arrives mostly on its own, spontaneous remission nudged along, perhaps, by modest help from medication.

One villain in these tales is diagnosis. Patients accumulate labels, with little clarity gained. Some of these labels are mistaken; more are unhelpful. Reading Sharron Hoys account of her long-term misdiagnosis, I was reminded of a lecture by my colleague George Vaillant, titled The Beginning of Wisdom Is Never Calling a Patient a Borderline. Certain categories lead us, doctors and patients both, deeper into the thicket.

As a practicing psychiatrist, I worry, if slightly, that this collection obscures the reliable help available from routine care. What with scandals concerning doctors and drug companies and controversy concerning diagnosis and the role of placebo effects, the media sometimes convey the impression that the mental health professions have little to offer.

In practice, most patients who seek treatment respond to it. To cite a snippet of data from the field I know most about, mood disorders, a well-conducted Swedish study found that when primary care doctors offered moderately depressed patients standard medication, 90 percent of those who followed through experienced substantial improvement. Why is a different matterperhaps the white coat did the job; perhaps (I hold this view) antidepressants are reasonably effective. The point is that typical patients with common ailments generally do well.

Diagnosis, too, can be decisive. Psychiatry and psychology have specific approaches, pharmacologic and psychotherapeutic, for obsessive-compulsive disorder, bipolar disorder, and others. And then there is the boundary with general medicine. Epilepsy, anemia, hormone or vitamin deficiencies, side effects of prescribed drugsthe list of categories for which specific remedies exist is a long one. Often, fixing or mitigating the underlying condition relieves the mental symptoms decisively.

Still, the professions failures are legion. Physicians, psychologists, nurses, social workers, and psychotherapists of many stripeswe all work with non-responders, with people who suffer what is sometimes called the career of depression, the career of anorexia, the career of schizophrenia, and on and on. Chronicity and recurrence are the norm. These stories come from that territory, bleak and fascinating. What is the route across, the passage through, the fruitful journey? Confidence and curiosity on the part of caregivers make a difference. So do compassion and persistence on the part of coworkers and employers, ministers and fellow sufferers, friends and relations. But those answers, true in their way, are too pat. These detailed personal accounts point to the limit of our art and science. When they no longer avail, we are fully in the realm of what used also to be called the existential: where terror prevails, where stubbornness and belated good luck become critical, where the individual, hand-crafted solution is the only one we can hope to find.

Peter D. Kramer is a psychiatrist and author, and currently a clinical professor of psychiatry and human behavior at Brown University. His books include Listening to Prozac and Against Depression.

Lee Gutkind

I n some ways, the subtitle of this bookWorking Through Mental Illnessdoesnt quite capture the challenge, struggle, and triumph of these remarkable true stories. Theres morea reality Peter Kramer captures in his incisive and thought-provoking introduction when he refers to the inadequate and sometimes harmful treatment of those who suffer from mental illness and to an institutional failure which, I believe, is at the heart of the problem.

I have been writing about the world of mental health for most of my career, focusing primarily on this institutional failurethe dysfunctional system that inadequately supports and often significantly harms patients and their families and, indirectly, our entire country. The statistics are staggering and sobering. According to the National Institute of Mental Health, one in four adults (approximately 61.5 million Americans) and one in five young persons (ages 1318) experiences a diagnosable mental disorder in a given year. Even more staggering, 60 percent of those adults and half of those adolescents and young adults will not receive treatment over a years period. Besides being morally indefensible, this is practically unsustainable. Serious mental illness costs America nearly $200 billion in lost earnings every year. And the societal stigma attached to those who have suffered from mental illness makes recovery and reintegration into societyand the workforcechallenging and sometimes impossible.

Next page