Preface

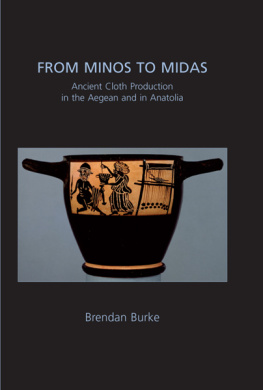

My mother liked to weave and sew, so I grew up with interesting textiles all around, learning to sew and weave for myself at an early age. I was constantly being made aware of the form, color, and texture of cloth. Textiles have a particular crossing structure that dictates what sorts of patterns will be easy and obvious to weave or, conversely, hard to weave. Thus later, when I began to study Classical and Bronze Age Mediterranean archaeology at college, I soon noticed decorations on durable things like pottery and walls that looked as if they had been copied from typical weaving patterns. But when I suggested this idea to archaeologists, they responded that nobody could have known how to weave such complicated textiles so early. The answer was hard to refute, on the face of it, because very few textiles have come down to us from before medieval times, outside of Egypt, where people generally wore plain white linen.

Unconvinced, I decided to spend two weeks hunting for data on the degree of sophistication of the weaving technology, to see at least whether people could have made ornate textiles back then. I expected to write my findings into a small article, maybe ten pages, suggesting that scholars ought to consider at least the possibility of early textile industries.

-11-

But when I began to look, data for ancient textiles lay everywhere, waiting to be picked up. By the end of the two weeks I realized that it would take me at least a summer or two to chase down and organize the leads I had turned up and that I could be writing a 60-page monograph. By the end of two more summers I knew I was headed for a 200-page book. That "little book" turned into a research project that consumed seventeen years and yielded a 450-page tome covering many times the planned geographical area and time span. It finally appeared in 1991 as Prehistoric Textiles, from Princeton University Press.

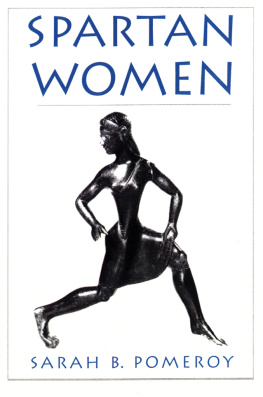

For that book I had restricted myself to the history and development of the craft: a big enough topic, as it turned out. Along the way I kept running across wonderful bits of information about the womenvirtually always womenwho produced these textiles and about the values that different societies put on the products and their makers. When I talked about my work, people seemed especially eager for these vignettes, stories that told of women's lives thousands of years ago. They urged me to write a second book on the economic and social history of ancient textiles, in effect on the women who made the cloth and clothing.

Then a friend asked me to read her unfinished translation of the memoirs of Nadezhda Durova, a woman who had spent ten years disguised as a man serving in the czar's cavalry during the Napoleonic Wars. Far from giving a catalog of campaigns, battle arrays, and tactics, Durova spent the entire war recording how people lived from day to day: how she and her fellow soldiers interacted with horses, geese, each other, the weather, and the local folk with whom they were billeted. I am not normally fond of reading history, but this was different. I could hardly wait for each new installment. As I realized that the source of my fascination was the glimpses into real people's lives, I began to understand in a new way what my early material contained. (This book has now appeared as The Cavalry Maiden, translated by Mary Fleming Zirin [Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988].)

Thus I have tried to explore and pull together what real facts

-12-

we can deduce about early women, their lives, their work, and their values, chiefly from the technological record of the one major product of women that has been well studied as yettextiles. I have also paid some attention to what language can tell us. Messages perish as they are uttered, but language itself is remarkably durable. Sometimes it preserves useful clues to a more abstract and thought-oriented part of the human past than material artifacts do.

Perhaps the most important thing that has been omitted from this book, however, is fiction. Romantics may enjoy Hollywood tales of Ooga and Oona grunting around the fire of a squat and hairy, stoop-shouldered Palaeolithic ruffian, after he has dragged them in by the hair from the next cave. Idealists may savor the rosy utopian visions of "life before war" in a Neolithic age ruled by women totally connected to the pulse of Mother Earth. These stories are fun. But what, I ask, was life really like? What hard evidence do we have for what we might want to know about women's lives? No evidence means no real knowledge.

Stacked against our endless questions, what we know remains small, and no matter how clever we become at tracking down evidence, if we want reality, we are stuck with what fragmentary facts we happen to have. I have not invented answers just to fill in, the way a screenwriter must. But we know much more than has gotten into the general literature about women's history. The reader will find in these pages glimpses of real women of all sortspeasants, entrepreneurs, queens, slaves, honest souls, and crooksgood and bad, high and low. For all the strangeness of their cultures, they seem refreshingly like us.

-13-

[This page intentionally left blank.] |

|