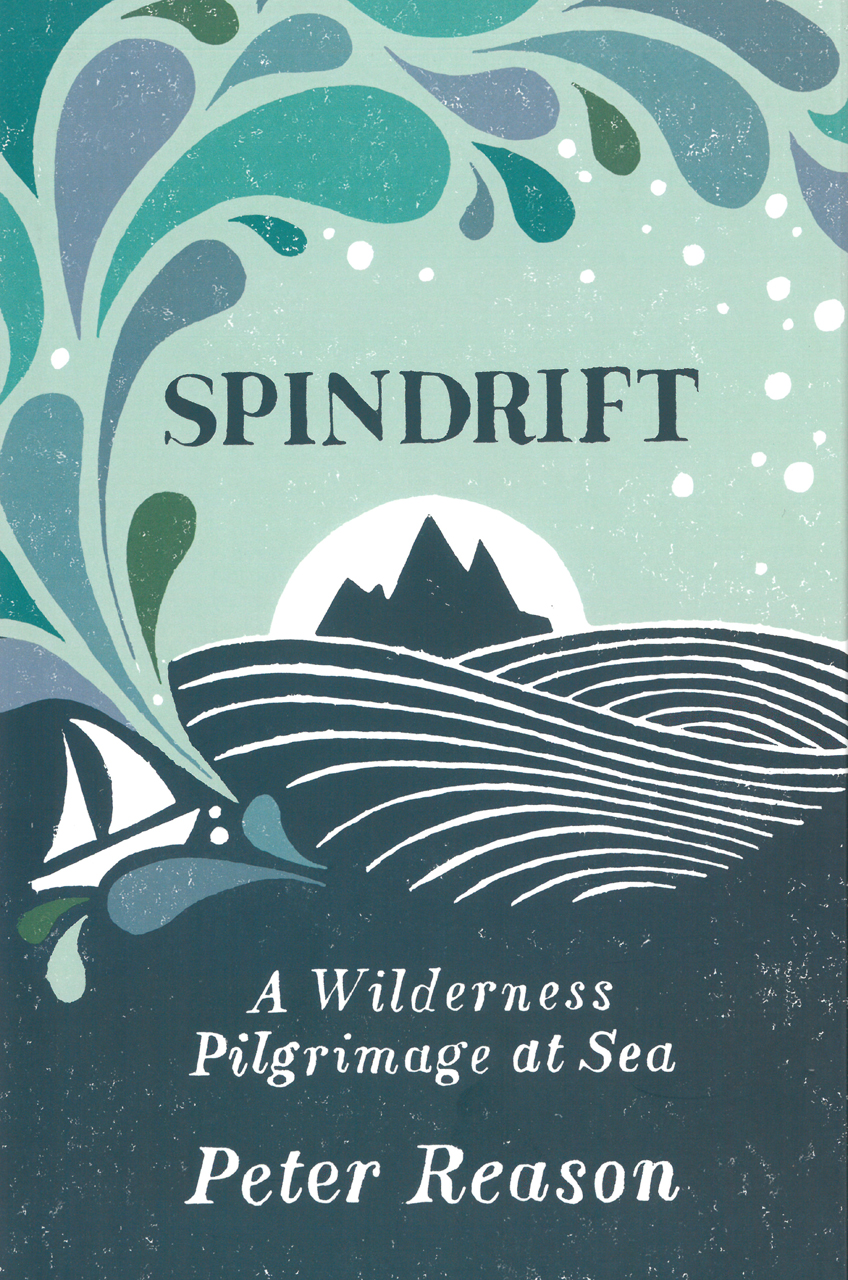

Spindrift is the spray blown off the crests of

waves in winds of gale force and above. For sailors

in a small boat, spindrift is the sign that forceful

but workable conditions are becoming dangerous.

Spindrift

A Wilderness Pilgrimage at Sea

Peter Reason

Jessica Kingsley Publishers

London and Philadelphia

Excerpt from Lao Tzu, Tao Te Ching: A New English Version , by Ursula K. Le Guin.

Copyright 1997 by Ursula K. Le Guin. Reprinted by arrangement with The Permissions Company, Inc., on behalf of Shambhala Publications Inc., Boston, MA. www.shambhala.com.

Poems by John Crook reprinted by kind permission of his family

Poem by Rupesh Shah reprinted by kind permission of the author

First published in 2014, 2017

by Jessica Kingsley Publishers

73 Collier Street

London N1 9BE, UK

and

400 Market Street, Suite 400

Philadelphia, PA 19106, USA

www.jkp.com

Copyright Peter Reason 2014, 2017

Foreword copyright Paul Evans 2014, 2017

Front cover image source: [iStockphoto/Shutterstock]. The cover image is for illustrative purposes only, and any person featuring is a model.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying, storing in any medium by electronic means or transmitting) without the written permission of the copyright owner except in accordance with the provisions of the law or under terms of a licence issued in the UK by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd. www.cla.co.uk or in overseas territories by the relevant reproduction rights organisation, for details see www.ifrro.org. Applications for the copyright owners written permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be addressed to the publisher.

Warning: The doing of an unauthorised act in relation to a copyright work may result in both a civil claim for damages and criminal prosecution.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN 9781784504618

Foreword

T he sea is terrifying. However bad things get they can always be worse at sea. Storms and crashing tides transform that liminal seaside edge we associate with pleasure into existential crisis. We landlubbers, who stand ashore and wonder about the sea and its wild mysteries, also wonder about the motivation of those who venture out in small crafts. The world of charts, chandlery and tides, of wrecks, weather lore and navigation, so embedded in the languages of these islands, has a poetry which can seem arcane and remote. The sea itself its bounty abused, its purity polluted is now a source of environmental anxiety and threat. And yet, the romance of the open sea, its roving freedoms, its wilderness, sloshes through our imaginations like the shared tribal memory of mariners.

Of all the voyaging the sea calls us to, those undertaken by lone sailors have a unique resonance: the Dark Age peregrini casting themselves into waves in tiny coracles to find God; shipwrecked mutineers drifting in the hope of finding an island paradise; round-the-world yachtswomen and men pitting themselves against overwhelming odds to find fame; explorers, adventurers, fugitives these are enduring tales because they travel beyond the far reaches of our own experience. Peter Reason has written his voyage not just as a sailors yarn but as a thoughtful, challenging, moving account of a pilgrimage into wilderness.

Confronted by Nature at its most elemental, the intensity of the experience, the quality of the reflection and the humanity of the writing turn a journey from the south coast of England to the western isles of Ireland into an exploration of what it is to be human in the wilderness. At a time of increasing anxiety and environmental crisis, Peter questions how we live with Nature. Do we turn our backs on its troubling enormity or do we answer Natures challenge: a wild call and a clear call that may not be denied, as John Masefield put it?

This is a timely book of new British nature writing finding its sea legs within ideas of pilgrimage, ecological journeying, liminality of place, and essential engagement of self with the wild. This voyage is an adventure; it is also a conversation with Nature we can join as crew and feel the spindrift in our faces and the wind in our sails.

Paul Evans, Wenlock, (a long way from the sea), January 2014

For my grandchildren Otto, Liberty, Nathaniel, Aidan

That their generation may find a way of living

in harmony with Earth and her creatures

Which my generation has so conspicuously failed to do

Contents

Chapter One

A Day in the Life

if we do not hear the voices of the trees, the birds, the animals, the fish, the mountains and the rivers, then we are in trouble That, I think, is what has happened to the human community in our times. We are talking to ourselves. We are not talking to the river, we are not listening to the river. We have broken the great conversation. By breaking the conversation we have shattered the universe. All these things that are happening now are consequences of this autism.

Thomas Berry, Befriending the Earth

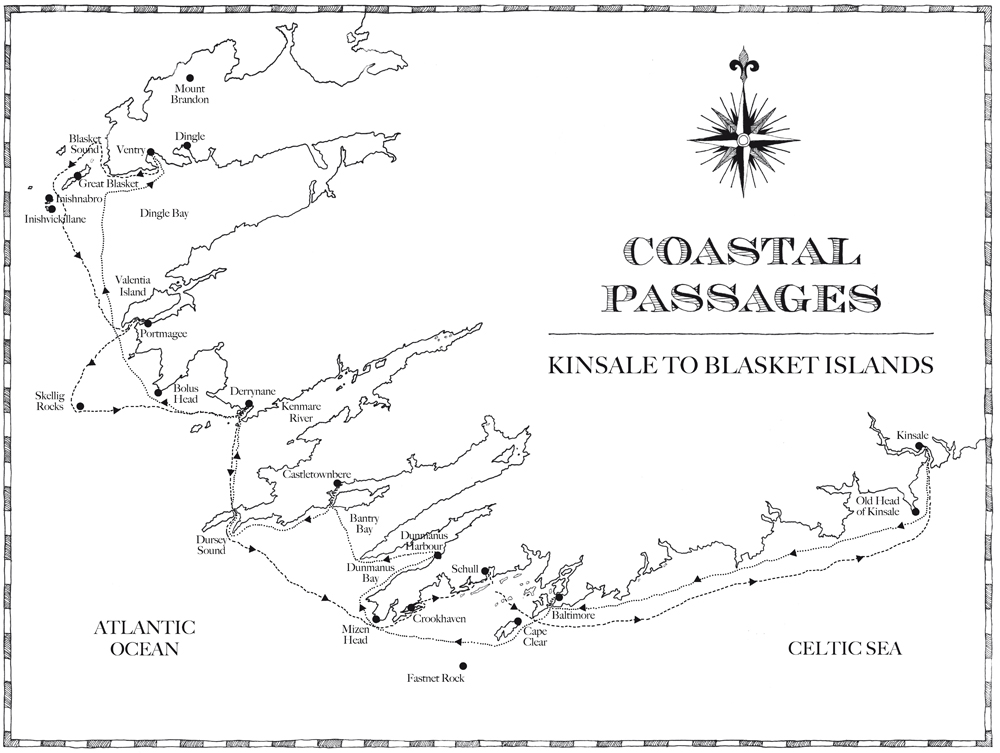

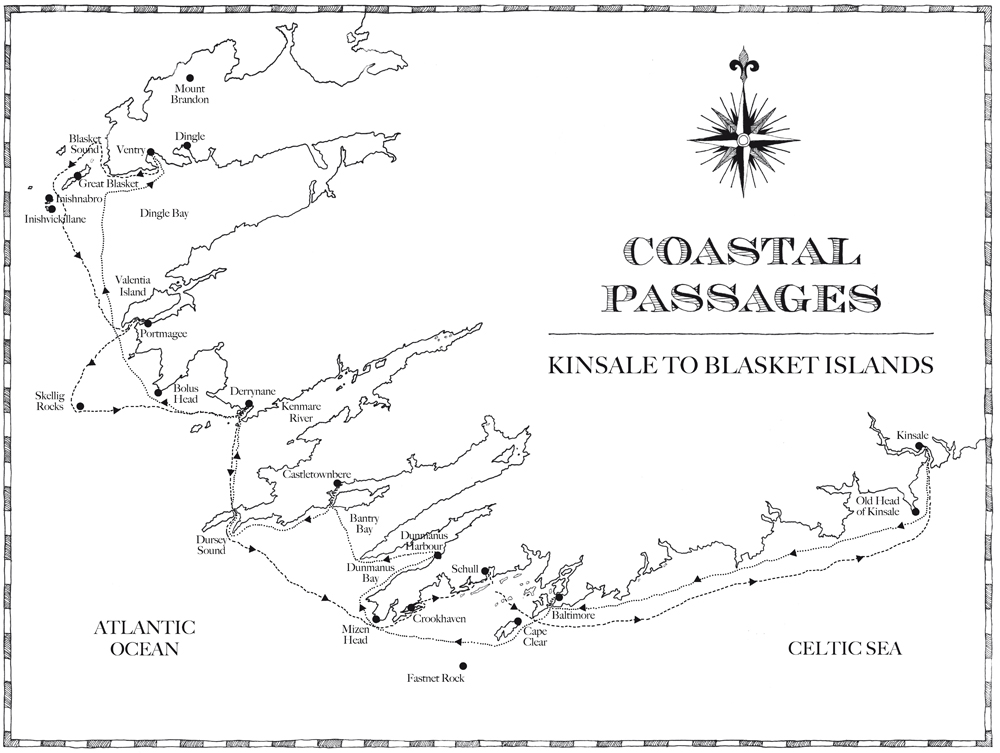

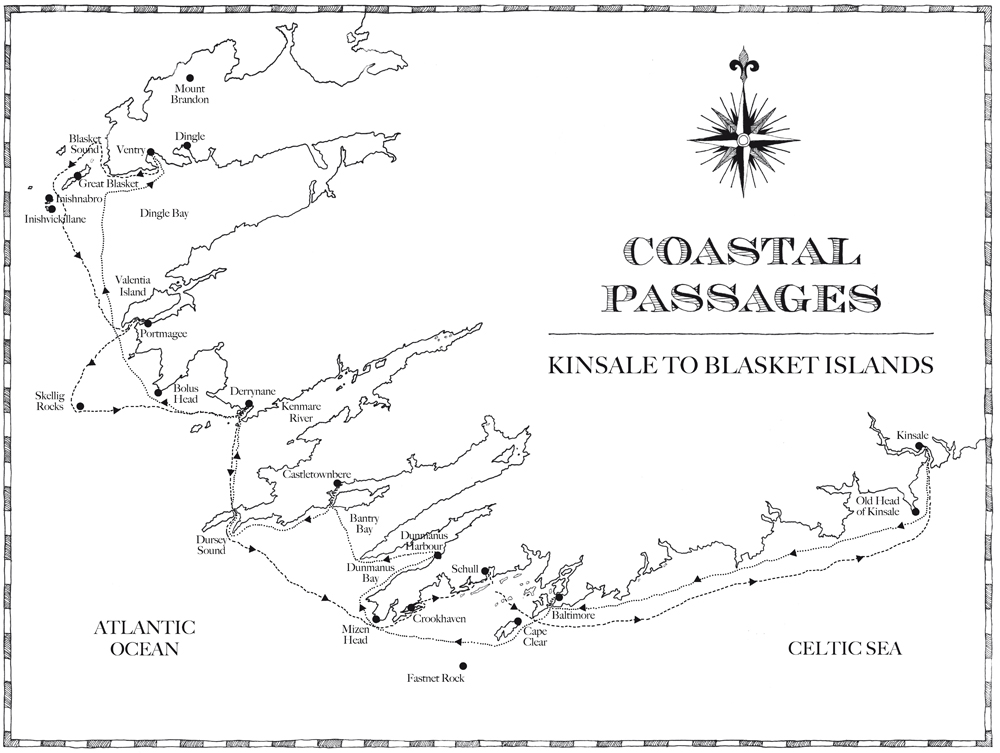

I woke early and for a few minutes lay in my bunk savouring the warmth of the duvet. As Coral swung to her anchor, the low April sun shone through her windows, dancing oval patches of light around the cabin. I watched them lazily, then shook myself properly awake and climbed out of my bunk, stretching my stiff back and legs. In the galley, I pumped water into the kettle, lit the gas ring and set water to boil for tea, before clambering up the companionway into the cockpit to look around. Derrynane Harbour is a pretty bay on the north side of the Kenmare River, just off the famous Ring of Kerry on the west coast of Ireland, where the land rises steeply from the sea to the mountains. I had arrived in harbour two days previously after sailing around the Blasket Islands and Skellig Rocks, watching gannets nesting and meeting a pod of dolphins along the way. The bay is enclosed by low-lying islands, rocky reefs and sandbars, well sheltered from all directions. That morning, little waves were breaking on a beach behind me, lines of white rolling up over yellow sand. Ahead of me, coastal hills rose gradually toward the steeper mountainside, a patchwork of stone walled fields scattered with white houses and trees more trees than one often sees on the west coast of Ireland. Above the fields, a clear line marked where the cultivated land stopped, and the scrubby brown of the mountains began.

It was still cold, the air clear and sharp too cold to be outside in pyjamas and bare feet. Soon I was shivering, but stayed out long enough to notice there was only a trace of movement in the water, scarcely breaking the reflection of moored boats and the surrounding rocks and hills. Hardly a drop of wind. I was disappointed, even a bit grumpy, that there was no sign of the northeasterlies forecast the previous evening I really wanted a good sail that day. Maybe the wind would arrive as the day woke up properly, as my wife Elizabeth likes to say.

Next page