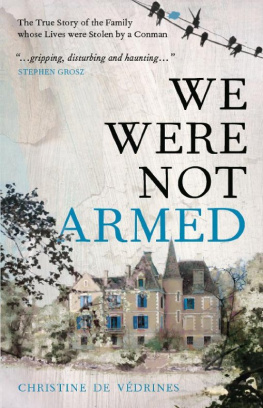

We Were Not Armed

PRAISE FOR

We Were Not Armed

The phrase folie a deux describes the situation in

which two people share a madness. We Were Not

Armed is the extraordinary account of a madness

that takes hold, over a decade, of three generations

of an entire family. Raw and undigested, Christine

de Vdrines compelling account of how her family

was destroyed by a confidence trickster is utterly

gripping, disturbing and haunting. Time and again,

I found myself thinking: is this a unique situation,

one that could only have happened at this moment

to these people, or is there something in all of

us that is vulnerable, that means we too could

succumb to this kind of madness?

Stephen Grosz,

author of The Examined Life

We Were Not Armed

By Christine de Vdrines

Translated by Angela Scholar

Appendix by Daniel Zagury

Published by Skyscraper Publications Limited

Talton Edge, Newbold on Stour,

Warwickshire CV37 8TR

www.skyscraperpublications.com

First published 2015

Copyright 2015 Christine de Vdrines

and family, Daniel Zagury

The authors rights are fully asserted. The right of

Christine de Vdrines and Daniel Zagury to be

identified as the authors of this work has been

asserted by them in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved; no part of this publication may be

reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted,

in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior

written permission of the publisher. Nor be circulated in

any form of binding or cover other than that in which

it is published and a similar condition including this

condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library.

ISBN-13: 978-0-9926270-5-8

ISBN: 978-0-9926270-3-4 (eBook)

Designed and typeset by

Chandler Book Design

Printed in the United Kingdom by

Latitude Press Ltd

To the memory of my parents

To the memory of my cousin Bernard

To my husband and my children

To my family

To my husbands family

To Bobby, to our friends, and to those

friends of our children who have helped us

and still support us today

To our lawyers

Consider what your own part is in the

disorder of which you complain.

Sigmund Freud

...whose nature is so far from doing harms

that he suspects none, on whose foolish

honesty my practices ride easy.

Edmund, in King Lear, Act 1, scene 2,

by William Shakespeare

Contents

Houses and People

Houses:

Martel, chteau, home of Mamie and country home of Charles-Henri and Christine

Bordeneuve, country home of Ghislaine, 300m from Martel Talade, close to Martel, home of Philippe

Fontenay-sous-Bois, location of Paris home of Ghislaine Pyla, location of Christines seaside apartment

Caudran, location of the Bordeaux home of Charles-Henri and Christine de Vdrines

People

Guillemette (Mamie) de Vdrines, matriarch of de Vdrines family

Her daughter Anne, died 1997, married to Bertrand Her son Philippe de Vdrines

Brigitte, Philippes partner

Frdric, Philippes son

Lucille, Philippes daughter

tienne, Philippes son

Laurence, Philippes daughter

Her daughter Ghislaine Marchand, ne de Vdrines

Jean Marchand, Ghislaines husband

Franois, Ghislaines son

Guillemette, Ghislaines daughter

Her son Charles-Henri de Vdrines, married to Christine

Christine de Vdrines, ne de Cornette de Laminire

Their son Guillaume

Their son Amaury

Their daughter Diane

Franoise, Christines sister

Jean-Michel, Franoises husband

Marie-Hlne Hessel, Christines friend since childhood

Thierry Tilly, conman

Matre Vincent David, mutual friend of Thierry Tilly and Ghislaine

Jacques Gonzalez, co-conspirator with Tilly

Matre Picotin, lawyer specialising in victims of cults and brainwashing

Introduction

This afternoon, in the peace and quiet of the empty kitchen after the last-minute preparations that precede the lunchtime rush, I have reached my decision. I know the thought processes by which I have arrived here. The decisive moment was the conversation I had yesterday, with my boss Bobby Robert Pouget de St-Victor. And now? It amazes me that after such a long time I should be taking an initiative on this scale and of this scope and all alone too.

Charles-Henri meets me at the door. He accompanies me to work every morning and comes to collect me again at the end of the day. There are reasons for this. Affection is one. But this does not explain everything. We walk home together. In the busy streets of Oxford the lights are coming on in the pubs, students rush by on bicycles, in noisy groups. We pass several old half-timbered houses, then we go through a district of blocks of flats pink, pale green, old and irregular, which soon give way to pretty little houses complete with tiny gardens, where bay windows project over perfectly tended lawns: the very image of the real world.

We make slow progress, because I limp badly, and my leg causes me pain. The passers-by we encounter pay no attention to this couple who walk with measured steps, and with a silent and somewhat detached air. They dont even glance at us. Were zombies. Each day we walk for almost an hour, going to and from work. We havent enough money to take a bus, let alone run a car. Ninety percent of our pay is regularly taken from us.

Little blocks of flats have now replaced the houses, and there are hardly any more gardens. Early spring in England is not kind. On this particular evening a sharp wind lashes our faces, until in the Cowley Road we reach a decrepit concrete block of flats. We still have to climb the sixty steps of a steep and narrow staircase. After which, I will fling myself down on to the sofa. I will close my eyes. Exhaustion will overcome me, I will try to sleep. Charles-Henri will suggest we have a bite to eat, and will heat up a tin of soup.

But on this particular evening, exhausted though I am, nervousness and impatience rack my whole body. I dont know this yet, but it is a renewal of life that is coursing through my veins. I must say nothing to Charles-Henri; he must suspect nothing. We go to bed early, he falls asleep immediately, and I remain for hours in the dark, not moving, waiting for daylight. At one point, I get up and stuff into my bag all the papers I will need, all those I have been able to save. Proof. Evidence. My story. Then I go back to bed, trembling for fear that he may have seen or even heard me. But no. He is asleep.

At six oclock, I get up, take a shower and dress as quickly as possible. Nothing in my behaviour or appearance must be different from usual: I pull on my old jacket, my denim skirt, a sweater worn through at the elbows, my flat shoes, which could do with re-soling. In any case, I have nothing else to put on. We set out, Charles-Henri and I, repeating our walk of the previous evening, but in the opposite direction. He leaves me in front of Bobbys kitchen and goes off to his own work as a gardener.

I should like to behave as though everything really were just as it always is. I should like to begin cleaning and cutting up the organic vegetables, as I do every morning. But there is no question of that today. Bobby gives me my entire months wages in cash. A car and a driver are waiting for me. Bobby embraces me, and wishes me luck. The car door slams shut. Throughout the whole journey to St. Pancras Station, I am incapable of uttering a single word; I am dumb with anxiety. The driver parks the car nearby, and we walk together towards the platform.

Next page