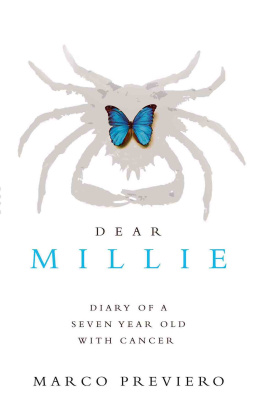

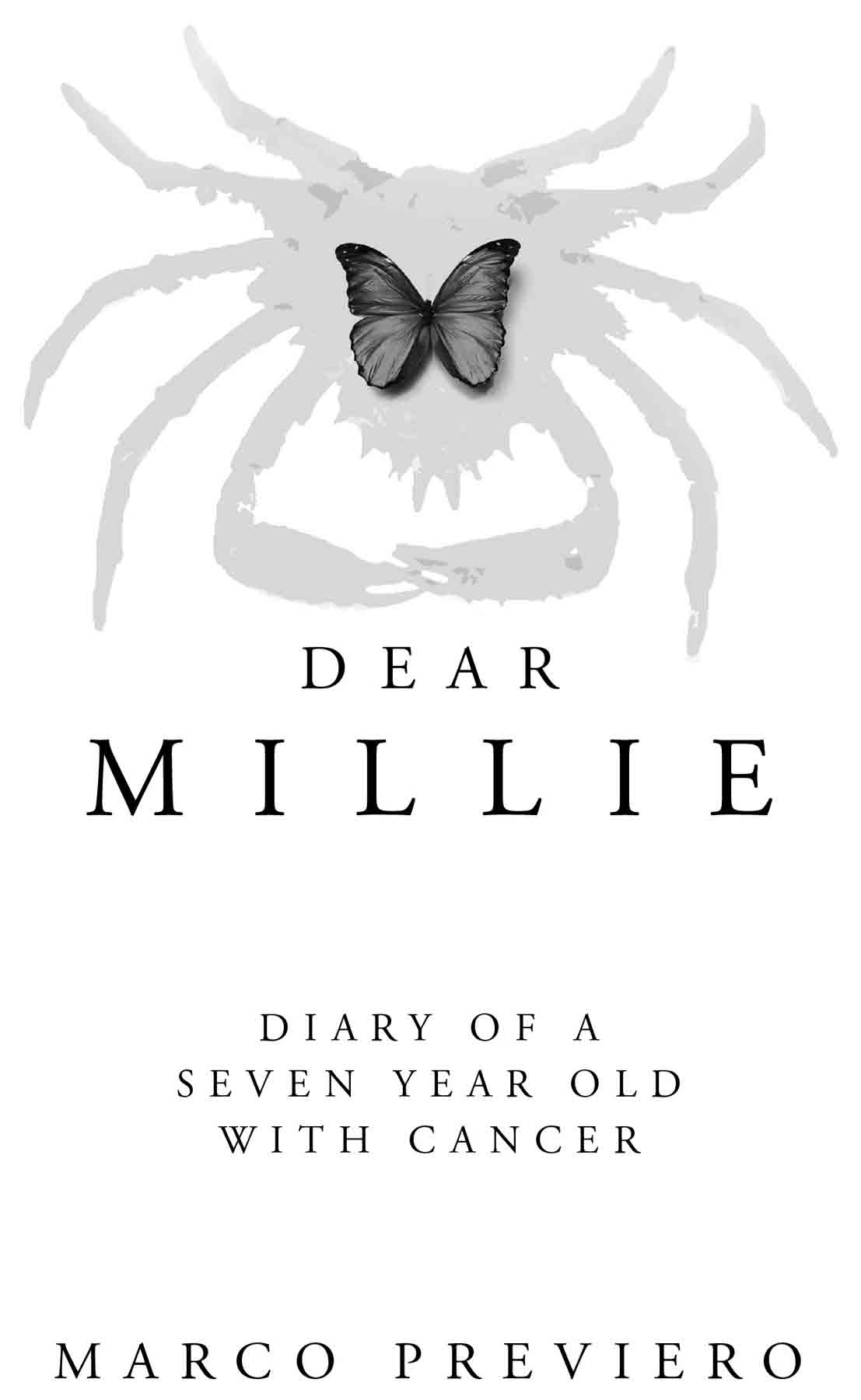

MARCO PREVIERO was born in Montpellier, France, in 1972. He moved to the UK in 1988 to finish his schooling and stayed. Having long accepted without too much remorse the gentle pleasures of an uneventful and ordinary life, he was woefully unprepared to guide and support his seven-year-old daughter through the vicious agony of cancer treatment when she was diagnosed with a malignant brain tumour in April 2013. He has been trying his best to be a good father ever since.

Copyright 2015 Marco Previero

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers.

Matador

9 Priory Business Park

Kibworth Beauchamp

Leicestershire LE8 0RX, UK

Tel: (+44) 116 279 2299

Fax: (+44) 116 279 2277

Email:

Web: www.troubador.co.uk/matador

ISBN 978-1784629-267

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Matador is an imprint of Troubador Publishing Ltd

To Millie, who has, despite her young age, guided me throughout this ordeal, and inspired me to keep going when hope was a currency I could not afford to use.

To Mr J Millies neurosurgeon whose judgment, decision-making and skills were the single most instrumental and contributory factors in saving Millies eyesight and, on the balance of probabilities, her life.

To the student nurses, nurses and senior nurses of Koala Ward (Great Ormond Street Hospital). In our darkest hours, you made all the difference.

Dear Millie is a true, factual narrative account of my daughters cancer treatment. As such, some names and identifying details have been changed to protect the privacy of those individuals who have asked to remain anonymous.

Chapter headings are extracts from Henry F. Careys translation of The Divine Comedy (Harvard Classics, Vol 20 PF Collier & Son Company 190914).

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Dear Millie,

I am writing you this letter in the hope that life has afforded you the opportunity to grow old enough to read it. Shortly after your seventh birthday you were diagnosed with a secreting germ cell tumour, a rare and malignant cancer of the brain, which initially manifested itself when you complained of fuzziness in your beautiful brown eyes on the morning of 5th April 2013. The fuzziness, I quickly established, turned out to be loss of vision in your right eye and near-blindness in your left one.

Within the next two days you had undergone your first eight-hour craniotomy (brain operation) to preserve the little vision you had left. Within four days, by now blind, you were diagnosed with cancer, and within a fortnight you had begun your first cycle of aggressive chemotherapy. Over the course of the six months that followed, you would undertake two further brain operations, three additional cycles of chemotherapy and thirty sessions of radiotherapy 4,000 miles away from home.

The events that unfolded during that year were the most traumatic, upsetting and painful events in your life, in my life, in your mothers life and in pretty much all of our familys lives combined. To keep my sanity, I started writing what was happening to us as a family, and what was happening to you as my daughter. In doing so, I wanted to preserve the detail, so easily forgotten, of what you had to go through, and the courage with which you did it, so that you could read your story at an age when you would understand how extraordinary you had been during that time.

If you are reading this letter and diary now, then you have lived to tell the tale: a tale of courage, of fortitude, of resilience, of pain, of destruction, and, ultimately, of rebirth.

When hope was a currency I could not afford to use, in places sunlight could not reach, you rescued me out of the dark hell that is cancer when it creeps slowly, unstoppable, towards a loved one; and one so young. And so I felt it was fitting that I should use one of the most famous epic poems, The Divine Comedy, to help me narrate the events that unfolded during 2013, with you, rather than Virgil, as my guide.

Hell (Inferno) describes perhaps the most violent period of your illness: the discovery of the tumour and your first brain operation. Fear, uncertainty and shock were the dominant themes. Would you regain your eyesight? Would you live long enough for the medical profession to attempt to cure this most destructive of diseases? Would you remain the Millie May we had grown to love so much?

In Purgatory (Purgatorio) you will read how chemotherapy affected you, and why you had to undertake two further brain operations. We knew by now what we were facing. We knew it could eventually end your life. Much doubt remained: would your cancer be sensitive to the wave of cytotoxic drugs that were going to be systematically injected directly into your bloodstream over four months? How successful would the neurosurgeon be in removing the whole of the cancerous lump that was set deep within your brain? How would it affect some of the vital areas responsible for pumping out hormones essential for coping with day-to-day life?

And, finally, Heaven (Paradiso), which saw us move lock, stock and barrel 4,000 miles away from home, with your brother and sister in tow so you could receive one of the most advanced radiotherapy treatments in the world over the course of nine weeks: proton beam. Treatment that would nonetheless cause some permanent damage to healthy brain matter and affect you cognitively; treatment that would alter your ability to produce your own growth hormones; treatment that could, in time, cause further malignancies in your brain

What choice did we have? What alternative courses of action were available? Cancer kills and you had it. In attempting to cure it, we needed to provide the most beneficial treatment with the lowest risk. Most beneficial treatment and risk were both relative and contextual. There was no black and white in that game of life and death. We knew that in curing cancer we were going to cause irreparable damage that would alter your quality of life in a way we could not easily predict, and make you significantly worse before possibly making you better because with the alternative there simply was no quality of life.

I hope we managed to weather the storm that descended with such brutal force into our lives, that 5th April 2013. I hope your mother and I were up to the task; we certainly tried our best. I hope you will look back at this period with a deep sense of pride and achievement in how you handled it all with the minimum of fuss. I hope you will realise how proud your mother and I are of you, then and now, and every minute in between. And, finally, I hope you will always remember the love of a father who never doubted his commitment to get you out of the grips of cancer and who will always carry your heart in his heart. This is your story.

Next page